Given the continuing public mania over dinosaurs, and recent important discoveries of yet more exquisite specimens of feathered theropod dinosaurs discovered in countries far away from the U.S. (here and here), it is sometimes easy to forget what has long been known about these animals, and right here in my own “backyard” (globally speaking).

Need to see some of the best dinosaur tracks in the world, and you live in the southeastern U.S.? Guess what: you can seen them in Glen Rose, Texas. Not China, Mongolia, Canada, Utah, or some other far-off land inhabited by strange people with unusual customs, but Texas. Saddle up! (Photograph by Michael Blair, taken in Dinosaur Valley State Park, Texas.)

Need to see some of the best dinosaur tracks in the world, and you live in the southeastern U.S.? Guess what: you can seen them in Glen Rose, Texas. Not China, Mongolia, Canada, Utah, or some other far-off land inhabited by strange people with unusual customs, but Texas. Saddle up! (Photograph by Michael Blair, taken in Dinosaur Valley State Park, Texas.)

So on July 22, just to jog my memory a bit, I flew from Atlanta, Georgia to the Dallas-Ft. Worth (Texas) airport, and only a few hours later was gazing upon dinosaur tracks accompanied by the burrows of invertebrate animals, both trace fossils having been made more than 100 million years ago. It was a fitting welcome to Glen Rose, Texas, a place famous for its dinosaur trace fossils since the 1930s, and where dinosaurs were an integral part of its culture long before it was cool, hip, and contemporary elsewhere.

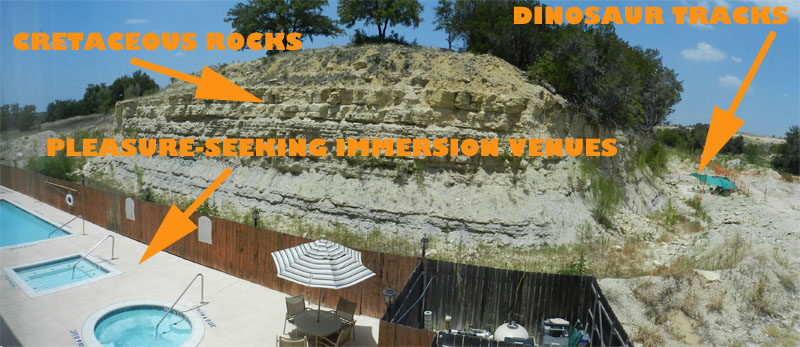

In Glen Rose, Texas, the dinosaur tracks are so abundant, you can choose whether to see these just outside of your hotel room, or go to the hotel jacuzzi and pool. Naturally, I chose both. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Glen Rose, Texas.)

In Glen Rose, Texas, the dinosaur tracks are so abundant, you can choose whether to see these just outside of your hotel room, or go to the hotel jacuzzi and pool. Naturally, I chose both. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Glen Rose, Texas.)

So just how did I end up in Glen Rose, Texas, looking at Cretaceous dinosaur tracks and invertebrate burrows? I was lucky enough to be there as an invited participant in an expedition sponsored by the National Geographic Society. I say “lucky” because luck was certainly a part of it, a fortuitous connection made through my writing a book about the modern traces of the Georgia coast. James (Jim) Farlow, a paleontologist at Indiana-Purdue University Fort Wayne (IPFW) and an associate editor with Indiana University Press, reviewed the first draft of my book, but he was also in charge of this dinosaur-track expedition to Glen Rose. Evidently he was impressed enough about what I knew about invertebrate burrows (or at least what I wrote about them) that he considered me as a possible member for his team of scientists, field assistants, and teachers on this expedition.

Dr. Jim Farlow, the world expert on the Glen Rose dinosaur tracks, having a reflective moment at Dinosaur Valley State Park near Glen Rose, Texas. What’s with the broom? He and other people in the expedition used these to sweep river sediment out of dinosaur tracks submerged in the river. In 100° F (38° C) temperatures. On the other hand, I just described invertebrate trace fossils, which was more of a job, not work. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Dinosaur Valley State Park, Texas.)

Dr. Jim Farlow, the world expert on the Glen Rose dinosaur tracks, having a reflective moment at Dinosaur Valley State Park near Glen Rose, Texas. What’s with the broom? He and other people in the expedition used these to sweep river sediment out of dinosaur tracks submerged in the river. In 100° F (38° C) temperatures. On the other hand, I just described invertebrate trace fossils, which was more of a job, not work. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Dinosaur Valley State Park, Texas.)

Thus when Jim asked me last fall if I would be interested in joining them to describe and interpret the Cretaceous invertebrate burrows that occur with the dinosaur tracks there, I jumped at the opportunity. The Glen Rose dinosaur tracksites, most of which crop out in the Paluxy River bed in Dinosaur Valley State Park, are world famous for their quantity and quality, and they connect with an important part of the history of dinosaur studies. Going there, experiencing these tracks for myself, and better understanding their paleoecological and geological context would be of great benefit to me, my students, and of course, you, gentle readers.

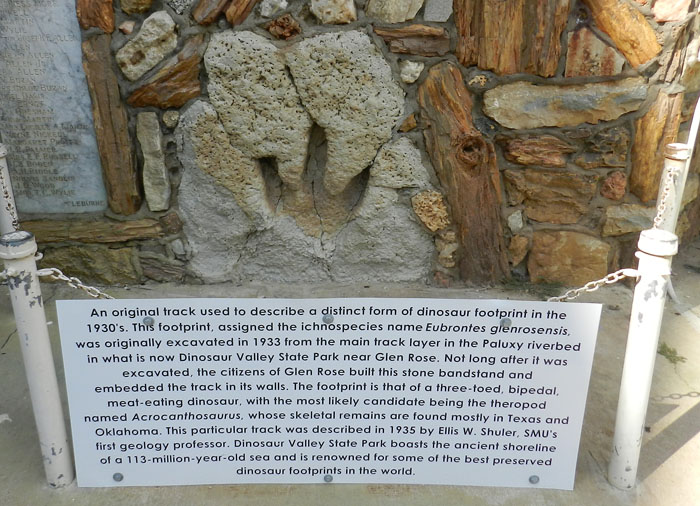

Just to back up a bit, and clarify for anyone who doesn’t know why these tracks are so darned important, here’s a brief background. In November 1938, Roland T. Bird, an employee of the American Museum of Natural History and a field assistant to flamboyant paleontologist Barnum Brown (the guy who named Tyrannosaurus rex), saw large, isolated limestone slabs with theropod dinosaur tracks in a Native American trading post in Gallup, New Mexico. Upon inquiring about the origin of these tracks, Bird was told they came from Glen Rose, Texas. So he set out in his Buick for Glen Rose to see for himself whether these tracks were real or not, and whether there were any more to see in the rocks around Glen Rose. The theropod track set in the town bandstand – pictured below – was one of the first sites that greeted him, and Glen Rose locals told him about the tracks in the Paluxy River.

Glen Rose, Texas, the only place in the world where the town bandstand has an Early Cretaceous theropod dinosaur track on display. Wish I could also tell you about all of those little holes in the rock with that track, but I can’t right now. Nonetheless, rumor has it they are burrows made by small, marine invertebrates that lived at the same time as the dinosaurs. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Glen Rose, Texas.)

Glen Rose, Texas, the only place in the world where the town bandstand has an Early Cretaceous theropod dinosaur track on display. Wish I could also tell you about all of those little holes in the rock with that track, but I can’t right now. Nonetheless, rumor has it they are burrows made by small, marine invertebrates that lived at the same time as the dinosaurs. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Glen Rose, Texas.)

Bird had hit the jackpot, the motherlode, the bonanza, the surfeit, the, well, you get the point. Not only did the Paluxy River outcrops contain hundreds of theropod dinosaur tracks – many as continuous trackways – but also the first known evidence of sauropod dinosaur tracks.

A couple of beautifully preserved theropod tracks under shallow water in the Paluxy River. Note that the track at the bottom also has a partial metatarsal (“heel”) impression, and look closely for the digit I (“thumb”) imprint on the right. Scale is about 20 cm (8 in) long. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Dinosaur Valley State Park, Texas.)

A couple of beautifully preserved theropod tracks under shallow water in the Paluxy River. Note that the track at the bottom also has a partial metatarsal (“heel”) impression, and look closely for the digit I (“thumb”) imprint on the right. Scale is about 20 cm (8 in) long. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Dinosaur Valley State Park, Texas.)

Funny how those “potholes” in the limestone bedrock of the Paluxy River have oblong outlines and form regular alternating patterns, isn’t it? Well, them ain’t no potholes, y’all. They’re sauropod tracks, and were among the hundreds recognized as the first know =n such tracks from the geologic record. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Dinosaur Valley State Park, Texas.)

Funny how those “potholes” in the limestone bedrock of the Paluxy River have oblong outlines and form regular alternating patterns, isn’t it? Well, them ain’t no potholes, y’all. They’re sauropod tracks, and were among the hundreds recognized as the first know =n such tracks from the geologic record. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Dinosaur Valley State Park, Texas.)

The discovery of sauropod tracks was as huge as the tracks. Up until then, sauropods were assumed to have been so large that they could not support their weights on land and spent most of their time in water bodies. These tracks said otherwise, that these sauropods were walking along mudflats along with the theropods. In short, the trace fossil evidence contradicted the assumed story about how these massive animals moved. After all, trace fossils are direct records of animal behavior, and if interpreted correctly, can tell paleontologists more about what an animal was doing on a given day than any amount of shells, bones, and yes, even feathers.

Sauropod tracks from the main tracksite in Dinosaur Valley State Park, Texas. The sauropod was moving away in this view, and the trackway pattern is a typical diagonal-walking one, right-left-right. In parts of this trackway, both the manus (front foot) and pes) rear foot registered, something Bird noticed in 1938, his observation accompanied by more than a little bit of excitement. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Dinosaur Valley State Park, Texas.)

Sauropod tracks from the main tracksite in Dinosaur Valley State Park, Texas. The sauropod was moving away in this view, and the trackway pattern is a typical diagonal-walking one, right-left-right. In parts of this trackway, both the manus (front foot) and pes) rear foot registered, something Bird noticed in 1938, his observation accompanied by more than a little bit of excitement. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Dinosaur Valley State Park, Texas.)

The details preserved in these sauropod tracks are also astounding. Most sauropod tracks I have seen elsewhere, in Jurassic and Cretaceous rocks of the American West, Europe, and Western Australia, are only evident as large, rounded depressions that you would only know are tracks because they form diagonal-walking patterns. In contrast, the Glen Rose tracks include all five toe and claw impressions on the rear feet (pes) and full outlines of the front feet (manus). The original calcium-carbonate mud in the shoreline environments where the sauropods walked, similar to mudflats I’ve seen in the modern-day Bahamas, is what made this exquisite preservation possible. The mud had to be firm enough to preserve these specific details of the sauropods’ feet, but not so soft that the mud would collapse into the tracks after the sauropods extracted their feet.

Beautifully preserved tracks, manus (top) and pes (bottom). Note the five toe impressions in the pes, which along with its size confirms that these were made by a large sauropod. Meter stick for scale. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Dinosaur Valley State Park, Texas.)

Beautifully preserved tracks, manus (top) and pes (bottom). Note the five toe impressions in the pes, which along with its size confirms that these were made by a large sauropod. Meter stick for scale. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Dinosaur Valley State Park, Texas.)

One sauropod trackway, preserved with a theropod trackway paralleling and intersecting it, was actually quarried out of the river and taken to the American Museum. Once there, its pieces stay disassembled for years, before Bird helped with putting the puzzle pieces back together so that it could be used as part of a display there.

Archival video footage of Roland Bird and his field crew working on the dinosaur tracks in the Paluxy River near Glen Rose, Texas. More about this tracksite and its role in the history of dinosaur paleontology is ably conveyed by Brian Switek here.

Photos at the visitor’s center at Dinosaur Valley State Park, showing the sequence of clearing (left) and extraction (right) of the limestone bed containing the theropod and sauropod dinosaur tracks. (Photographs taken of the photographs, then enhanced, cropped, and placed side-by-side by Anthony Martin.)

Photos at the visitor’s center at Dinosaur Valley State Park, showing the sequence of clearing (left) and extraction (right) of the limestone bed containing the theropod and sauropod dinosaur tracks. (Photographs taken of the photographs, then enhanced, cropped, and placed side-by-side by Anthony Martin.)

A lasting trace today of Roland Bird and his field helpers from the 1940s, in which they took out a sauropod and theropod trackway from this place and transported it to New York City. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Dinosaur Valley State Park, Texas.)

A lasting trace today of Roland Bird and his field helpers from the 1940s, in which they took out a sauropod and theropod trackway from this place and transported it to New York City. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Dinosaur Valley State Park, Texas.)

Other than some of the best-preserved Early Cretaceous dinosaur tracks in the world, one other claim to fame for the Glen Rose area, and not such a proud one, is its attraction to evolution deniers, a few charlatans who used the tracks to promote what might be mildly termed as cockamamie ideas. You see, Glen Rose is also the site of the infamous “man tracks.” These tracks are preservational variants of theropod tracks that – through a combination of the theropods sinking into mud more than 100 million years ago and present-day erosion of the tracks in the Paluxy River – prompted some people to claim these were the tracks of biblical giants who were also contemporaries of the dinosaurs. (Perhaps this is as good of a time as any to start humming the theme music for The Flintstones.)

Rare documentary footage of humans and dinosaurs interacting with one another during the Early Cretaceous Period, or the Late Jurassic Period. Whatever. Note the inclusion of other seemingly anachronistic mammals, too, such as the saber-toothed felid Smilodon. Perhaps this footage could be included in the curriculum of some U.S. public schools, providing a formidable counter to the views of 75 Nobel laureate scientists. Then we’ll let the kids decide which is right.

I will not waste any further electrons or other forms of energy by continuing to flog this already thoroughly discredited notion, but instead will direct anyone interested to a thorough accounting of this debacle to some actual scholarship here, summarizing original research by Glen Kuban and others in the 1980s through now that have laid to rest such spurious notions. Speaking of Mr. Kuban, I was delighted to meet him for the first time during while in Glen Rose (we had corresponded a few times years ago). I was even more gratified to spend a few hours in the field with him, discussing the genuinely spectacular trace fossils there in Dinosaur Valley State Park with these directly in front of us. Again, I’m a lucky guy.

The expedition was scheduled in Glen Rose for three weeks during late July through early August, but with so many commitments for this summer, I could only carve out a week for myself there, from July 22-29. Fortunately, this was enough time for me to accomplish what was needed to do, while also having fun getting to know the rest of the expedition crew – teachers, artists, videographers, laborers – and enjoying wonderful discussions (and debates) with colleagues in the field. The people of Glen Rose were also exceedingly welcoming and accommodating to us: we felt like rock stars (get it – “rock”?), and were feted by local folks three nights in a row during the week I was there. Many thanks to these Glen Rose for the the exceptional hospitality they extended to our merry band of paleontologists, geologists, river sweepers, or what have you.

You can’t see it, but I’m standing in a sauropod dinosaur track, which is a little deeper than the rest of the river bed. You also can’t see the invertebrate burrows that are in the limestone bedrock, which is fine, because I can’t show them to you yet anyway. But be patient: you’ll learn about them some day. (Photograph by Martha Goings, taken in Dinosaur Valley State Park, Texas.)

You can’t see it, but I’m standing in a sauropod dinosaur track, which is a little deeper than the rest of the river bed. You also can’t see the invertebrate burrows that are in the limestone bedrock, which is fine, because I can’t show them to you yet anyway. But be patient: you’ll learn about them some day. (Photograph by Martha Goings, taken in Dinosaur Valley State Park, Texas.)

I can’t yet say much more about what I did during that week, as all participants signed an agreement that National Geographic has exclusive rights to research-related information, photos, and video unless approved by them. But if you’re a little curious about the daily happenings of the expedition (which just ended last week), Ray Gildner maintained a blog that succinctly touched on all of the highlights, Glen Rose Dinosaur Track Expedition 2012.

Still, I can say, with great satisfaction, that I did successfully describe and interpret invertebrate trace fossils that were in the same rocks as the dinosaur tracks. Hopefully my colleagues and I will have figured out how these burrows related to environments inhabited by the dinosaurs that walked through what we now call Texas.

All in all, my lone week in the Lone Star State was a marvelously edifying and educational experience, one I’ll be happy to share with many future generations of students and all those interested in learning about the not-so-distant geologic past of the southeastern U.S.

Group photo from the Glen Rose Dinosaur Track Expedition 2012. Names of all participants can be found here, but in the meantime, just sit back and admire those Dinosaur World t-shirts everyone is wearing. (Photograph by James Whitcraft or Ray Gildner: they can fight over who actually took it. Although, the automatic timer on his camera took the photo, so maybe it should get credit instead.)

Group photo from the Glen Rose Dinosaur Track Expedition 2012. Names of all participants can be found here, but in the meantime, just sit back and admire those Dinosaur World t-shirts everyone is wearing. (Photograph by James Whitcraft or Ray Gildner: they can fight over who actually took it. Although, the automatic timer on his camera took the photo, so maybe it should get credit instead.)

Further Reading

Bird, R.T. 1985. Bones for Barnum Brown: Adventures of a Dinosaur Hunter. Texas Christian University Ft. Worth, Texas: 225 p.

Farlow, J.O. 1993. The Dinosaurs of Dinosaur Valley State Park. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Austin, Texas: 30 p.

Jasinski, L.E. 2008. Dinosaur Highway: A History of Dinosaur Valley State Park. Texas Christian University, Ft. Worth, Texas: 212 p.

Kuban, G.J. 1989. Elongate Dinosaur Tracks. In Gillette, David D., and Martin G. Lockley (editors), Dinosaur Tracks and Traces, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K.: 57-72.

Pemberton, S.G., Gingras, M.K., and MacEachern, J.A. 2007. Edward Hitchcock and Roland Bird: Titans of Vertebrate Ichnology in North America. In Miller, William, III (editor), Trace Fossils: Concepts, Problems, Prospects. Elsevier, Amsterdam: 32-51.

There’s a nice paper on the bandstand track’s digitizing in PE. Open access, and free of page charges, too (had to be mentioned):

http://palaeo-electronica.org/2010_3/226/index.html

Hi Heinrich,

Thanks for your comment. Yes, I had seen that paper, and it was a thrill to see that track in the bandstand after having read it before coming out to Texas this past summer! And of course, I agree completely that open-access, free-of-page-charge papers need to be publicized as much as possible, so thank you for sharing the link with everyone reading this blog.

Cheers/Prost,

Tony