When learning about the natural sciences, there comes a time when just reading and talking about your topics in the confines of a classroom just doesn’t cut it. This semester, we had reached that point in a class I’m teaching at Emory University (Barrier Islands), in which we all needed a serious reality check to boost our learning. So how about a week-long field trip, and to some of the most scientifically famous of all barrier islands, which are on the coast of Georgia?

Last Friday, March 8, our excursion officially began with a long drive from the Emory campus in Atlanta, Georgia to St. Marys, Georgia. Fortunately, Saturday morning was much easier, only requiring that we walk across the street, step onto a ferry, and ride for 45 minutes to Cumberland Island. Cumberland was our first island of the trip, and the southernmost of the Georgia barrier islands. I have written about other topics there, including the feral horses that leave their mark on island ecosystems, the tracks of wild turkeys, and those marvelous little bivalves, coquina clams.

So rather than my usual loquacious ramblings, punctuated by whimsical asides, this blog post and others later this week will be more photo-centered and accompanied by mercifully brief captions. This approach is not only a practical necessity for proper time management while teaching full-time through the week, but also is meant to give a sense of the daily discoveries that can happen through place-based learning on the Georgia coast. I hope you learn with us, however vicariously.

After a 45-minute ferry ride to Cumberland Island, the students received a different sort of lecture when naturalist extraordinaire Carol Ruckdeschel – who is writing a book about the natural history of Cumberland Island – met with them and gave them a brilliant overview of the island ecology. She mostly talked with the students about the effects of feral animals on the island, then spent another hour with us in the maritime forest and through the back-dune meadows. It was a real treat for the students and me, and a great way to start the field trip.

After a 45-minute ferry ride to Cumberland Island, the students received a different sort of lecture when naturalist extraordinaire Carol Ruckdeschel – who is writing a book about the natural history of Cumberland Island – met with them and gave them a brilliant overview of the island ecology. She mostly talked with the students about the effects of feral animals on the island, then spent another hour with us in the maritime forest and through the back-dune meadows. It was a real treat for the students and me, and a great way to start the field trip.

A leaf-cutter bee trace! Despite my writing about these and illustrating them in my book, these distinctive incisions were the first I can recall seeing on the Georgia barrier islands. These traces were abundantly represented in the leaves of a red bay tree we spotted along a trail through the maritime forest, making for a great impromptu natural history lesson for the students.

A leaf-cutter bee trace! Despite my writing about these and illustrating them in my book, these distinctive incisions were the first I can recall seeing on the Georgia barrier islands. These traces were abundantly represented in the leaves of a red bay tree we spotted along a trail through the maritime forest, making for a great impromptu natural history lesson for the students.

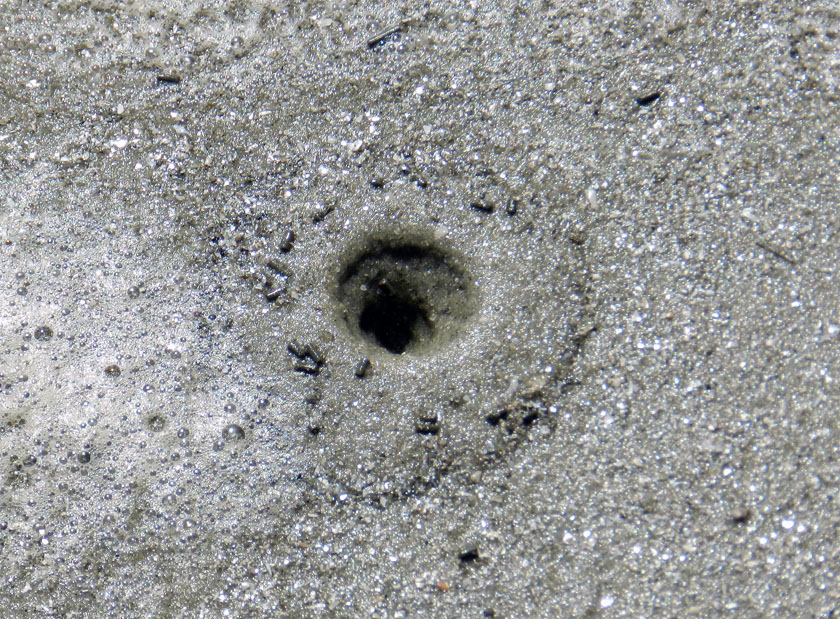

A freshly erupted ghost shrimp burrow on the beach at Cumberland, in which the students were lucky enough to witness the forceful ejection of muddy fecal pellets by the shrimp from the top of its burrow. I mean, really: explain to me how the life of an ichnologist-educator can get any better than that?

A freshly erupted ghost shrimp burrow on the beach at Cumberland, in which the students were lucky enough to witness the forceful ejection of muddy fecal pellets by the shrimp from the top of its burrow. I mean, really: explain to me how the life of an ichnologist-educator can get any better than that?

The fine tradition a field lunch, made even more fine by the addition of fine quart sand to our meals, freely delivered by a brisk sea breeze. Did the sand leave any microwear marks on our teeth? I certainly hope so.

The fine tradition a field lunch, made even more fine by the addition of fine quart sand to our meals, freely delivered by a brisk sea breeze. Did the sand leave any microwear marks on our teeth? I certainly hope so.

A student is delighted to test my ichnologically based method for finding buried whelks underneath beach sands, and find out that it is indeed correct. (Was there any doubt?) Here she is proudly holding a live knobbed whelk, which I can assure you she promptly placed back into the water once its photo shoot was finished for the day.

A student is delighted to test my ichnologically based method for finding buried whelks underneath beach sands, and find out that it is indeed correct. (Was there any doubt?) Here she is proudly holding a live knobbed whelk, which I can assure you she promptly placed back into the water once its photo shoot was finished for the day.

Just to join in the fun, other students decided my “buried whelk prospecting” method required further testing. Let’s just say this student did not disprove the hypothesis, but rather seemed to confirm it, and doubly so. It’s almost as if ichnology is a real science! (Yes, these whelks went back into the water, too.)

Just to join in the fun, other students decided my “buried whelk prospecting” method required further testing. Let’s just say this student did not disprove the hypothesis, but rather seemed to confirm it, and doubly so. It’s almost as if ichnology is a real science! (Yes, these whelks went back into the water, too.)

OK, enough about marine predatory gastropods (for now). How about some of the largest horseshoe crabs (limulids) in the world? We found a large deposit of their carapaces above the high-tide mark, some of which were probably molts, but others recently dead. Sadly, though, we did not see any of their traces. Bodies only do so much for me.

OK, enough about marine predatory gastropods (for now). How about some of the largest horseshoe crabs (limulids) in the world? We found a large deposit of their carapaces above the high-tide mark, some of which were probably molts, but others recently dead. Sadly, though, we did not see any of their traces. Bodies only do so much for me.

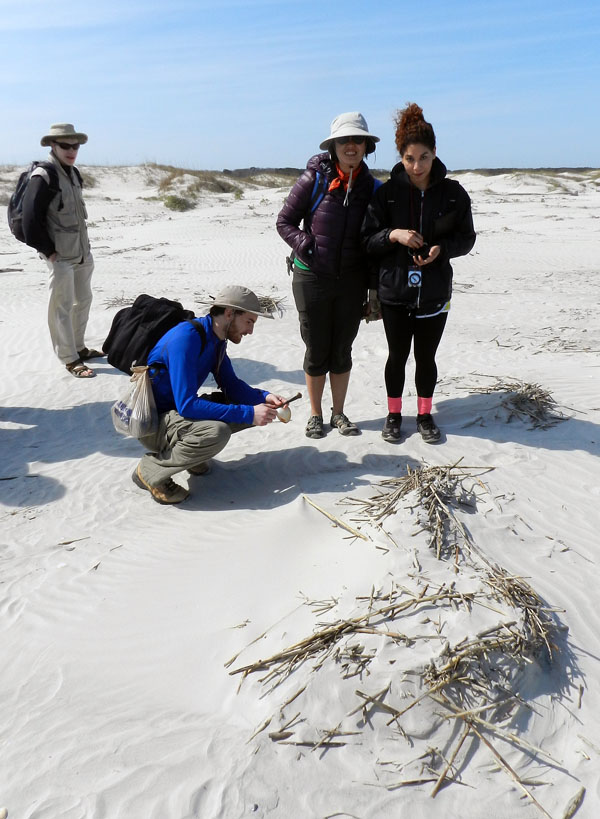

Where do dunes come from? Well, a mother and father dune love each other very much… No wait, wrong story. What happens is that dead cordgrass from the salt marshes washes up onto the beach, where it starts slowing down wind-blown sand enough that it accumulates. Now it just needs some wind-blown seeds of sea oats and other plants to start colonizing it, and next thing you know, dune. Dude.

Where do dunes come from? Well, a mother and father dune love each other very much… No wait, wrong story. What happens is that dead cordgrass from the salt marshes washes up onto the beach, where it starts slowing down wind-blown sand enough that it accumulates. Now it just needs some wind-blown seeds of sea oats and other plants to start colonizing it, and next thing you know, dune. Dude.

Ah, a geological tradition in action: comparing actual sand from a real outdoor environment to the sand categories on a handy grain-size chart, and using a hand lens. It’s enough to bring a tear to the eyes of this geo-educator. Or maybe that was just the wind-blown sand.

Ah, a geological tradition in action: comparing actual sand from a real outdoor environment to the sand categories on a handy grain-size chart, and using a hand lens. It’s enough to bring a tear to the eyes of this geo-educator. Or maybe that was just the wind-blown sand.

Finally, something that really matters, like ichnology! This is a three-for-one special, too: sanderling feces (left), tracks, and regurgitants (right), the last of these also known as cough pellets. Looks like it had coquina and dwarf surf clams for breakfast.

Finally, something that really matters, like ichnology! This is a three-for-one special, too: sanderling feces (left), tracks, and regurgitants (right), the last of these also known as cough pellets. Looks like it had coquina and dwarf surf clams for breakfast.

Wow, more shorebird traces! The tracks are from a loafing royal tern, and it clearly needed to get a load off its mind before moving on with the rest of its day.

Wow, more shorebird traces! The tracks are from a loafing royal tern, and it clearly needed to get a load off its mind before moving on with the rest of its day.

Tired of shorebird traces? How about a modern terrestrial theropod? Wild turkey tracks in the back-dune meadows of Cumberland were a happy find, leading to my grilling the students with the seemingly simple question, “What bird made this?” They did not do well on this, but hey, it was the first day, and at least no one said “robin” or “ostrich.”

Tired of shorebird traces? How about a modern terrestrial theropod? Wild turkey tracks in the back-dune meadows of Cumberland were a happy find, leading to my grilling the students with the seemingly simple question, “What bird made this?” They did not do well on this, but hey, it was the first day, and at least no one said “robin” or “ostrich.”

Did somebody say “doodlebug?” This long, meandering, and collapsed tunnel of an ant lion (a larval neuropteran, or lacwing) tells us that this insect was looking for prey in all the wrong places.

Did somebody say “doodlebug?” This long, meandering, and collapsed tunnel of an ant lion (a larval neuropteran, or lacwing) tells us that this insect was looking for prey in all the wrong places.

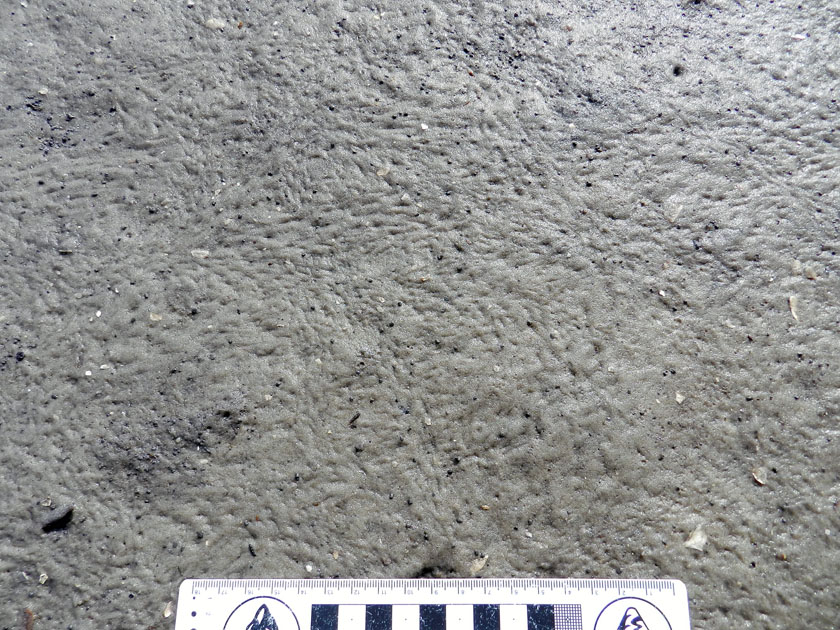

Behold, tracks that bespeak of great, thundering herds of sand-fiddler crabs that used to roam the sand flats above the salt marsh. Where have they gone, and will they ever come back? Who knows where the males might be waving their mighty claws? Do the female fiddler crabs suffer from big-claw envy, or are they enlightened enough to reject cheliped-based hierarchies imposed upon them by fiddler-crab society? All good questions, deserving answers, none of which make any sense.

Behold, tracks that bespeak of great, thundering herds of sand-fiddler crabs that used to roam the sand flats above the salt marsh. Where have they gone, and will they ever come back? Who knows where the males might be waving their mighty claws? Do the female fiddler crabs suffer from big-claw envy, or are they enlightened enough to reject cheliped-based hierarchies imposed upon them by fiddler-crab society? All good questions, deserving answers, none of which make any sense.

Yes, that’s right, feral horses are really bad for salt marshes. Between overgrazing and trampling, they aren’t exactly what anyone could call “eco-friendly.” My students had heard me say this repeatedly throughout the semester, and Carol Ruckdeschel said the same thing earlier in the day. But then there’s seeing it for themselves, another type of learning altogether.

Yes, that’s right, feral horses are really bad for salt marshes. Between overgrazing and trampling, they aren’t exactly what anyone could call “eco-friendly.” My students had heard me say this repeatedly throughout the semester, and Carol Ruckdeschel said the same thing earlier in the day. But then there’s seeing it for themselves, another type of learning altogether.

And the day ended with beautiful ripple marks, beckoning from the sandflat below the boardwalk on our trip back onto the ferry. Even this ichnologist can appreciate the aesthetic appeal of gorgeous physical sedimentary structures.

And the day ended with beautiful ripple marks, beckoning from the sandflat below the boardwalk on our trip back onto the ferry. Even this ichnologist can appreciate the aesthetic appeal of gorgeous physical sedimentary structures.

What’s the next island? Jekyll, which is just north of Cumberland along the Georgia coast, visited yesterday. Stay tuned, and look for those photos soon.