Among my favorite tracemakers of the Georgia barrier islands are birds, a fondness inspired by their great variety (more than 200 species), numbers, and diverse behaviors. But if pressed to name my absolute favorite types of bird traces, I would not hesitate to say “flying tracks.”

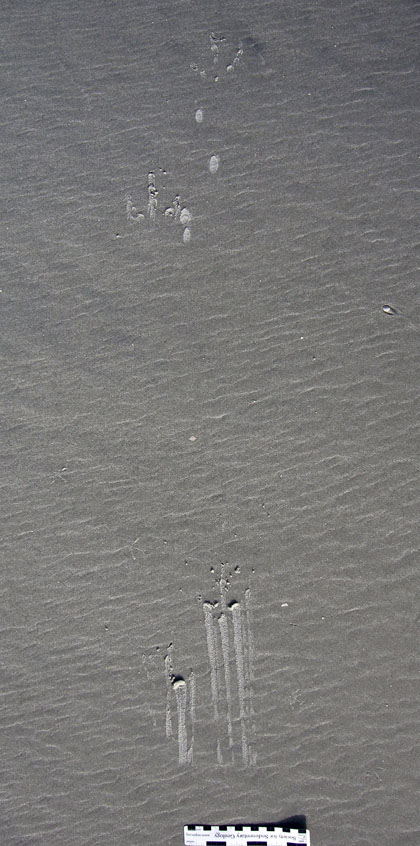

Tracks from a great egret (Ardea alba) on a hard-packed beach sand that say, “I just flew in, and boy are my arms tired.” Notice the offset right-left tracks, long scratch marks left by claws on the rear toes, and cohesive bits of sand pushed forward by the egret’s feet when they contacted the sand. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

Tracks from a great egret (Ardea alba) on a hard-packed beach sand that say, “I just flew in, and boy are my arms tired.” Notice the offset right-left tracks, long scratch marks left by claws on the rear toes, and cohesive bits of sand pushed forward by the egret’s feet when they contacted the sand. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

Now, “flying tracks” may sound contradictory, as a bird in flight leaves no tracks. But for those birds for which flight is an everyday habit, they take off and land, and many of these birds do so on the ground. This fact of avian life is recorded faithfully in the sands and muds of the Georgia barrier islands, and I have often delighted in encountering such tracks made by birds from sparrows to grackles to seagulls to pelicans to great blue herons. When covering this topic in my book (Life Traces of the Georgia Coast, just in case you needed reminding), I had to restrain myself from writing too much about it. Fortunately for readers, though, I described flight traces in enough detail there that I’m confident most people will be able to spot and recognize them. The following pictorial guide, most of which I showed during a recent talk to the Atlanta Audubon Society, should also help.

Flight tracks of a small songbird (probably a species of sparrow) on coastal-dune sands, showing that it didn’t stick around very long: landing, a hop, then take-off. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Little St. Simons Island, Georgia.)

Flight tracks of a small songbird (probably a species of sparrow) on coastal-dune sands, showing that it didn’t stick around very long: landing, a hop, then take-off. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Little St. Simons Island, Georgia.)

How to tell whether a bird was landing or taking off? Your first clue should be a blank area in mud or sand, which will be devoid of tracks just behind a bird trackway, or the opposite, a trackless place just beyond the last footprints. In both instances, tracks are normally paired (side-by-side). For example, here’s an entire sequence made by a common ground dove (Columbina passerina), from landing to walking to take-off.

Entire landing, walking, and take-off sequence for a common ground dove (Columbina passerina) in back-dune area. Notice how it avoided the ghost-crab burrow by walking around it just before deciding to exit the scene. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

Entire landing, walking, and take-off sequence for a common ground dove (Columbina passerina) in back-dune area. Notice how it avoided the ghost-crab burrow by walking around it just before deciding to exit the scene. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

Close-up of landing tracks, in which this ground dove came in from the right, then shuffled its feet to shift direction to its right. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Close-up of landing tracks, in which this ground dove came in from the right, then shuffled its feet to shift direction to its right. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Close-up of take-off tracks, where this ground dove was walking normally, then put its feet together and did one of its typically instant take-offs. (Pro-ichnologist tip: the scratch marks to the right are ghost crab tracks, not wing impressions.) (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Close-up of take-off tracks, where this ground dove was walking normally, then put its feet together and did one of its typically instant take-offs. (Pro-ichnologist tip: the scratch marks to the right are ghost crab tracks, not wing impressions.) (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Look closer at potential flight tracks and you will see other details that tell you whether a bird was coming down to earth or bidding the ground goodbye. Landing tracks often have long impressions behind them, “skid marks” that show how the bird decelerated and controlled its fall through a combination of body positioning and calculated flapping.

For larger birds with a backwards-pointing toe (hallux) – such as herons or egrets – these tracks usually leave a lengthy scratch mark from the claw on that foot. While landing, one foot plants in front of the other – either as an offset right-left or left-right pair – and the first track normally has the longer scratch mark. Either footprint also may have some mounding of mud or sand in front of it, as the forward momentum of the bird exerted pressure against whatever medium it encountered.

Another look at those great egret landing tracks shown previously, but now probably understood a little better through the power of words combined with images. ¡Viva Comunicación de la Ciencia! (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Another look at those great egret landing tracks shown previously, but now probably understood a little better through the power of words combined with images. ¡Viva Comunicación de la Ciencia! (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Close-up of that great egret’s right track, with features showing how its foot slid across the beach surface as it slowed its descent, then stopped. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Close-up of that great egret’s right track, with features showing how its foot slid across the beach surface as it slowed its descent, then stopped. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

In the following video of a sparrow both landing and taking off, watch how it points its rear claws toward the surface as it approaches, then make first contact, followed by the forward-pointing toes. Also notice how one foot barely precedes the other, which in its tracks would should up as a very slight offset between the two. (Warning: This video is exquisitely beautiful, and is best watched with mouth agape in wonder.)

Depending on how fast a bird came down, and taking into account lots of other factors (for example, wind direction and speed), this landing pattern could be followed by a hop, or it could just segue into a normal diagonal walking pattern. Also keep in mind that birds with small or absent halluces (plural of hallux) and full webbing between their toes – such as gulls – may just show their forward three digits skidded, leaving no claw marks in the rear part of the tracks.

Landing tracks of a laughing gull (Leucophaeus atricilla), in which it first skidded, but must have had enough forward momentum to keep it going forward with a big hop. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

Landing tracks of a laughing gull (Leucophaeus atricilla), in which it first skidded, but must have had enough forward momentum to keep it going forward with a big hop. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

Close-up of a different set of landing tracks from a laughing gull with nicely defined skid marks on both feet. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

Take-off patterns involve opposite movements, in which the feet come together, but the digits dig in and push off, leaving scratch marks from the claws and well-defined mounds of sand or mud behind the digits, instead of in front of them. They can also be quite ungainly: I’ve seen pelican and vulture trackways in which they either run or skip for five-six steps before they were aloft, with increasing distances between each successive set of tracks. But sometimes a large bird like a pelican can impress me with its tracks, showing where it successfully accomplished a sudden take-off from a standing start.

Take-off tracks of a brown pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) in which it must have flown from a standing start. Also note the water-drop impressions in front of the tracks, indicating that the pelican had just been in the water and still had wet feathers when it took off. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

So given these search images, lots of birds, and blank canvases of coastal sand or mud, you should now be able to find and diagnose your own “flying tracks.” But you also don’t need to restrict your searches to beaches: these traces can be found wherever flying birds live and visit the ground.

Using such clues, could we ever apply them to recognize flying tracks from the fossil record? Why, yes indeed. And for those of you who read this fair, here’s your Easter egg. The contents of this post relate to a major scientific discovery that will be announced in a few days: you heard it here first. So look for that news to come in for a landing soon.