A little more than a week ago, I co-led a class field trip to Cumberland Island, Georgia and the nearby Okefenokee Swamp for a course titled Ecosystems of the Southeastern U.S. Although I had been to both places more than a few times, none of the students – and a few of my colleagues – had never visited either, potentially casting these already special places in a more exciting light for them.

Nonetheless, as is typical with any field trip to a Georgia barrier island, I also noticed new phenomena while on Cumberland, once again demonstrating how field trips with students ideally also cause the instructors to be filled with wide-eyed wonder. Even better, a few seemingly lowly small bivalves – coquina clams (Donax variabilis) – provided the intellectual highlight for me while we were on Cumberland Island. This is saying something for an island bearing charismatic livestock as a touristic draw.

Resting traces (or are they escape traces?) of coquina clams (Donax variabilis) in the upper intertidal zone of a beach on Cumberland Island, Georgia. These clams are buried just underneath each bump of sand, but some others are much deeper and safer. How do I know that? You’ll find out. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Resting traces (or are they escape traces?) of coquina clams (Donax variabilis) in the upper intertidal zone of a beach on Cumberland Island, Georgia. These clams are buried just underneath each bump of sand, but some others are much deeper and safer. How do I know that? You’ll find out. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

We first noticed the clams as a death assemblage just above the uppermost part of the surf zone on the beach. Their shells, some evident as single valves and others as pairs still hinged together, had been deposited by waves following a high tide, then moved slightly by the wind. These finely ribbed and polished shells readily showed why the specific name of coquina clams (D. variabilis) is applied to them, as they display a gorgeous variety of colors: yellow, orange, beige, blue, pink, and other schemes that surely would inspire interior decorators seeking paisley themes.

Coquina clams with both valves intact or apart, some partially covered by windblown sand, and variably colored. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Cumberland Island, Georgia.)

Coquina clams with both valves intact or apart, some partially covered by windblown sand, and variably colored. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Cumberland Island, Georgia.)

Just a little bit lower on the beach and in the freshly scoured intertidal zone, we then noticed many small bumps of sand. Underneath these bumps were living clams that buried themselves, which helps to avoid drying out between tides or predation by ravenous shorebirds. With regard to the latter, these bivalves still would have been easy targets for shorebirds intent on acquiring some fresh clam snacks: think of a person ducking under a blanket to avoid being eaten by a lion and how well that might work as a tactic. (Please, just think about it and don’t actually test this idea.)

However, instead of simply writing off all coquina clams as inept burrowers who deserve to die at the beaks of their avian overlords – a similar fate experienced by dwarf surf clams (Mulinia lateralis) – we should look well below the surface, and I mean the sand surface. Look again at the photo first shown above. See all of those tiny, paired holes in between the bumps? Those are the traces of siphons from more deeply buried coquina clams, which are much more likely to escape from bivalve-munching birds while also keeping moist until the next high tide.

Here’s the same photo as above, but zoomed in so you can see the details. Did you notice all of the little holes in between shallowly buried clams? If so, bravo. If not, oh well. (Despite the cropping, turning, and otherwise shuffling electrons, this photograph is still by Anthony Martin, and was still taken on Cumberland Island.)

Here’s the same photo as above, but zoomed in so you can see the details. Did you notice all of the little holes in between shallowly buried clams? If so, bravo. If not, oh well. (Despite the cropping, turning, and otherwise shuffling electrons, this photograph is still by Anthony Martin, and was still taken on Cumberland Island.)

Coquina clams are actually accomplished burrowers, a necessary adaptation for nearly any small animal living in the high-energy surf of a Georgia beach. In the event of a wave breaking on a beach and washing away the top layer of sand, thus exposing a coquina clam, it will open its valves only enough to stick out its foot, which it then vibrates rapidly. This movement loosens the wet sand underneath, and the clam’s smooth, streamlined shell does the rest of the job, allowing it to glide into its self-made local pit of quicksand and vanish from the surface.

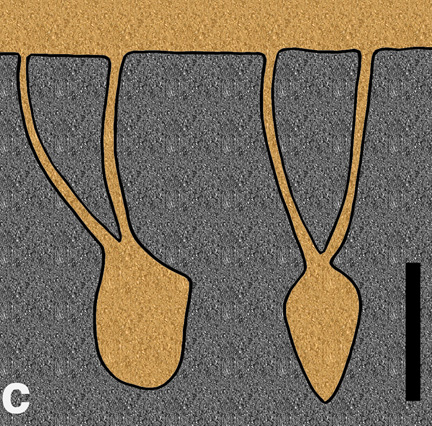

Once under the sand, this clam remains in a vertical position and projects its siphons upwards, making paired holes visible at the sand surface. The resulting burrow is Y-shaped, with the clam body making the lower part of the “Y” and the two siphons leaving thinner traces above. On the Cumberland Island beach the given day we observed their traces, I suspect the more deeply buried clams had the benefit of wetter sand early on as the tide dropped, then the ones hiding under mere caps of sand did the best they could with less wet sand later.

Vertical sections of the Y-shaped burrows made by a coquina clam, dwarf surf clam, or similar small, burrowing bivalves on the Georgia coast, in which the clam body is removed and sediment filled in the empty spaces from above. Both views, taken at right angles from one another, assume the clam is not moving up or down in the sand, which actually isn’t very realistic. (Illustration by Anthony Martin.)

Vertical sections of the Y-shaped burrows made by a coquina clam, dwarf surf clam, or similar small, burrowing bivalves on the Georgia coast, in which the clam body is removed and sediment filled in the empty spaces from above. Both views, taken at right angles from one another, assume the clam is not moving up or down in the sand, which actually isn’t very realistic. (Illustration by Anthony Martin.)

How do we apply this knowledge to the fossil record? Paleontologists have found similar small, Y-shaped burrows in fine-grained sedimentary rocks, trace fossils named Polykladichnus. Some of these burrows are interpreted as the works of suspension-feeding bivalves, although polychaete worms or small arthropods are possible tracemakers, too. Where the lower parts of bivalves rested in sediment and left impressions of their lower halves, which were later filled by overlying sediments, are trace fossils called Lockeia. As a result, paleontologists can reliably identify a former presence of bivalves in rocks that might not have any of their shells. (By the way, please remember that trace fossil names are not the names of the bivalves that made the traces, but of the trace fossil itself. Yeah, I know, that’s confusing. But if you need more of an explanation, I have one for you here.)

So what else is significant about coquina clams? Well, for one, their shells were abundant enough to have formed the framework for a loosely cemented limestone common in Florida, coquina limestone. This is a rock encountered by nearly anyone who has enjoyed (or suffered through) an introductory geology lab exercise on sedimentary rock identification. Students of mine have often compared these rock samples to popcorn balls or similar sugar-cemented treats, although I’ve noticed that no one has been tempted to eat them, no matter how long I kept them in lab that day.

Coquina limestone from Florida. Notice that some of the pieces are from other species of bivalves with rougher, corrugated shells, so these rocks are not made entirely of coquina clams. (Photograph by Mark Wilson of Wooster College, and taken from Wikipedia Commons here.)

Coquina limestone from Florida. Notice that some of the pieces are from other species of bivalves with rougher, corrugated shells, so these rocks are not made entirely of coquina clams. (Photograph by Mark Wilson of Wooster College, and taken from Wikipedia Commons here.)

But I saved the best tidbits of information for last, and something I’ll bet most people don’t know about these clams that makes them, like, totally cool. These little bivalves respond to sound and migrate seasonally. Yes, that’s right: these clams have their own form of “listening” and they can move en masse once the seasons change on the Georgia coast. Here’s how they do both:

Stop, Look, Listen – Of course, clams lack ears (although rumors still persist that they have legs). Thus they do not hear in the sense we do, but instead respond to low-frequency vibrations caused by waves striking the shore. Once these vibrations are detected, they react by: popping out of the sand; jumping up into the water; body surfing on the wave; and quickly reburying themselves in the sand once dumped by that same wave. Like some aficionados of heavy metal or punk rock, louder is better, as higher-decibel waves cause more clams to jump up out of the sand and into the water, an aquatic version of a molluscan mosh pit.

Shelled Migration – Coquina clams, like caribou, wildebeest, and arctic terns, migrate. Unlike the vast distances covered by those animals, though, coquina clams simply move up and down the slope of a beach with the changes of the seasons. Using their wave-surfing and burrowing abilities, they move from the lower intertidal zone – which is where they live during the spring, summer, and fall – to the upper part of the beach, which becomes their winter homes.

So I hope that all of this pondering over a few shells, bumps, and holes on a Cumberland Island beach has helped lend an appreciation for the small wonders on any given Georgia barrier island. Who knows what little discovery the next field trip will bring, or whether some facsimile of what is seen might also be preserved in the fossil record? As the old saying goes, time will tell, whether that time is in the present or the geologic past.

Further Reading

Ellers, O. 1995a. Discrimination among wave-generated sounds by a swash-riding clam. Biological Bulletin, 189: 128-137.

Ellers, O. 1995b. Behavioral control of swash-riding in the clam Donax variabilis. Biological Bulletin, 189: 120-127.

Pemberton, S.G., and Jones, B. 1988. Ichnology of the Pleistocene Ironshore Formation, Grand Cayman Island, British West Indies. Journal of Paleontology, 62: 495-505.

Ruppert, E.E., and Fox, R.S. 1988. Seashore Animals of the Southeast. University of South Carolina Press, Columbia, South Carolina: 429 p.

Turner, H.J., Jr., and Belding, D.L. 1957. The tidal migrations of Donax variabilis Say. Limnology and Oceanography, 2: 120-124.