Following a flurry of dozen posts in December 2013 loosely inspired by The 12 Days of Christmas, this site has been morbidly silent, a veritable vacuum of verbosity. This was probably a good thing, as my life has been occupied by a few other tasks and events, and will be in the near future. So in the proud tradition of Buzzfeed and other Web sites that rely on enumerated click bait for their traffic, here are the top five reasons why I haven’t been blogging lately.

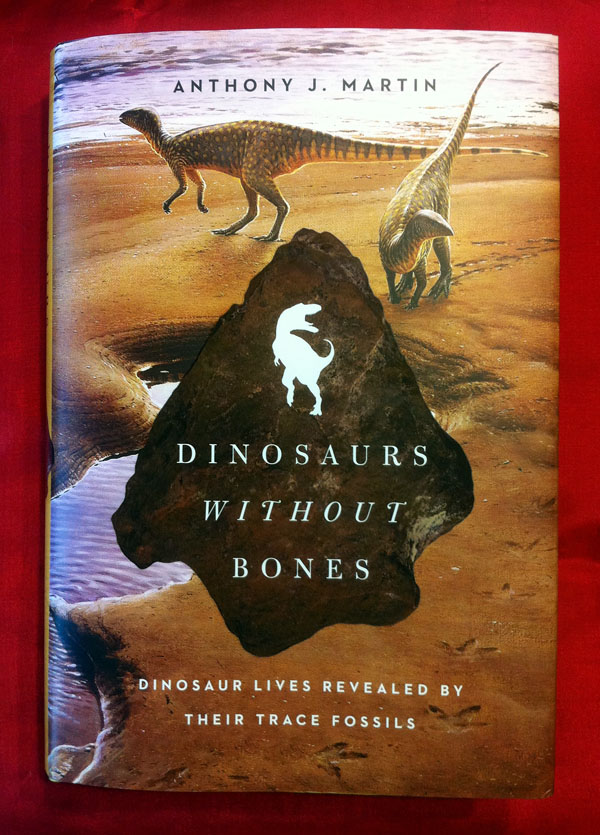

5. I finished writing a book. Titled Dinosaurs Without Bones: Dinosaur Lives Revealed by Their Trace Fossils (Pegasus Books), I’ve been working on it since the summer of 2012, and I’m now holding it in my hands, which is a sure sign that it’s done. Overall, I’m very pleased with how it came out, and even more pleased that it’s out and available for others to enjoy reading. What’s it about? Just re-read the title, but if you’re still not quite sure, I guess you’ll have to get the book and read the whole thing.

Here’s a trace of what I’ve been thinking and writing since 2012. Hope you like it. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken at home.)

Here’s a trace of what I’ve been thinking and writing since 2012. Hope you like it. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken at home.)

4. I taught a field course in the Bahamas. Once every two years, I organize and teach a field course for Environmental Sciences students at my university. This course, which lasts about 10 days, is held during winter break at the Gerace Research Centre on San Salvador Island, Bahamas. Yes, I know, you’re thinking the following: “Can I go?” “Do you need a field assistant?” “That must be nice!” “Poor baby!” [the last of these said sarcastically]. No offense, but I don’t think you would last a day in this course. (Yes, you. And especially you.) It’s a physically demanding course, with land- and water-based field work every day, along with nighttime lectures and discussions, and that happens all before everyone walks 3 km to the nearest bar. Nonetheless, it’s a wildly successful course, in which my initially scared-of-the-outdoors-and-anything-alive-or-dead students are transformed into something approaching field-hardy scientists by the end of their time on the island. I’ll write separately about our latest experiences in an upcoming post, so be looking for that.

Once every two years, this is my classroom. Notice how I even got a student to teach everyone else that day. Not seen in this photo? Fruity drinks with paper umbrellas. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on San Salvador Island, Bahamas.)

Once every two years, this is my classroom. Notice how I even got a student to teach everyone else that day. Not seen in this photo? Fruity drinks with paper umbrellas. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on San Salvador Island, Bahamas.)

3. I gave my first public talk about the new book. First, let me heap some praise on one of the most awesome organizations in the Atlanta area, the Atlanta Science Tavern. With nearly 4,000 members, the Atlanta Science Tavern organizes several science-related talks and events held each month, they’re involved in the upcoming Atlanta Science Festival, and in charge of the Science Track at the Decatur Book Festival, all of which I reckon makes them a force to be, well, reckoned with. Anyway, they invited me to speak about my book as part of their annual Darwin Day Dinner event last month, and I happily complied. It was also great fun being the warm-up act for paleobotantist (and friend) Dr. Melanie DeVore, who spoke later that evening taught us about Darwin’s connection to the “abominable mystery” surrounding the evolution of flowering plants.

2. I co-wrote and submitted a research paper. Sometimes when I’m on San Salvador Island and teaching my students in the field, we make discoveries. So when someone tells you matter-of-factly that teaching and research rarely converge, this pronouncement can be, like, totally falsified when you’re teaching outside of a classroom. Which is to say, outside.

For example, on December 30, while with my students at an coastal limestone outcrop on San Salvador, my student teaching assistant (let’s call her “Meredith”) pointed to some features and said, “Hey Dr. Martin, are these ___________?” To which I replied, “Why yes, I think those are ______________!” (I’d be glad to tell you what they are, but first they have to go through peer review.) So in the past few months, I wrote a draft of a short research paper reporting the find, “Meredith” added her editing suggestions, and we submitted it to an open-access journal for possible publication. But what was really neat about this discovery was that we shared it with the other students in the field, right then, right there, and used it as a teaching lesson on what you should do when making a potential fossil discovery in the field. Take that, false dilemma!

What is life, but a coastal limestone outcrop with a paleosol that is daily immersed by tides and inundated by waves, awaiting discovery of its hidden trace fossils, which are revealed by those same tides and waves? And by the way, watch out for those waves. (Photograph by “Meredith” – which may or may not be her real name – and taken on San Salvador Island, Bahamas.)

What is life, but a coastal limestone outcrop with a paleosol that is daily immersed by tides and inundated by waves, awaiting discovery of its hidden trace fossils, which are revealed by those same tides and waves? And by the way, watch out for those waves. (Photograph by “Meredith” – which may or may not be her real name – and taken on San Salvador Island, Bahamas.)

1. I’ve been teaching (more so). No matter how much it might pain pundits who love to bash those unproductive academics for their non-existent class loads, cushy tenure, exorbitant pay, and – most galling of all – academic freedom, I’ve been teaching 40+ students this semester in two classes, advising a senior honors-thesis student, and helping other students pick out courses for study-abroad programs. Incidentally, I’m also not tenured, my pay is far lower than that of the aforementioned pundits make, and I have no academic freedom (see previous statement about lack of tenure).

For a good summary list of what professors actually do in their jobs, read this. But if you’re one of those people who won’t have your mind changed by evidence-based reasoning, then by all means go back to watching your favorite cable-news show and watch people shout at one another about how climate change is a hoax, whether or not mermaids and Megalodon (or, better yet, a mermaid-eating Megalodon) really do exist, and other fascinating fare. Regardless, I’ve had fun teaching these two classes, although I’m guilty of putting off grading the Bahamas field-course reports. Que sera, sera.

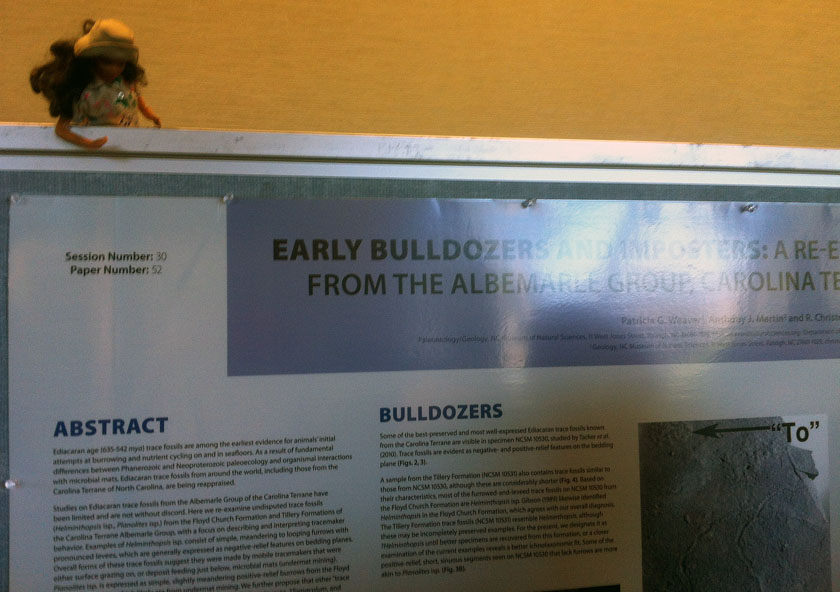

0.5. (Bet you thought you were done, didn’t you?) I attended two conferences in the past few weeks. The first conference is one that meets only once every five years, the North American Paleontological Convention. It’s normally a wonderful conference, and this one – held in Gainesville, Florida and hosted by attended by about 500 paleontologists of all types – was no exception. Indeed, it’s one of the few times we can get micropaleontologists, paleobotantists, invertebrate paleontologists, vertebrate paleontologists, taphonomists, and even ichnologists under the same roof. Other than learning heaps from my paleontological ilk, I presented a talk summarizing Cretaceous trace fossil research I’ve done with colleagues in Victoria, Australia since 2006, and other colleagues of mine at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and I co-authored a poster about Ediacaran fossils in North Carolina. Here’s that poster on Ediacaran fossils from North Carolina, coauthored with Patricia Weaver and Chris Tacker from the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. Notice it’s also undergoing peer-review by our hero, Paleontologist Barbie. Is there nothing she can’t do? (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Gainesville, Florida.)

Here’s that poster on Ediacaran fossils from North Carolina, coauthored with Patricia Weaver and Chris Tacker from the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. Notice it’s also undergoing peer-review by our hero, Paleontologist Barbie. Is there nothing she can’t do? (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Gainesville, Florida.)

The other conference, still fresh on my mind, was Science Online 2014, which was held in Raleigh, North Carolina last week. It was my first time to this conference, and my main reason for going was to promote my book, which was on display there and being given away to lucky attendees in a raffle. But I also had the nice fringe benefits of meeting many very nice (and very smart) folks from the science-communication community who I had only known previously through digital media, while also learning much about online-science communication during sessions on a variety of topics. From what I gathered, a good time was had by most.

What’s coming up in the next future? Plenty! For one, Dinosaurs Without Bones is officially released this Thursday, May 6, 2014. So I’ll probably have something to say about that. Ta-ta for now, and thanks for reading about my latest signs of life, which may or may not preserve in the fossil record.