This past week, I was privileged to have participated in a marvelous three-day field trip to the Triassic and Jurassic sedimentary rocks in and around St. George, Utah. The field trip, organized by paleontologist Andrew Milner and many others in association with the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in Las Vegas, Nevada, provided our enthusiastic group of nearly forty professional and amateur paleontologists with a grand geological tour of southern Utah and northern Arizona, along with the fantastic dinosaur tracksites in that area.

Foremost among these places where dinosaurs left their marks was one of the most incredible tracksites have seen anywhere, which, like Lark Quarry in Queensland, Australia, is enclosed within a building to protect it. This place, called the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm, has one of the few sitting-dinosaur trace fossils known from the fossil record, along with the world’s best collection of dinosaur swimming tracks, rare examples of dinosaur tail-drag marks, hundreds of other dinosaur tracks, and thousands of invertebrate trace fossils. All were enthralling as detailed records of daily life in the Early Jurassic Period, from about 195 million years ago.

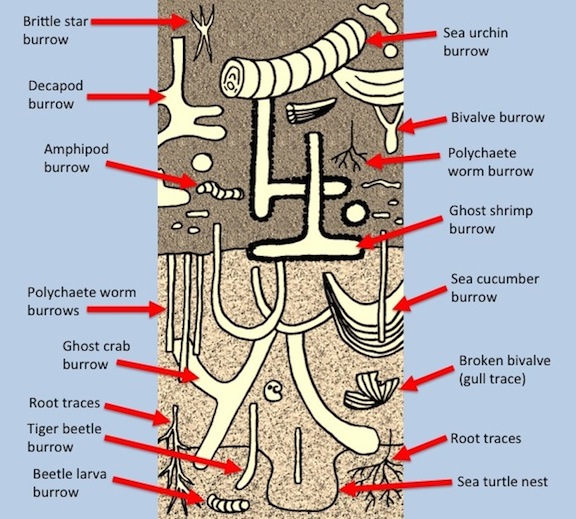

You would think on a field trip like this that Georgia – countering Ray Charles’ memorialized sentiment – would not be on my mind. Yet the modern traces made by living animals of the Georgia barrier islands habitually creep into my thoughts whenever I travel into the geological past. In this instance, the trigger for my thoughts of Georgia traces was through hearing other field-trip participants utter the most recurring of geological clichés connected to invertebrate trace fossils: “worm burrows.”

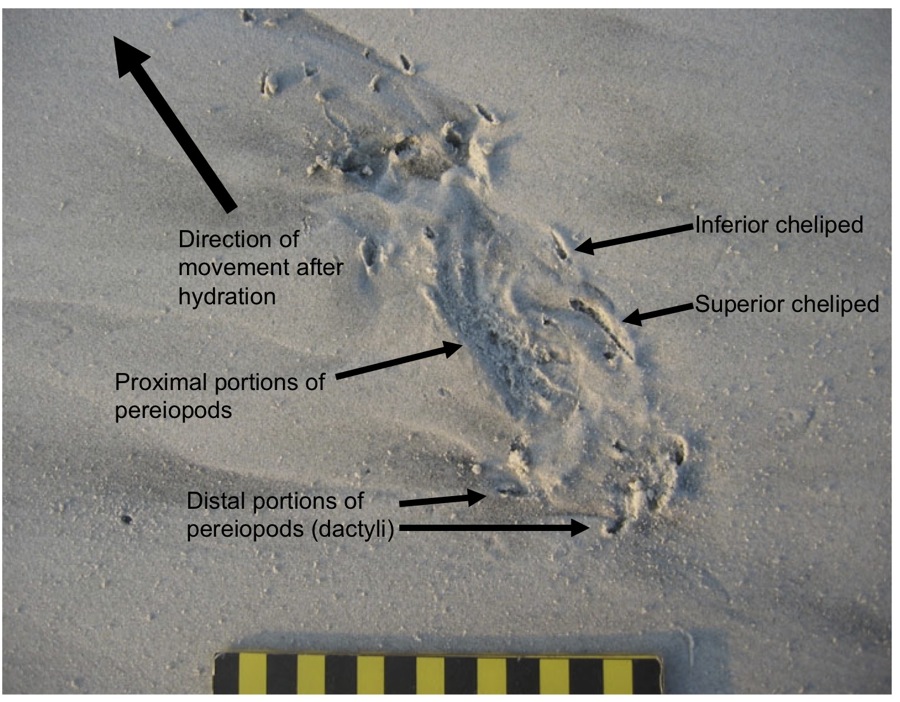

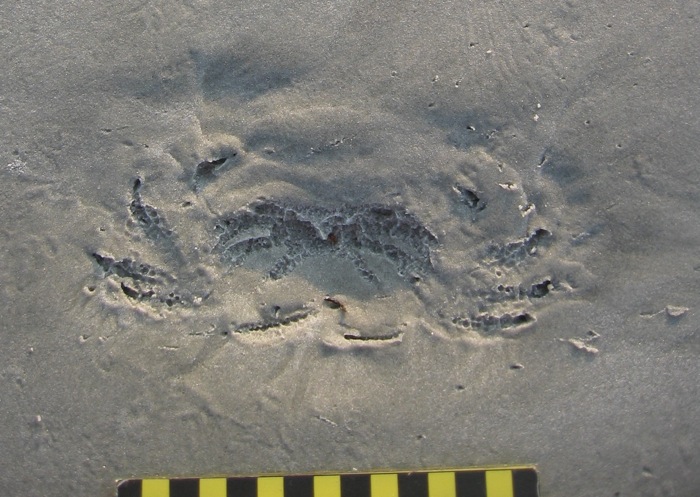

Invertebrate trace fossils (left) directly associated with theropod dinosaur footprints (right) from the Moenave Formation (Lower Jurassic), southern Utah. These trace fossils are probably the burrows of larval insects made in moist muddy sand, rather than burrows made by earthworms in soils. So don’t be calling them “worm burrows,” or else a baby kitten will get mildly scolded. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Invertebrate trace fossils (left) directly associated with theropod dinosaur footprints (right) from the Moenave Formation (Lower Jurassic), southern Utah. These trace fossils are probably the burrows of larval insects made in moist muddy sand, rather than burrows made by earthworms in soils. So don’t be calling them “worm burrows,” or else a baby kitten will get mildly scolded. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Several people spontaneously spoke this ichnological banality as soon as they saw small burrows preserved in the rock, many of which were directly associated with the exquisitely preserved dinosaur tracks. This happened often enough (which is to say, twice) that I just had to call attention to this geological faux pas. “Stop saying ‘worm burrows’!” I said with mock outrage. I quickly followed my joking admonishment with a brief explanation of how most of the burrows were much more likely to be from insects, rather than worms. Traits of the burrows – such as scratchmarks and short, branching, angled tunnels – implied insect tracemakers, such as the larvae of beetles or flies.

Insect traces associated with dinosaur tracks should not be all that surprising to anyone. After all, insects originated in terrestrial environments about 400 million years ago, meaning they were more than halfway through their evolutionary history by the time these Jurassic trace fossils were made. I had seen many similar burrows made by insects on the Georgia barrier islands and elsewhere in Georgia, which gave me enough confidence to propose their more probable identity.

Insect burrows – probably made by “mud-loving” beetles – along the shore of a freshwater pond on Sapelo Island, Georgia. Notice the burrows are relatively younger than (cross-cut) two tail dragmarks made by resident alligators (Alligator mississippiensis). Sandal as scale, which is size 8 1/2 (men’s). (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Insect burrows – probably made by “mud-loving” beetles – along the shore of a freshwater pond on Sapelo Island, Georgia. Notice the burrows are relatively younger than (cross-cut) two tail dragmarks made by resident alligators (Alligator mississippiensis). Sandal as scale, which is size 8 1/2 (men’s). (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Of course, once you draw attention to a word or phrase among friends that is guaranteed to provoke annoyance, you should expect them to bring it up more frequently later as fodder for their amusement. Indeed, this happened for the remainder of the field trip, and I did not disappoint my audience as I responded with histrionic cringing, flinching, and groaning each time we encountered more of these “worm burrows” in Triassic or Jurassic rocks and they were identified as such.

Look, worm burrows! Ha-ha! The beautiful invertebrate trace fossils, former burrows filled with white sand that contrasts from the surrounding hematite-stained sand, are also in the Moenave Formation (Lower Jurassic) of southern Utah. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Look, worm burrows! Ha-ha! The beautiful invertebrate trace fossils, former burrows filled with white sand that contrasts from the surrounding hematite-stained sand, are also in the Moenave Formation (Lower Jurassic) of southern Utah. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

All frivolity aside, the point I was trying to make to my field-trip tormenters was this: whenever we look at sedimentary rocks formed in continental environments, and we happen to notice invertebrate trace fossils in those same rocks, we should think before speaking. In other words, we do better as paleontologists, geologists, or naturalists in general when we reexamine our neat, preconceived labels before applying them loudly and confidently to observed phenomena, and particularly with invertebrate trace fossils.

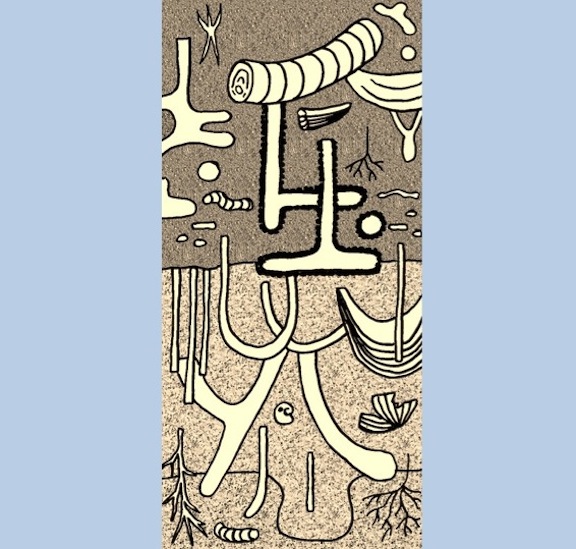

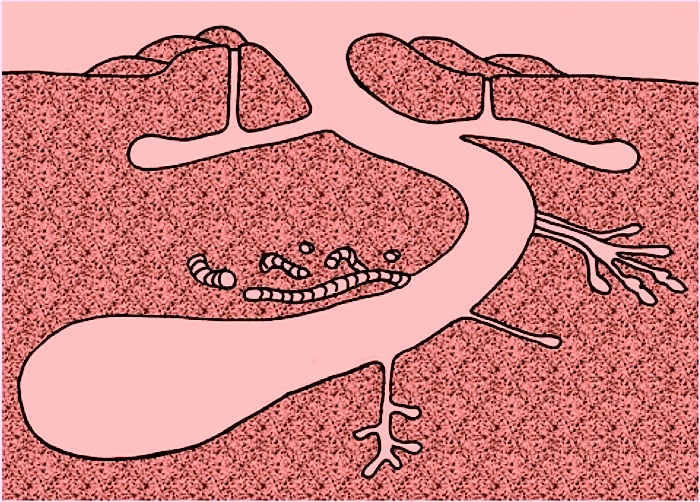

For example, even the word “burrow” can be too glib for interpreting certain invertebrate trace fossils. Many invertebrates do not move underneath a sedimentary surface but along it; traces of such movements are either trackways, which are made with legs and leave impressions of these, or trails, which are made by whole-body movement without legs, such as those formed by worms or snails.

In my experience, trackways and trails are often lumped in with burrows, despite possessing impressions made by legs, furrows, and levees. For example, some of the trace fossils we saw on the field trip were certainly trails, yet I heard these called “burrows” by a few people. Granted, this sort of confusion is actually more understandable than the “worm-burrow” mistake, because trails can segue into shallow horizontal burrows and vice-versa, or some “trails” actually can have tiny leg impressions, meaning they actually are trackways. Thus the distinction between these end members can become blurred quite easily if you don’t pay attention to the details of a given invertebrate trace.

Modern land snail (pulmonate gastropod) making a trail on surface of a coastal dune, Cumberland Island, Georgia; scale in centimeters. (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

Modern land snail (pulmonate gastropod) making a trail on surface of a coastal dune, Cumberland Island, Georgia; scale in centimeters. (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

Fossil trail, possibly made by a snail, on a former sand dune in the Navajo Formation (Lower Jurassic) of southern Utah. Research funding for scale. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Fossil trail, possibly made by a snail, on a former sand dune in the Navajo Formation (Lower Jurassic) of southern Utah. Research funding for scale. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Insect burrow, probably made by a beetle larva, in which it changes from a shallow burrow to a trackway on the surface of a coastal dune, Little St. Simons Island, Georgia. Scale in millimeters. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Insect burrow, probably made by a beetle larva, in which it changes from a shallow burrow to a trackway on the surface of a coastal dune, Little St. Simons Island, Georgia. Scale in millimeters. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

In the sands and muds of the Georgia barrier islands, insect burrows in particular have often caused me to keep quiet about what I think made them, versus what really made them. Many times I have seen a little lump at the end of a horizontal burrow, scooped up the tracemaker hiding underneath, and been surprised by what was there. Most of these tracemakers have turned out to be small adult beetles or beetle larvae of various species, but I can’t ever predict which life stage or species will be there based just on their traces. (At least, not yet.)

Shallow burrow with short branches in a coastal dune, Cumberland Island, Georgia. Gee, I wonder what worm made it?

Shallow burrow with short branches in a coastal dune, Cumberland Island, Georgia. Gee, I wonder what worm made it?

Surprise! It was a tiny adult beetle, found at the end of the burrow. Didn’t see that coming, did you? Well, maybe you did after all of the pedantic foreshadowing. (Both photographs by Anthony Martin.)

Surprise! It was a tiny adult beetle, found at the end of the burrow. Didn’t see that coming, did you? Well, maybe you did after all of the pedantic foreshadowing. (Both photographs by Anthony Martin.)

As a result of these insect-inspired search images, embedded in my consciousness from years of looking at Georgia-coast insect traces, I cannot ever again look at trace fossils made in formerly terrestrial environments and simply say, “worm burrows,” at least with a clear scientific conscience or a straight face. Hence whenever I see similar burrows in sedimentary rocks that were formed in lakes, streams, or soils from the Devonian Period to the recent, my default hypothesis is “insect burrows,” rather than “worm burrows.” Is this always right? No, as some terrestrial trace fossils, such as Edaphichnium and Castrichnus, were almost certainly made by earthworms, and nematode worms may have formed others, like Cochlichnus. (Although Cochlichnus has also been linked with insect tracemakers – but that’s a another story for another day.) Nonetheless, saying “insect burrows” is more likely to be correct than the alternatives, and in science, it’s good practice to learn from your mistakes.

So geologists and paleontologists everywhere, I beseech you not to limit yourselves descriptively when you encounter the millions of lovely and varied invertebrate trace fossils in sedimentary rocks formed in terrestrial environments. The truth will set you free (or at least put you on parole), and these seemingly simple trace fossils will become more intriguing as you realize their full complexity and potential mystery. Call them something other than “worm burrows,” then see what happens.

Invertebrate trace fossils (burrows) in sandstone from the Moeanave Formation (Lower Jurassic) in St. George, Utah. Do they look a little different to you now that you’re ready to give them a different name than mere “worm burrows”? (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Invertebrate trace fossils (burrows) in sandstone from the Moeanave Formation (Lower Jurassic) in St. George, Utah. Do they look a little different to you now that you’re ready to give them a different name than mere “worm burrows”? (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

(Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Andrew Milner, Jim Kirkland, Tyler Birthisel, Martin Lockley, Brent Breithaupt, Neffra Matthews, and many others for their organizing a most excellent three-day field trip to the Triassic-Jurassic rocks of southern Utah and northern Arizona. We all learned heaps from this direct experience, and greatly appreciate the huge amount of time and effort put into preparing for the field trip.)

Further Reading

Milner, A.R.C., Harris, J.D., Lockley, M.G., Kirkland, J.I., and Matthews, N.A. 2009. Bird-like anatomy, posture, and behavior revealed by an Early Jurassic theropod dinosaur resting trace. PLoS One, 4(3): doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004591.

Rindsberg, A.K., and Kopaska-Merkel, D. 2005. Treptichnus and Arenicolites from the Steven C. Minkin Paleozoic footprint site (Langsettian, Alabama, USA). In Buta, R. J., Rindsberg, A. K., and Kopaska-Merkel, D. C., eds., = Pennsylvanian Footprints in the Black Warrior Basin of Alabama, Alabama Paleontological Society Monograph No. 1: 121-141.

Smith, J.J., Hasiotis, S.T., Kraus, M.J., and Woody, D.T. 2008. Relationship of floodplain ichnocoenoses to paleopedology, paleohydrology, and paleoclimate in the Willwood Formation, Wyoming, during the Paleocene–Eocene thermal maximum. Palaios, 23: 683-699.

Verde, M., Ubilla, M., Jiménez, J.J., and Genise, J.F. 2006. A new earthworm trace fossil from paleosols: aestivation chambers from the Late Pleistocene Sopas Formation of Uruguay. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 243: 339-347.