The arrival of Halloween reminds us to celebrate mythical creatures that frighten yet also intrigue us, although recent popular crazes have made this less of an annual event and more year-round. Along those lines, probably the top three of such imaginary beings are zombies, werewolves, and vampires. All of these can be classified as changelings of a sort, with two of them dead, but not really. Here in Georgia, public fascination with zombies has even provided employment opportunities, as many people compete for coveted slots as shuffling extras on the TV series The Walking Dead.

Among these inspirations for Halloween costumes, short stories, novels, musicals, TV shows, and movies, which would be the toughest for an aspiring Van Hesling to track down using ichnological methods? Zombies would be far too easy, considering their slow-moving, foot dragging, bipedal locomotion; their trackways would also commonly intersect as they bump into one another in their search for cranial sustenance. In other words, zombie trackway patterns would closely match those of people texting.

As a result, we have many modern analogs for zombie traces, which would also make their recognition in the fossil record that much easier. Traces made by the zombie-like characters portrayed in 28 Days Later, however, would be far different, showing greater distances between tracks and reflecting more rapid movement. (And all kidding aside, we actually do have trace fossil evidence of zombie ants from about 50 million years ago, an example of reality trumping fiction.)

Similarly, tracking werewolves would be straightforward, in that trackway patterns should show normal human bipedal locomotion followed by abrupt changes to quadrupedal patterns that would range from a trot to full gallop, gaits that are comparatively rare in humans. Anatomical details of tracks would also include a transition from five-toed plantigrade tracks to four-toed digitigrade ones, and metatarsal impressions would be replaced by heel-pad impressions. Additional traces to expect from a werewolf would be the direct effects of successful predation, such as blood spatters, scattering of prey body parts, toothmarks, and so on. (Don’t ask me about werewolf scat, though. I don’t even want to think about some of the things that would show up in that, especially if they started consuming suburbanites.)

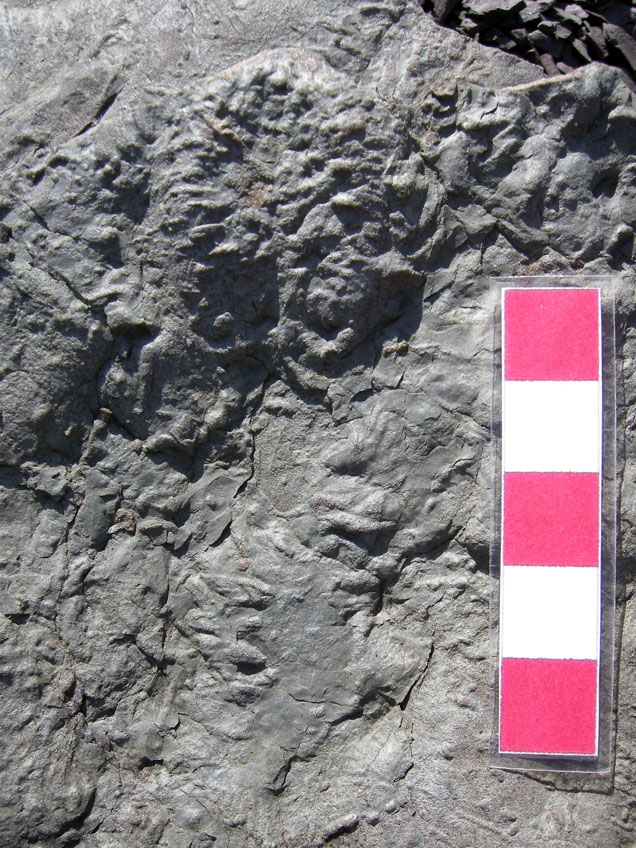

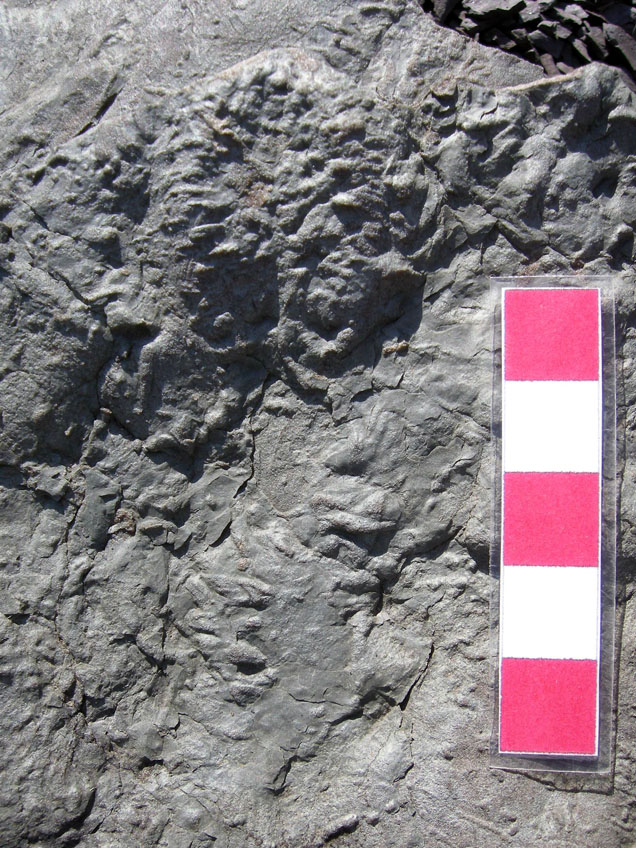

Mixed assemblage of wolf and human tracks, which no doubt proves the existence of werewolves. Or not. Your choice. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming: scale = 10 cm (4 in).)

Mixed assemblage of wolf and human tracks, which no doubt proves the existence of werewolves. Or not. Your choice. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming: scale = 10 cm (4 in).)

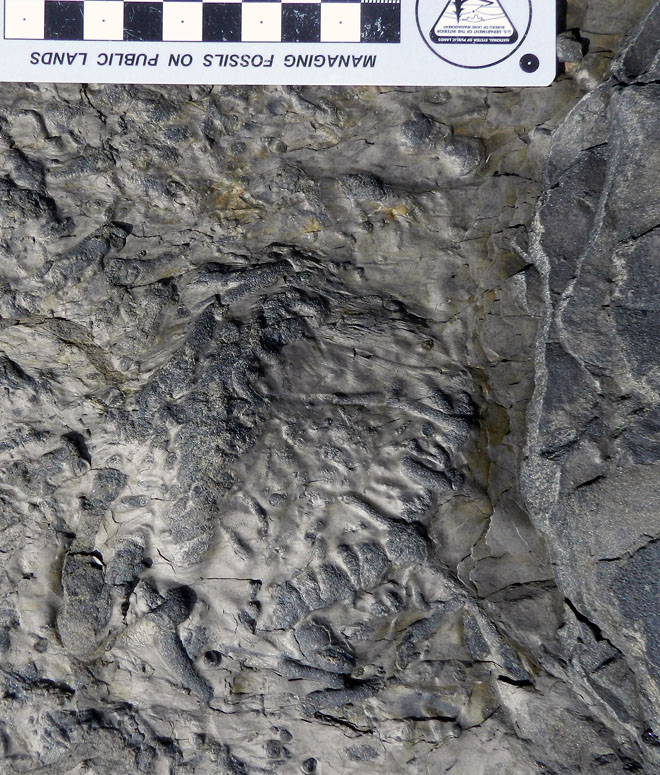

A closer look at those supposed “wolf” tracks. Yes, I know, they’re in the same area of Yellowstone National Park where a successful wolf-release program took place. But my doubt means you have to consider the impossible as equally valid.

A closer look at those supposed “wolf” tracks. Yes, I know, they’re in the same area of Yellowstone National Park where a successful wolf-release program took place. But my doubt means you have to consider the impossible as equally valid.

A gorgeous “wolf” track with evidence of skidding to a halt and turning to the right. Could this have been made immediately after a human transformed into a wolf? My Magic 8-ball says, “Ask again later.”

A gorgeous “wolf” track with evidence of skidding to a halt and turning to the right. Could this have been made immediately after a human transformed into a wolf? My Magic 8-ball says, “Ask again later.”

Scene from some movie I’ll never see, in which one of the characters undergoes a mid-air transformation from a human to a werewolf (Canis lupus hormonensis), abruptly changing his tracks from a more plantigrade bipedal running to digitigrade quadrupedal movement. Sorry, I don’t know if any evidence of teen angst would preserve in such a trackway, nor do I care.

In contrast to zombies and werewolves, vampires would be the most challenging to track, considering their occasional aerial phases of movement, as depicted in Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula (1897) and various popular adaptations. Traces made during a pre-transformation phase – while still in human form – would be indistinguishable from those of a non-undead human, texting or not, and once in the air, no evidence of its movement would be recorded.

A large bat (megachiropteran) in flight, leaving no traces of its passing when traveling in a substrate of air.

So just to leave vampires for a moment, let’s talk about bats, which are real and do leave traces of their activities. Knowing that bats are among the most diverse and abundant of mammals (more than 1,200 species), I made sure to discuss their traces in my upcoming book, Life Traces of the Georgia Coast. Although I personally have not yet seen any of their traces on the Georgia barrier islands, these are predictable and identifiable, so I hold out hope that I or someone else will find them some day.

Probably the most likely traces made by bats that one could encounter on the Georgia barrier islands are their feces, which in other places, through the right geology (think caves) and collective action, can form economic resources (more on that later). About 75% of bat species are insectivores, and because they catch their meals on the fly, their scat will mostly contain winged insect parts. However, the geology of the Georgia barrier islands lacks limestone, and thus precludes the formation of caves or other environments serving as roosting spots for bat colonies. Thus bat feces, such as those dropped by the common brown bat (Myotis lucifugus), will be hard to find unless you look in the right place, such as below a favorite roosting spot. If you are lucky enough to notice these, though, these traces are dark 2-3 mm (0.1 in) wide and 5-15 mm (0.2-0.6 in) long cylinders and filled with parts of flying insects.

Two small samples of bat poop for you. You’re welcome. (Image from Internet Center for Wildlife Damage Management.)

Two small samples of bat poop for you. You’re welcome. (Image from Internet Center for Wildlife Damage Management.)

Most other bats are fruit-eaters; this means these bats, like many birds, are also important seed dispersers through their excreting indigestible seeds covered in fertilizer. Speaking of fertilizers, massive deposits of bat feces (guano) also accumulate in caves and other places where millions of bats have roosted. These nitrogen- and phosphorous-rich deposits have been mined for fertilizers used in agriculture, an example of feeding traces helping to feed people.

Do bats come to the ground and leave tracks? Yes, once in a while they do, where they might forage and walk on all fours. When they do this, they make diagonal walking patterns, contacting with the thumbs on the tips of their wings – which are skin membranes connected to their other, elongated fingers – and their rear feet.

OK, now back to vampires, or rather, vampire bats. There are only three species of parasitic bats, all of which subsist on the blood of other mammals. For feeding, they slice skin with their sharp teeth, which leaves a small (several centimeters long, millimeters thin) incision. They then lap up whatever blood comes out, and the victim often isn’t aware of its blood loss. These wounds also heal, but leave visible scars.

What about other traces left by vampire bats? Surprisingly, scientists have actually asked themselves, “Hey, I wonder how vampire bats get around on the ground?”, and conducted experiments on terrestrial movement of the common vampire-bat (Desmodus rotundus), as well as the short-tailed bat of New Zealand (Mystacina tuberculata).

Just in case you needed another reason why science is cool, these scientists constructed bat-sized treadmills and placed these bats on them. This experiment confirmed that bats, including the common vampire bat, perform an alternating-walking movement in which the rear foot (pes) registers just behind the thumb, which also bears a claw. (This claw comes in handy as a sort of grappling hook at they climb onto their blood sources.)

Walking on Wings from Science News on Vimeo.

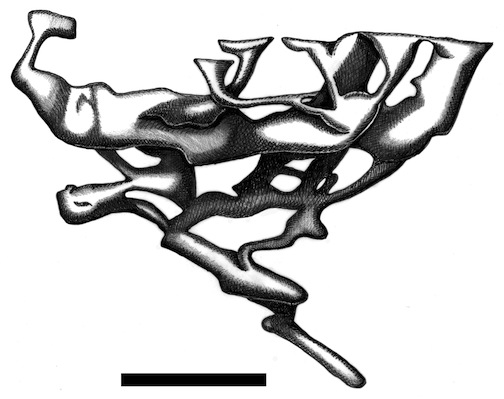

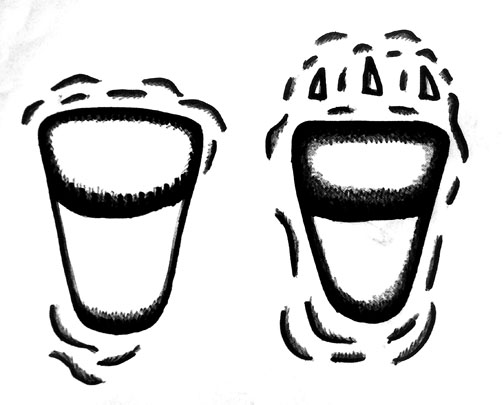

Based on this video, here is what I would hypothesize as the trackway pattern of a walking vampire bat. Note that the rear foot has five digits, nearly equal in length, and that the feet point away from the midline of the trackway.

Based on this video, here is what I would hypothesize as the trackway pattern of a walking vampire bat. Note that the rear foot has five digits, nearly equal in length, and that the feet point away from the midline of the trackway.

But then they found out something most people didn’t expect. When they increased treadmill speeds, the bats bound and almost gallop, in which their rear feet nearly move past their wings. While bounding, these bats land on one of the digits on their wings, then push off with their rear feet, causing a suspension phase, reaching maximum speeds of 1.2 m/s. (Which, incidentally, is about the same speed as most people walking while texting, or slow zombies.) The resulting trackway patterns would be in sets of four – rear feet paired behind thumb impressions – separated from one another by about a body length. Based on my viewing of the videos, the trackways would show both half-bound and full-bound patterns, in which the rear feet are either offset or parallel, respectively.

Vampire Running from Science News on Vimeo.

And here is the hypothesized trackway pattern for a running vampire bat, which is almost like a gallop pattern, but more like a half-bound or full-bound. The feet actually should point a little more inward than during walking, and depending on the substrate, deformation structures might be associated with track exteriors.

And here is the hypothesized trackway pattern for a running vampire bat, which is almost like a gallop pattern, but more like a half-bound or full-bound. The feet actually should point a little more inward than during walking, and depending on the substrate, deformation structures might be associated with track exteriors.

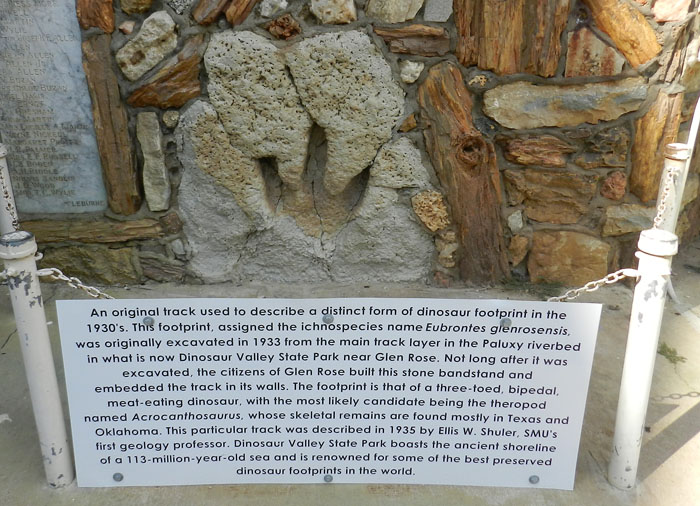

Just to insert a little paleontology into this consideration of bat traces: has anyone found a trackway, feces, or other traces made by bast in the fossil record? No, unless you count old guano deposits as trace fossils (which I would if they exceed 10,000 years old). The body fossil record for bats extends back to the Eocene Epoch, about 50 million years ago, but such fossils are rare, too. Far more impressive than a bat body fossil, though, would be a fossil bat trackway would be the discovery of a lifetime, almost as noteworthy as finding an actual vampire. And if you found a fossil bat trackway where it was running? Time to start playing the lottery.

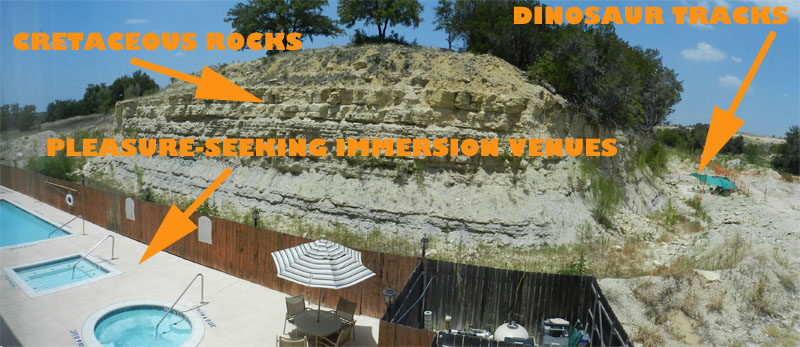

More readily available in ancient strata, though, are pterosaur tracks, whose makers likely walked in a manner similar to bats when on land. Hence bats, although not directly related to these flying reptiles, may provide analogues for how some small pterosaurs moved about when on the ground. Despite their long study and many pterosaur fossils, though, a few people are still arguing about how pterosaurs moved on the ground. So hopefully more studies of bat locomotion will help us to better understand the earthbound behaviors of pterosaurs.

The take-home message of the preceding is that even though zombies, werewolves, and vampires still garner plenty of attention from the public, the truth is that real animals of the past and present – like bats and pterosaurs – are actually more fantastic than we sometimes know. Sure, let’s continue to have fun with our mythical creatures, but in the meantime, also keep an eye out for traces left by the marvelous animals of today and yesteryear.

Further Reading

Elbroch, M. 2003. Mammal Tracks and Sign: A Guide to North American Species. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: 778 p.

Mazin, J.-M., Billon-Bruyat, J.-P., and Padian, K. 2009. First record of a pterosaur landing trackway. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, B, 276: 3881-3886.

Padian, K., and Fallon, B. 2012. Meta-analysis of reported pterosaur trackways: testing the corrspondence between skeletal and footprint records. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 32 [Supplement to 3]: 153.

Riskin, D.K. et al. 2006. Terrestrial locomotion of the New Zealand short-tailed bat Mystacina tuberculata and the common vampire bat Desmodus rotundus. Journal of Experimental Biology, 209: 1725-1736.