(This post is the third in a series discussing academic scientists and public outreach of their science, but with a focus on my recent experiences in using ichnology and paleontology for public outreach. The first of the series, introducing science outreach in general and some of its challenges for academic scientists, is here, and the second, giving an example of how I did public outreach with kids at a local natural history museum, is here.)

During this past week, one of the lessons reinforced from doing public outreach of my science is that, before doing any public event, you first have to ask yourself a very important question: “Who is my audience?” You might think this is a basic question to ask, but it sometimes is not, simply because it takes a lot of courage to change old habits, especially if those habits are constantly rewarded.

Most academic scientists, including paleontologists, are trained to deliver professional talks to their peers, and their peers only. These are formal presentations, using PowerPoint or similar presentation software, which are either 15-20 minutes long (a talk at a professional conference) or a little less than an hour (a talk in a university seminar). In such talks, speakers take full advantage of jargon specific to their field and other verbal accouterments that are intended to set us apart from mere mortals and elevate us among our peers. This sort of presentation style is already a little scary for a lot of us scientists – many of whom are quite introverted – but that’s the standard, and we are rewarded for doing it just like that.

So I understand how doing something different for a presentation, and one not delivered to peers in your scientific field, might seem even scarier. And to depart from this basic model means you could be heading into unknown territory with all sorts of intellectually frightening prospects, of which most paramount is: what if people don’t understand what I’m saying?

Just before giving a public talk at Georgia College and State University this past April, my host, paleobotanist Dr. Melanie DeVore, introduces me, then we perform a ritual greeting with one another as if we are fiddler crabs. Most people in academia would consider this as a non-standard way to start a presentation. (Photograph by Ruth Schowalter, taken at Georgia College and State University in Milledgeville.)

Just before giving a public talk at Georgia College and State University this past April, my host, paleobotanist Dr. Melanie DeVore, introduces me, then we perform a ritual greeting with one another as if we are fiddler crabs. Most people in academia would consider this as a non-standard way to start a presentation. (Photograph by Ruth Schowalter, taken at Georgia College and State University in Milledgeville.)

Like many people who pay attention to science communication, I’ve seen a full spectrum of presentation styles with scientists who do public events. Some of these scientists were fantastically successful in communicating their passions, and I think their success was largely because they really seemed to knew who was there. Here’s also what I’ve seen them do:

- They used a right tone throughout, respectful of the audience, yet confident in conveying their authority on a topic, while throwing in occasional humorous asides.

- They were enthusiastic while remaining coherent.

- They used language appropriate for their audience, applying simpler and less syllabic words in place of multisyllabic jargon.

- Where jargon was used, it was explained in single, easy-to-follow sentences, and then reinforced with visual aids.

- Once in a while they would repeat key points, but not so often that people got bored or (worse) thought the speaker was treating them like they were brain-dead morons.

- Their bodies were an integral part of communicating their science, whether through moving, gesturing, acting out a scientific principle, or even varying facial expressions.

- Their visual aids were perfectly understandable, using photographs of real, phenomena – but taken creatively – and beautiful artwork or graphs that also convey information clearly.

For those academic scientists who were supremely unsuccessful in communicating their science at a public event, they did the opposite of everything I just listed. Regardless, for both end members of this spectrum, I am very grateful for their showing me what works, and what doesn’t.

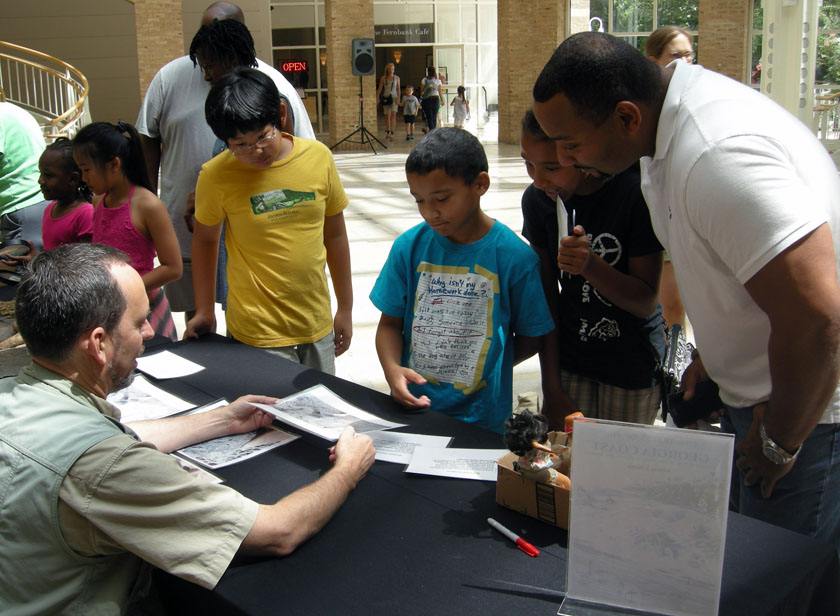

So in my first outreach event, done on Saturday, July 14 at Fernbank Museum of Natural History, my audience mostly consisted of children and their parents. Knowing that very few (if any) of their parents would have been academic scientists, my props, approach, and attitude were prepared with children and non-scientist adults in mind. In such preparations, I knew that visual aids would be important to augment any concepts I wanted to get across. I also knew that I would have to be somewhat basic in any terms I used, but without resorting to “See the dinosaur run. Run, dinosaur, run!” My enthusiasm had to be high, and I would have to be very friendly. Last, I had to be ready for nearly any idea or question to out of their mouths, from very well informed to, well, less so.

Fortunately, these preparations paid off, and I had a wonderful two hours interacting with a wide range of kids, ranging from 4-12 years old, and parents who shared their kids’ excitement about dinosaurs, fossils, and other facets of natural history.

Two days later, on Monday, July 16, I had a very different audience, and one that required a big mental shift from my Fernbank experience, but closer to what academic scientists would consider “normal.” It was the Emory Emeritus College, an organization within my home university. So it was a “home crowd,” and I knew most of them would be receptive to what I had to say. Yet it still represented a small challenge in knowing my audience and figuring out how to deliver it.

The Emory Emeritus College, as one might have figured out from its name, is composed of retired faculty at Emory University. Although I knew some of the faculty from before their retirement, I wanted to learn more about the goals and activities of this organization. I was pleasantly surprised to find out they were part of a nationwide organization, called the Association of Retirement Organizations in Higher Education. What is this? In their own words:

The Association of Retirement Organizations in Higher Education (AROHE) is an international network of retiree organizations at colleges and universities, fosters the development and sharing of ideas to assist member organizations in achieving their purposes and goals.

Along those lines, part of the mission of the Emory group is to foster further learning in retired faculty through regular lunchtime or breakfast-time lectures on a variety of general-interest topics. So I was delighted, several months ago, to have been invited to speak to this group by Dr. Sidney (Sid) Perkowitz. Sid is a retired physics professor who is also one of the few science faculty members at Emory – retired or otherwise – writing trade books intended specifically for public audiences, such as Hollywood Science, Empire of Light, and others. And not just books: he writes articles, essays, stage plays, performance dance pieces, and screenplays. In other words, he’s a pretty cool dude, and a great example of what scientists can become if they want to connect their science to a broader audience.

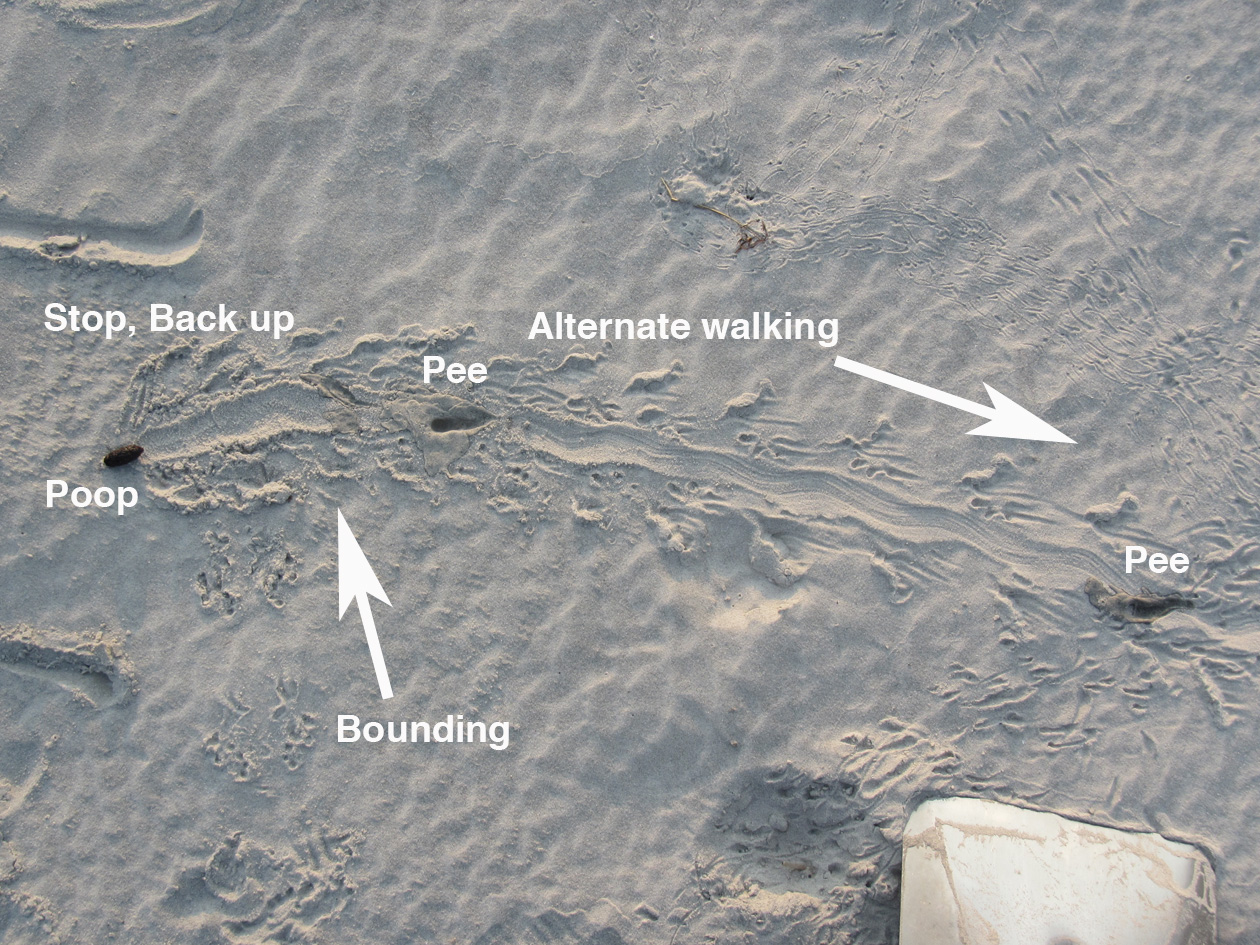

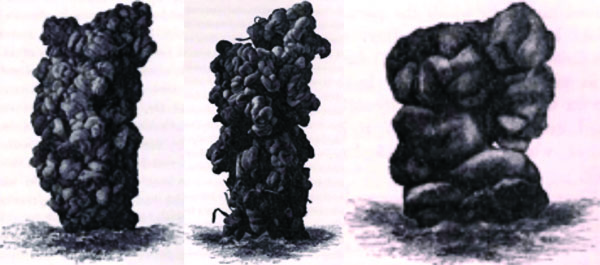

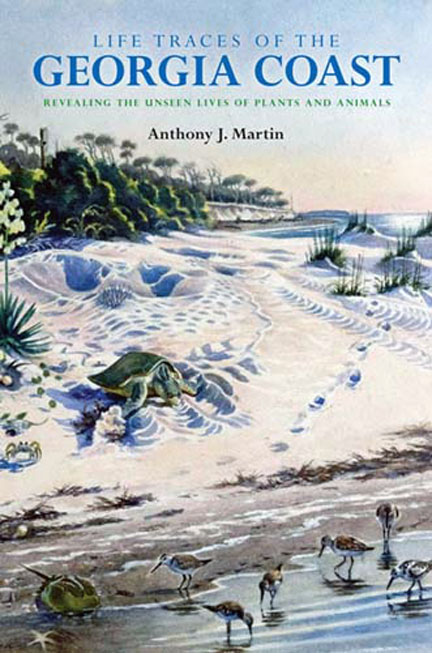

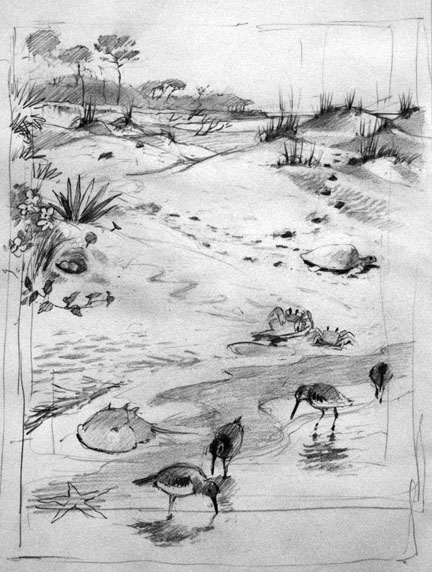

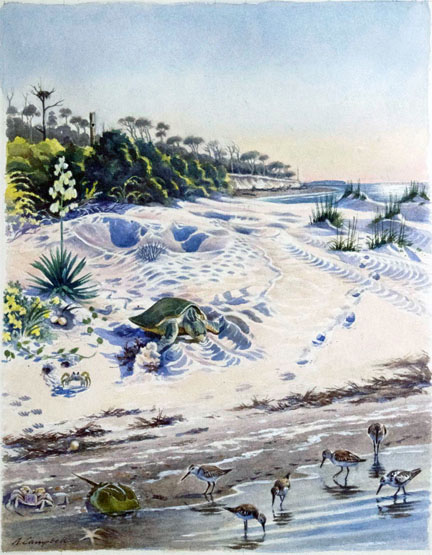

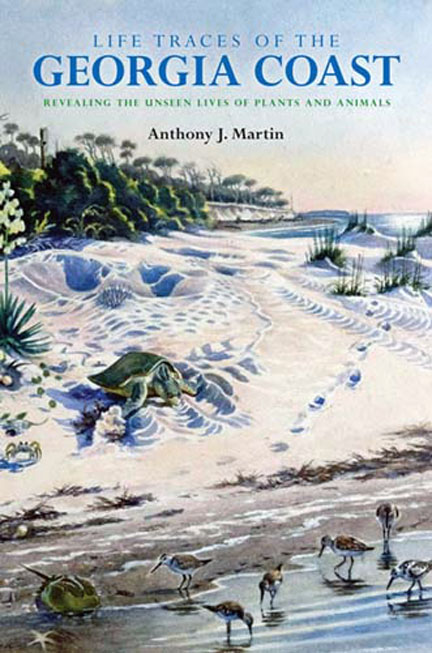

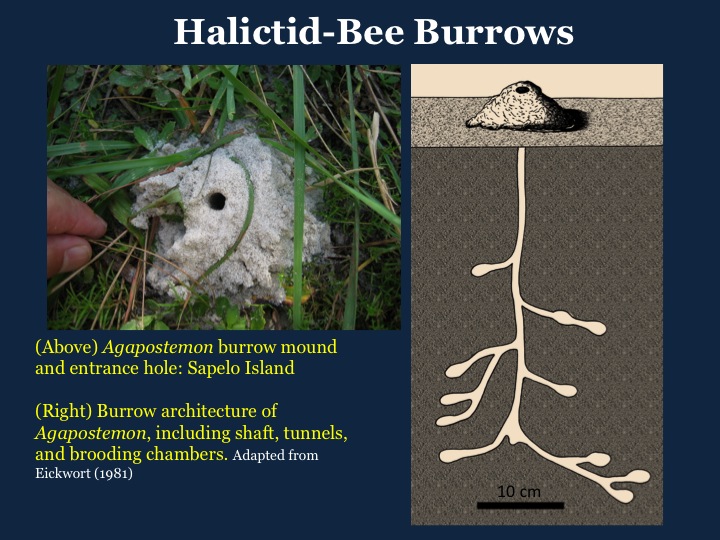

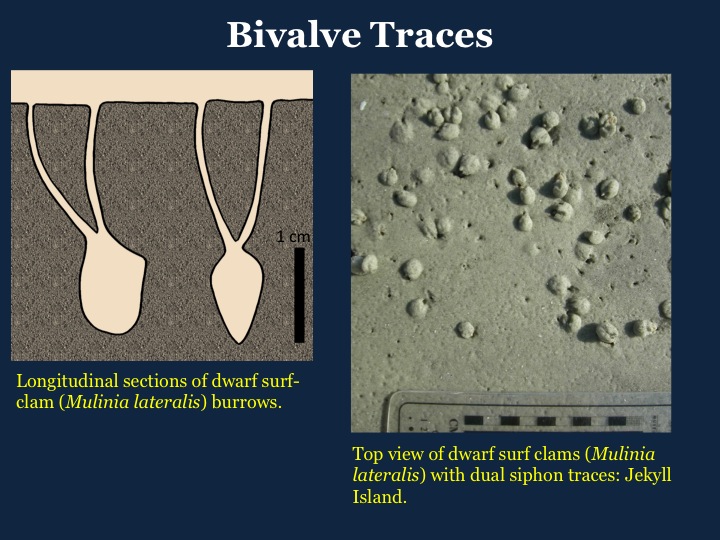

Sid thought that it would be great if I could talk with the emeritus faculty about the topic of my upcoming book (which is, like, you know, the title of this blog). But he also wanted me to mention how I integrate science and art in my work. Fortunately, the standard talk I give to public audiences about the book has plenty of examples of that, provided through my illustrations and photographs that will be in the book. Here are a few samples:

Three examples of slides I’ve used in my standard talk about my book, intended for general audiences, with some combining illustrations of mine and photographs. I know some people would suggest that I use even less text on the slides, but a little bit of information in addition to whatever I’m saying seems to help, too.

Three examples of slides I’ve used in my standard talk about my book, intended for general audiences, with some combining illustrations of mine and photographs. I know some people would suggest that I use even less text on the slides, but a little bit of information in addition to whatever I’m saying seems to help, too.

I suspected this approach – using visual elements to explain the subject of the talk – would work very well with this audience, which was composed of an eclectic group of well-educated people: artists, writers, literary critics, historians, theologians, physicians, chemists, political scientists, and more. Yet I was also keenly aware that just because they retired from teaching at Emory didn’t mean their minds had shut down. This was going to be an engaged, alert bunch.

It worked. About thirty people were there, mostly emeritus faculty, but with a few younger staff helping with the organization of lunch. After a generously laudatory introduction by my hosts, I began with the mystery of the broken bivalve, the opening few pages of the book, but told through images.

They were an attentive audience, with only one person nodding off halfway through my talk, which was much better than what I’ve experienced in a similarly sized class of 18-22year-old students (and following a delicious lunch, so completely understandable). Both planned and unplanned laughs took place throughout the talk, which always helps to relax an audience and me, too.

The time for questions was the part I savored, because I knew they’d be good, conversational ones. Here are three I remember:

- What about the history of ichnology? How long have people been recognizing traces and trace fossils? Answer: It’s as old as humanity, although ichnology has been around as a formal science since the early 19th century.)

- How could someone as young as me be able to do this (ichnology) so well? (This got a good laugh, because I’m 52 years old, which was “young” for this crowd.”) Answer: Lots of practice. (“How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Practice.”) Also, I know I have a long ways to go whenever I’m around peers who are much better at this than me (and older).

- How would this (ichnology) be useful for convincing people that global-climate change is not just some crazy left-wing conspiracy? Answer: The last slide in my talk is a prediction of what will happen on the Georgia coast with increased sea level over the next 100 years or so, and traces will be one more piece of evidence that this is happening.

The most important question, though, was at the very last, and it connected directly with my experience with the children at Fernbank Museum only two days before. What was going to be the future of ichnology if the current generations of children are less likely to go outside and observe nature?

I didn’t really have an answer for this, other than to say that I teach a freshman seminar on tracking at Emory, which gets 18-year-olds out in the classroom, and that some creative combination of digital media that also involves looking at traces outside (such as CyberTracker™) might help, too. It’s not an easy problem to solve, and it’s real. That’s why the first piece of advice I gave kids at Fernbank two days previously was to get outside and enjoy what nature had to teach them.

But this was a key point. Science isn’t just something we learn in college, especially in one required course so we could graduate for non-scientists, or doing it exclusively in a lab with colleagues in academia. It should be life-long learning, or as some science educators say, “from K to gray.” So I see ichnology and the popularizing of it as a science as one solution among many, to make sure that our lives are filled with everyday but awe-inspiring science, from our first toddling steps to our last conscious breaths.