(This is the second in a three-part series honoring the memory of ichnologist-paleontologist-educator-artist Dolf Seilacher (1925-2014). For Part I, please go here.)

Dolf Seilacher and I crossed trails again in the fall of 1997, but through my initiative and in my backyard, here in Georgia. After the Evolutionary Biology Study Group at Emory University hosted a series of prominent biologists on the Emory University campus – such as George C. Williams, Richard Lewontin, and the Grants (Rosemary and Peter) – its director asked me which paleontologist we might bring to campus. Having invited theoreticians and lab-based or field biologists as our main guests, he wanted to give the members of our group more of a “deep time” perspective on evolutionary processes. So I immediately said, “Dolf Seilacher.”

Dolf Seilacher in Melton’s App & Tap, a neighborhood pub near the Emory University campus that served both Coca-Cola (which has economic connections to Emory) and proper adult beverages, the latter necessary for fueling meaningful paleontological conversations. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Atlanta, Georgia 1997.)

Dolf Seilacher in Melton’s App & Tap, a neighborhood pub near the Emory University campus that served both Coca-Cola (which has economic connections to Emory) and proper adult beverages, the latter necessary for fueling meaningful paleontological conversations. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Atlanta, Georgia 1997.)

I recall a few snobbish members of the group doubted that any paleontologist could be a real evolutionary scientist: after all, paleontologists don’t do “experimental work.” (Yes, I’ve actually heard this smug, self-important drivel emit from the mouths of proudly lab-bound neontologists, making Sheldon Cooper look downright open-minded by comparison.) I was also at a university that had jettisoned its Department of Geology only eight years previously, meaning I had little support in my on-campus academic community for hosting an earth scientist. However, Dolf had won the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences Crafoord Prize just five years before, thus he qualified as prestigious enough for most of the doubters. (Needless to say – but it bears saying anyway – none of his prejudiced skeptics had similar honors.)

Fortunately, Dolf did not disappoint, and hosting him at Emory University was among the most intellectually exhilarating three days I’ve experienced in the past 24 years at my institution. I had him mostly to myself on his first day in Atlanta, but we were joined by fellow ichnologist and friend Andrew (Andy) Rindsberg for dinner, with both of us feeling as if we had the world’s best private tutor in ichnology for that brief time. The next day, Dolf did a lunchtime seminar for the Evolutionary Biology Study Group, then later that afternoon delivered a talk in a big room open to the entire university and the general public. For his last full day in Georgia, he insisted we take him out in the field to see some of the Ordovician-Silurian rocks in the northwest corner of the state. (Other than transferring planes in Atlanta’s airport, Dolf had never been to Georgia and wanted to see our trace fossils.)

His second day in Atlanta, he began his engagement with the Evolutionary Biology Study Group, which was composed mostly of biologists, anthropologists, and psychologists; Andy and I were the lone paleontologists there. The lunchtime seminar was held in a cramped room, and most people there were awkwardly holding flimsy paper plates weighed down by slices of cheap pizza. The overall mood was one of curiosity, as Dolf was a complete unknown to most people there. (Remember, this was 1997: “Googling” was still a year away from being anything, let alone a verb.)

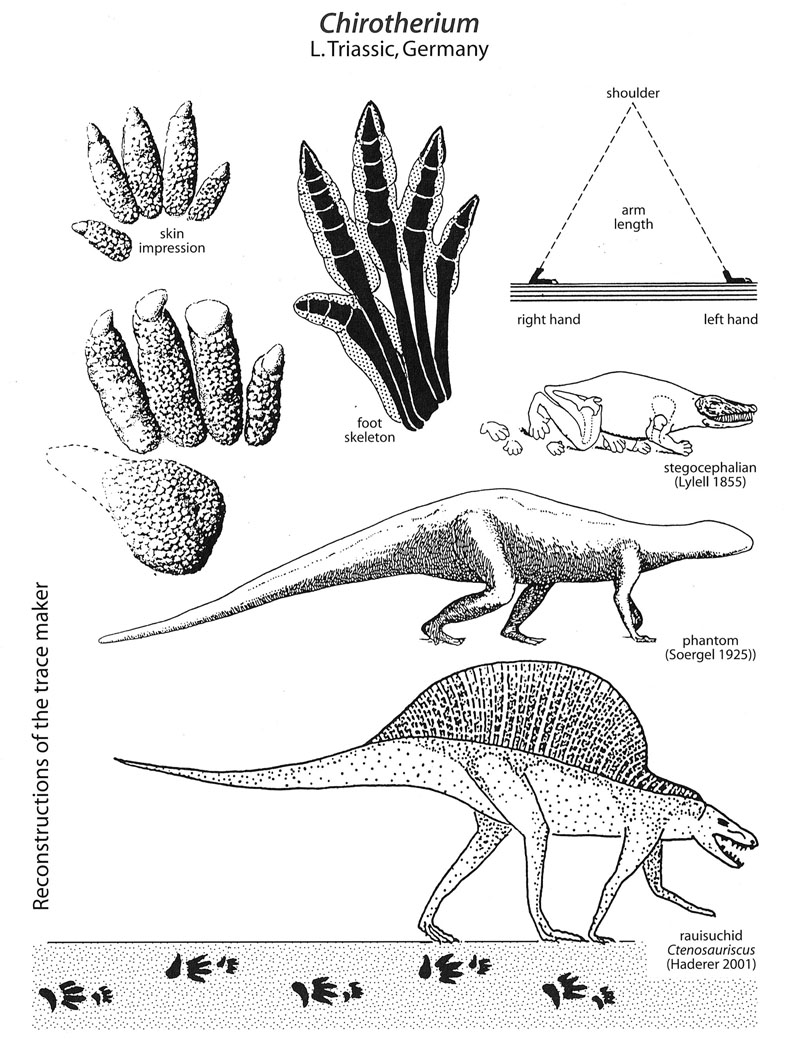

His seminar topic was on fossil tracks, and he started with the classic historical example of how some Early Triassic tracks from Germany (named Chirotherium) had been badly misinterpreted by some of the greatest scientists of their time, such as Alexander von Humboldt, Richard Owen, and Charles Lyell. Later, with more scrutiny and the application of a few key ichnological principles, other scientists revealed what animals made them and how, which Dolf explained in his book Trace Fossil Analysis (2007, p. 6-7).

Dolf Seilacher’s visual explanation for how the anatomy and dimensions of a tracemaker, its behavior, and the original substrate (a firm mud) all contributed to making a fossil trackway from the Early Triassic Period (about 245 million years old). He also included explanations of previous interpretations for these tracks and when they were proposed (middle right), neatly summarizing the progression of the science done on these tracks. (Figure from: Seilacher, A., 2007, Trace Fossil Analysis, Springer, p. 7.)

Dolf Seilacher’s visual explanation for how the anatomy and dimensions of a tracemaker, its behavior, and the original substrate (a firm mud) all contributed to making a fossil trackway from the Early Triassic Period (about 245 million years old). He also included explanations of previous interpretations for these tracks and when they were proposed (middle right), neatly summarizing the progression of the science done on these tracks. (Figure from: Seilacher, A., 2007, Trace Fossil Analysis, Springer, p. 7.)

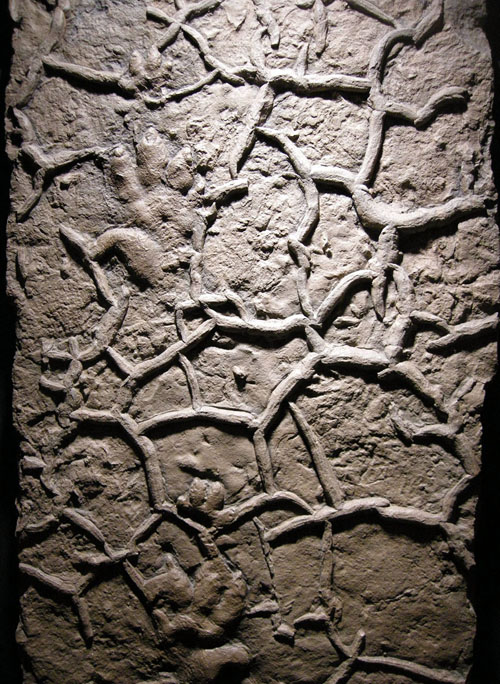

A reproduction of the Early Triassic (about 245 million-year-old) rock slab with mudcracks and Chirotherium tracks, both preserved in convex relief as natural casts. I said “reproduction” because this is a epoxy resin cast made from a latex mold that was also colored to mimic the original rock. Does this sound like a work of art? Well, as a matter of fact, this was one piece in a show Seilacher conceived called Fossil Art. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Krakow, Poland in 2008.)

A reproduction of the Early Triassic (about 245 million-year-old) rock slab with mudcracks and Chirotherium tracks, both preserved in convex relief as natural casts. I said “reproduction” because this is a epoxy resin cast made from a latex mold that was also colored to mimic the original rock. Does this sound like a work of art? Well, as a matter of fact, this was one piece in a show Seilacher conceived called Fossil Art. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Krakow, Poland in 2008.)

Once introduced, Dolf took off, and his audience went with him. In a lively, mesmerizing presentation, Dolf deftly interwove history of science with detective-like applications of ichnology, anatomy, sedimentology, and evolution, all delivered with his trademark enthusiasm, humor, and charisma.

In one memorable instant, he used his hands and arms to play-act the wrongly interpreted gait of the Chirotherium maker, in which this wretched imaginary animal had to cross its limbs as it walked. (Later, paleontologists figured out its so-called “thumb” was actually its outermost digit, thus erasing any need for the animal to cross-step.) He then pantomimed the more correct gait, again bringing across his points far more effectively than if he had used, say, a computer-animated reconstruction of the tracemaker. The audience was enthralled, enchanted, engaged, or whatever words science communicators use to describe what happens when a speaker is rhetorically kicking butt.

How did I know Dolf’s talk was a success? About five minutes into it, one of the most egotistical and pedantic curmudgeons in the Evolutionary Biology Study Group (who may or may not have been an anthropologist) turned to me and said with genuine delight, “This guy is terrific!” Yes, he was.

Later that afternoon, Dolf gave a lecture in a, well, lecture hall, with about a hundred people attending. For me, this was less exciting than his noontime talk because trace fossils and ichnology only figured briefly in its message. Instead, it was more about the “big picture” of evolution as reflected by the fossil record, with emphases on constructional morphology and biological structuralism, and connecting these to the evolution of animal behaviors. Some of these concepts – which I won’t even try to explain here – represented expansions on research by Dolf’s Ph.D. advisor, Otto Schindewolf. Nonetheless, he delivered a thought-provoking lecture, and enthusiastically answered a variety of questions when the time came.

Dinner at a Lebanese restaurant after the lecture was an opportunity to see yet another side of Dolf. For instance, soon after our party had been seated, he and the restaurant owner exchanged pleasantries (and jokes) in Arabic. I had forgotten that Dolf taught at the University of Baghdad early in his career and did much field work in Libya and other parts of the Middle East. The dinner – which included many field stories Dolf had experienced around the world – went well into the night, but did not hinder Dolf’s observation skills at the end of it.

As we exited the restaurant, he pointed to the cement on the doorstep and said, “Look, evidence of a former biomat, helping to preserve this footprint.” We looked down and saw where a shoe-clad human had stepped into the originally wet cement. But wrinkle marks around its edges – as Dolf explained – showed where plastic sheeting had been placed over the cement in a vain attempt to prevent people from stepping on it. It was a moment when we felt like Watson to his Sherlock.

Following his triumphant visit to the Emory campus in Atlanta, Dolf was then ready to experience something that really mattered, like trace fossils. The next day, we took him to northwestern Georgia to look at trace fossils in the Ordovician-Silurian rocks there, a mere 2.5 hour drive from Atlanta.

We had a varied group, composed of a few paleontologists – Andy Rindsberg, Sally Walker, and me – along with the director of the Evolutionary Biology Study Group (Michael Zeiler), a couple of evolutionary biologists and biology graduate students, and a few undergraduate students from one of my geology classes. Our only goal for the day was to see the I-75 Ringgold roadcut, which through its height, breadth, and gently tilted strata afforded an opportunity to stroll along its length, find many trace fossils, and put them into the context of changing environments from more than 440-430 million years ago.

The start of the field trip with Dolf Seilacher to see Ordovician-Silurian rocks near Ringgold, Georgia. This photo was taken about 10 minutes before he took over the field trip, which immediately followed Andy Rindsberg and me getting “Dolfed.” (Photograph taken by Anthony Martin in November 1997.)

The start of the field trip with Dolf Seilacher to see Ordovician-Silurian rocks near Ringgold, Georgia. This photo was taken about 10 minutes before he took over the field trip, which immediately followed Andy Rindsberg and me getting “Dolfed.” (Photograph taken by Anthony Martin in November 1997.)

Andy and I were thrilled to have Dolf at this outcrop with us because we had done a lot of work there, and we wanted to show off what we had found. Andy studied the Ordovician and Silurian trace fossils there in an M.S. thesis done at the University of Georgia, and I completed a bed-by-bed analysis of its Upper Ordovician rocks as part of my Ph.D. dissertation, also at the University of Georgia. Because we worked for the same graduate advisor (Robert “Bob” Frey), Andy and I communicated well with one another, and we mostly agreed on what trace fossils were there and what they meant. Moreover, Frey had published a paper with Dolf in 1980 (well before he died in 1992). Thus Andy and I felt as if we were fulfilling an ichnological legacy by taking Dolf to see trace fossils that Frey had studied here in Georgia.

A first sign that Andy and I were not leading this field trip: within minutes of arriving at the site, the group gathered around Dolf to listen to what he had to say about the Late Ordovician rocks under our feet and around us. Did I mention this was his first time there? (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken near Ringgold, Georgia in November, 1997.)

A first sign that Andy and I were not leading this field trip: within minutes of arriving at the site, the group gathered around Dolf to listen to what he had to say about the Late Ordovician rocks under our feet and around us. Did I mention this was his first time there? (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken near Ringgold, Georgia in November, 1997.)

Probably my favorite photograph of Dolf, showing him in full lecture mode while surrounded by Late Ordovician rocks in northwest Georgia. His synapses also might have been firing double time because of the caffeinated beverage he picked up at a Golden Gallon convenience store just beforehand. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken near Ringgold, Georgia in November, 1997.)

Probably my favorite photograph of Dolf, showing him in full lecture mode while surrounded by Late Ordovician rocks in northwest Georgia. His synapses also might have been firing double time because of the caffeinated beverage he picked up at a Golden Gallon convenience store just beforehand. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken near Ringgold, Georgia in November, 1997.)

When we got to our destination, we parked and walked a short ways to our first stop. Rather than going directly to the road cut, we first looked at big slabs of sandstone in a former quarry site. These sandstones were from the Late Ordovician Sequatchie Formation, and they made for wonderful teaching specimens, containing many fossil burrows, mudcracks, and reddish clay, all indicating formerly intertidal environments. However, Andy and I didn’t know what made the burrows. Little did we know (but we should have), we were about to find out.

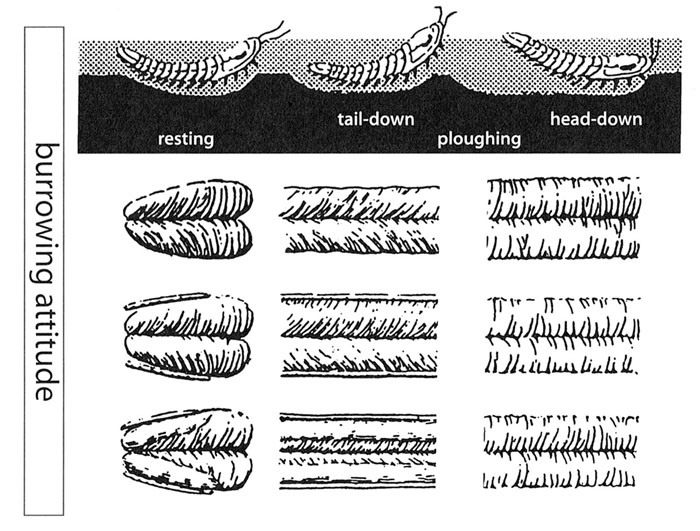

After Andy and I gave a brief introduction to this site and a preview of what to expect at the outcrop, Dolf strolled over to a large slab of sandstone, and nonchalantly placed his hand over a bump on its surface. “This trilobite resting trace shows how they were well adapted to living in intertidal environments at this time…” he began.

Andy and I exchanged startled looks. “Trilobite resting traces?” we both said. In all of our years of field work at this site, we had found very little evidence of a trilobite presence. We also had never recognized a trace fossil showing where a trilobite dug into mud or sand in one place and left an outline of its body, a so-called “resting trace,” sometimes called Rusophycus.

That’s when we realized it. We’d been Dolfed. And on our own field trip.

Fortunately, we didn’t care. Dolf then went on to propose that the more common burrows in these rocks were also made by trilobites, but smaller ones. I’ve written previously about this trilobite-themed revelation and how Andy and I tried later to disprove it, only to find that Dolf was probably right. This served as yet another example of why experience matters in ichnology, and why we ichnologists should always listen to those who have it.

Dolf in action, as he started to put together the story of how trilobites were burrowing on and into tidal flats more than 400 million years ago in a place we now call Georgia. Notice how Dolf was using pencil and paper to assist in his explanations of what was in front of us, no doubt drawing out his conclusions. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken near Ringgold, Georgia in November, 1997.)

Dolf in action, as he started to put together the story of how trilobites were burrowing on and into tidal flats more than 400 million years ago in a place we now call Georgia. Notice how Dolf was using pencil and paper to assist in his explanations of what was in front of us, no doubt drawing out his conclusions. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken near Ringgold, Georgia in November, 1997.)

Dr. Sally Walker, getting a close look at the bedding-plane surface of the sandstone, which is loaded with natural casts of mudcracks. But wait: what’s that blurry, whitish bump in the lower left corner?

Dr. Sally Walker, getting a close look at the bedding-plane surface of the sandstone, which is loaded with natural casts of mudcracks. But wait: what’s that blurry, whitish bump in the lower left corner?

Why, that’s a trilobite resting trace, the first ever found in this formation and locality. Thanks for the Dolfing, Dolf. (Both photographs by Anthony Martin, taken near Ringgold, Georgia in November, 1997.)

Why, that’s a trilobite resting trace, the first ever found in this formation and locality. Thanks for the Dolfing, Dolf. (Both photographs by Anthony Martin, taken near Ringgold, Georgia in November, 1997.)

Don’t quite see the trilobite resting trace fossil, and you think it’s a just a random bump on that rock surface? Here’s an illustration by Dolf that should help to enlighten. Take a look at the left-hand side of this figure with his depictions of trilobite resting traces, then look again at the photograph of the “random bump.” Yes, that’s right: you’re wrong. And you know what? It’s perfectly fine to be wrong in science. Just make sure you learn from your mistakes. (Figure from: Seilacher, A., 2007, Trace Fossil Analysis, Springer, p. 39.)

Don’t quite see the trilobite resting trace fossil, and you think it’s a just a random bump on that rock surface? Here’s an illustration by Dolf that should help to enlighten. Take a look at the left-hand side of this figure with his depictions of trilobite resting traces, then look again at the photograph of the “random bump.” Yes, that’s right: you’re wrong. And you know what? It’s perfectly fine to be wrong in science. Just make sure you learn from your mistakes. (Figure from: Seilacher, A., 2007, Trace Fossil Analysis, Springer, p. 39.)

The rest of the field trip seemed almost anti-climatic after Dolf’s discovery, but it was still quite enjoyable. We left the quarry site and walked along the roadcut itself for the next few hours, stopping to look at whatever caught our attention. Its titled strata meant were were going forward in geologic time, from oldest to youngest (Middle Ordovician –> Early Silurian). This provided a nice lesson for the geological novices in our group in how to interpret changing environments through time. We found more trace fossils, and even a few body fossils, giving everyone plenty of paleontological stimulation to get them through that day and beyond.

Dolf Seilacher, master ichnologist and consumate teacher. We will greatly miss his pointing out the obvious to the oblivious. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken near Ringgold, Georgia in November, 1997.)

Dolf Seilacher, master ichnologist and consumate teacher. We will greatly miss his pointing out the obvious to the oblivious. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken near Ringgold, Georgia in November, 1997.)

When it came time to leave, we walked out with Dolf, feeling exceedingly grateful for his requesting this trip. Later, we joked with him about the success of his “first visit to Georgia.” Alas, we did not know then that it would also his last. Nonetheless, what remains are the provocative thoughts and methods he imparted on so many of us during his brief time here, no doubt inspiring future generations of paleontologists, ichnologists, and all others interested in learning about the wondrous history of the earth.

A group picture following our field trip with Dolf Seilacher to northwest Georgia in November 1997 (and much gratitude to whoever suggested it and took it). For me (far right, big hat), the road behind us seems to symbolize a trail he blazed for us to follow. Thanks for all of the cognitive traces, Dolf: may they continue to reach into the fossil record.

A group picture following our field trip with Dolf Seilacher to northwest Georgia in November 1997 (and much gratitude to whoever suggested it and took it). For me (far right, big hat), the road behind us seems to symbolize a trail he blazed for us to follow. Thanks for all of the cognitive traces, Dolf: may they continue to reach into the fossil record.

Reference

Seilacher, A. 2007. Trace Fossil Analysis. Springer, Berlin: 226 p.