The second day of our Barrier Islands class field trip (Sunday, March 10), which is taking place along the Georgia coast all through this week, involved moving one island north of Cumberland (mentioned in this previous post), to Jekyll Island. I’ve been to Jekyll many times, but none of my students had, so they didn’t quite know what to expect other than what I had told them.

For one, I warned the students that Jekyll was not at all like Cumberland, which is under the authority of the U.S. National Park Service as a National Seashore. Consequently, it has a few residents, but is limited to less than 300 visitors a day. In contrast, many more people visit or live on Jekyll, and people have modified it considerably more. For example, Jekyll has a new convention center, regularly sized and miniature golf courses, a water park, restaurants, bars, and other such items absent during most of its Pleistocene-Holocene history. Another difference is that a ferry was need to get onto Cumberland, whereas we could drive onto Jekyll and stay overnight there in a hotel.

So why go there at all with a class that is supposed to emphasize the geology, ecology, and natural history of the Georgia barrier islands? The main reason for why I chose Jekyll as a destination for these students was so they could see for themselves the balance (or imbalance) between preserving natural areas and human development of barrier islands. Jekyll is one of those islands that is “in between,” where much of its land and coastal areas have been modified by people, but patches of it retain potentially valuable natural-history lessons for my students.

So what you’ll see in the following photos will focus on those more natural parts of Jekyll island, with some of the wonders they hold. However, this series of photos will end with one that will shock and horrify all. Actually, you’ll probably just shake your head and sigh with rueful resignation at the occasional folly of mankind, especially when it comes to managing developed barrier islands.

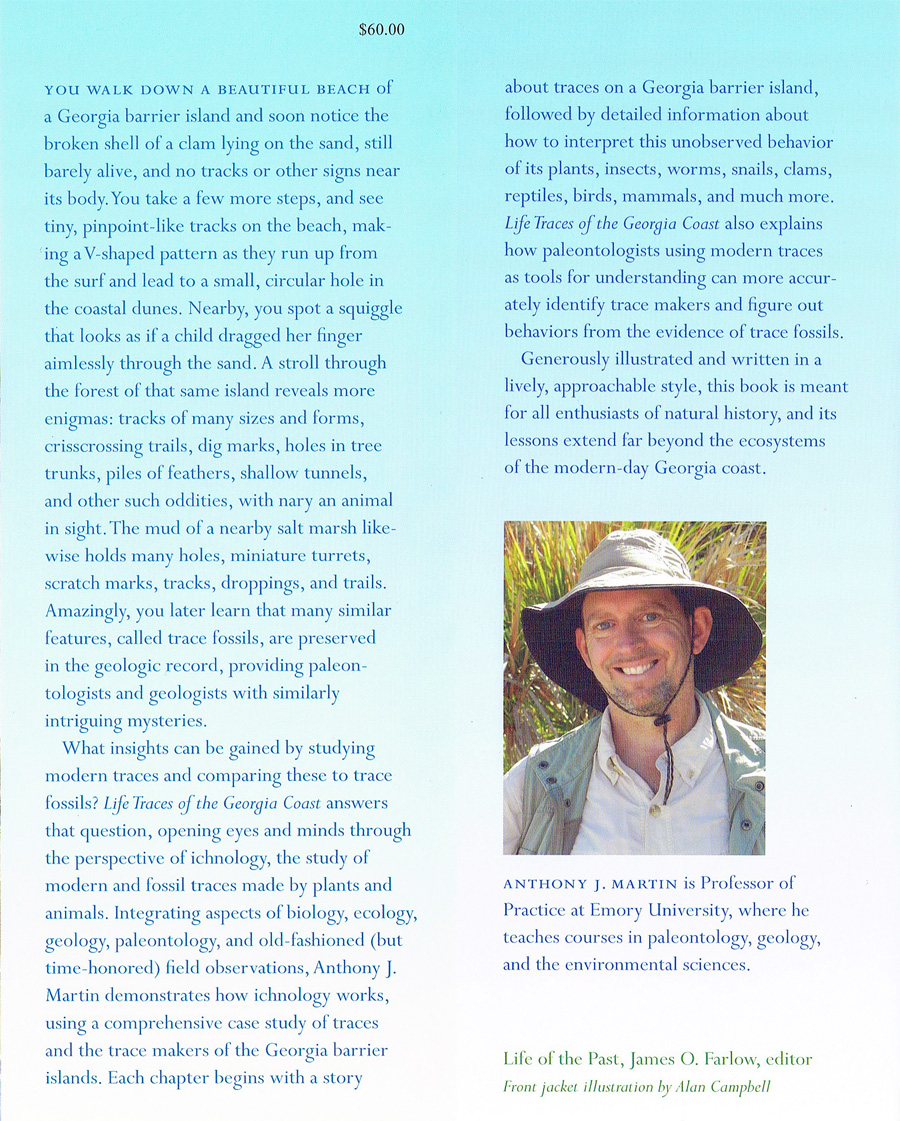

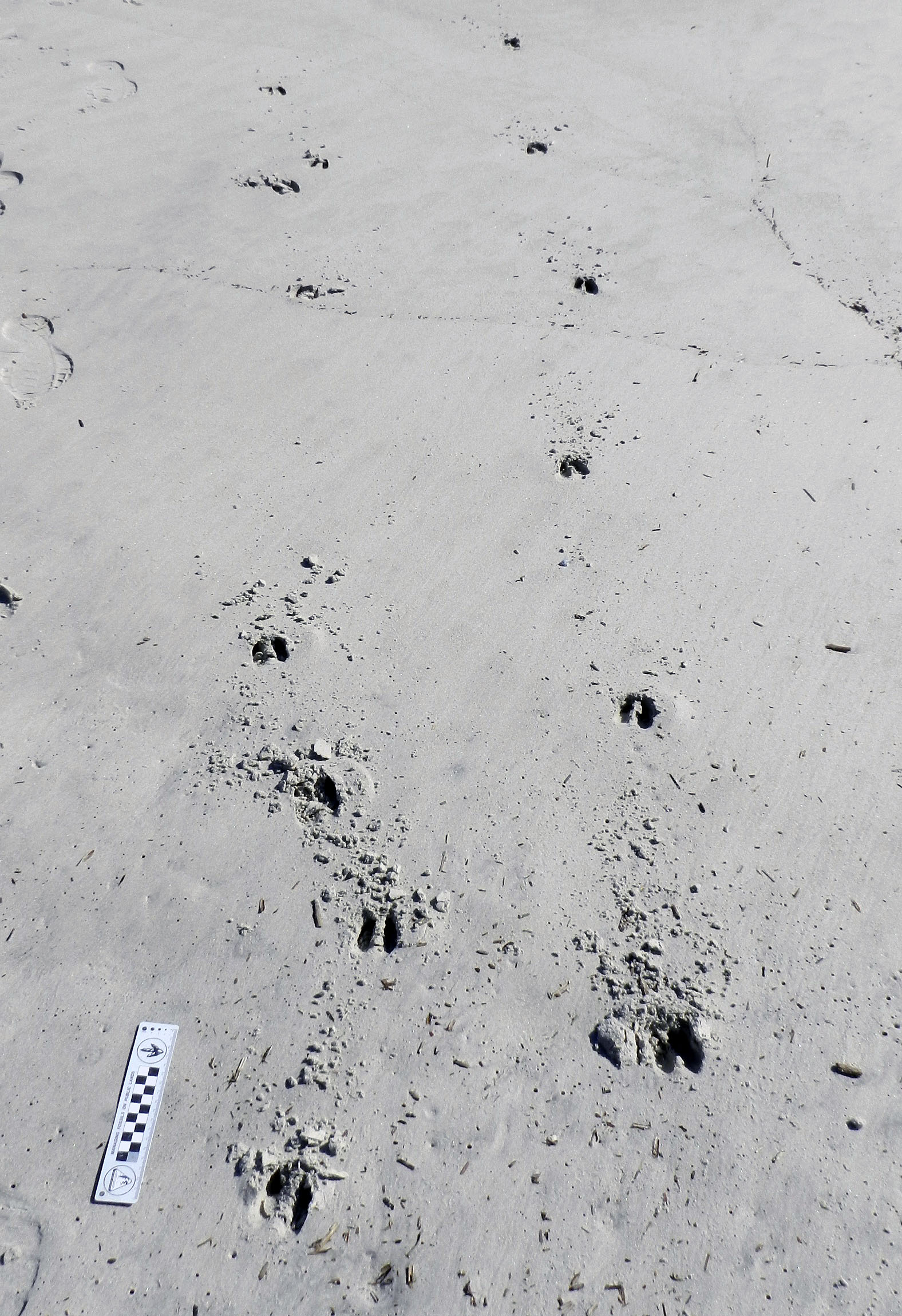

We started our morning like every day should start, with ichnology. Here, tracks of a gray fox, showing direct register (rear foot stepping almost exactly into the front-foot impression) cut between coastal dunes on the south end of Jekyll Island. The presence of gray foxes on Jekyll has caused some curiosity and concern among residents, with the latter emotion evoked because these canids are potential predators of ground-nesting birds, like the Wilson’s plover. Also, people have no idea how many foxes are on the island. If only we had some cost-effective method for detecting their presence, estimating their numbers, and interpreting their behavior. You know, like tracking.

We started our morning like every day should start, with ichnology. Here, tracks of a gray fox, showing direct register (rear foot stepping almost exactly into the front-foot impression) cut between coastal dunes on the south end of Jekyll Island. The presence of gray foxes on Jekyll has caused some curiosity and concern among residents, with the latter emotion evoked because these canids are potential predators of ground-nesting birds, like the Wilson’s plover. Also, people have no idea how many foxes are on the island. If only we had some cost-effective method for detecting their presence, estimating their numbers, and interpreting their behavior. You know, like tracking.

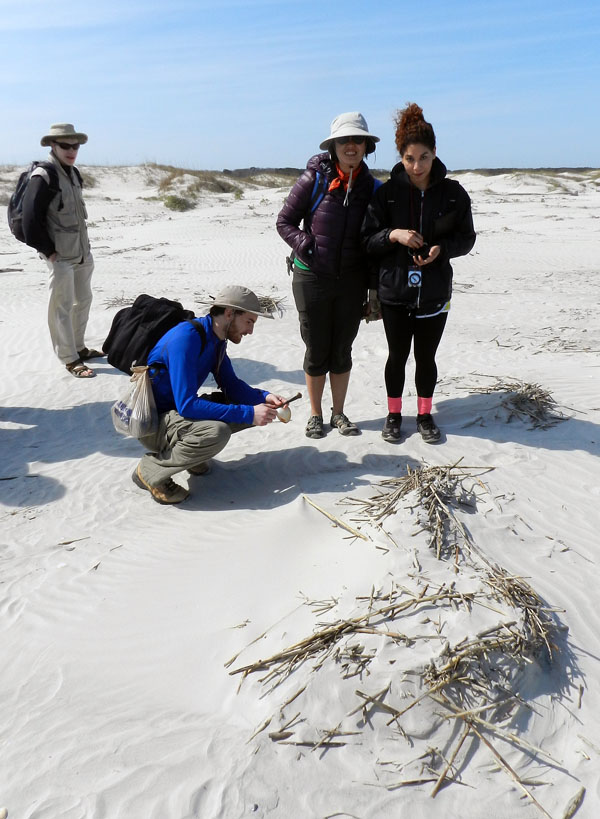

![]() My students show keen interest in the gray fox tracks, especially after I tell them to show keen interest as I take a photo of them. Funny how that works sometimes.

My students show keen interest in the gray fox tracks, especially after I tell them to show keen interest as I take a photo of them. Funny how that works sometimes.

A Wilson’s plover! At least, I think it is.( Birders of the world, please correct me if this is wrong. And I know you will.) We spotted a pair of these birds traveling together on the south end of the island, causing much excitement among the photographers in our group blessed with adequate zoom capabilities on their cameras. Wilson’s plovers are ground-nesting birds, and with both gray foxes and feral cats on the island, their chicks are at risk from these predators. Again, if only we had some cost-effective method for discerning plover-cat-fox interactions. Tracking, maybe?

A Wilson’s plover! At least, I think it is.( Birders of the world, please correct me if this is wrong. And I know you will.) We spotted a pair of these birds traveling together on the south end of the island, causing much excitement among the photographers in our group blessed with adequate zoom capabilities on their cameras. Wilson’s plovers are ground-nesting birds, and with both gray foxes and feral cats on the island, their chicks are at risk from these predators. Again, if only we had some cost-effective method for discerning plover-cat-fox interactions. Tracking, maybe?

Here’s a little secret for shorebird lovers visiting Jekyll Island. Walk around the southwest corner of the island, and you are almost assured of seeing some cool-looking shorebirds along the, well, shore, such as these American oystercatchers, looking coy while synchronizing their head turns. These three were part of a flock of about twenty oystercatchers all traveling together, which I had never seen before on any of the islands. If you go walking on Jekyll, and know where to walk, you’ll see some amazing sights like this.

Here’s a little secret for shorebird lovers visiting Jekyll Island. Walk around the southwest corner of the island, and you are almost assured of seeing some cool-looking shorebirds along the, well, shore, such as these American oystercatchers, looking coy while synchronizing their head turns. These three were part of a flock of about twenty oystercatchers all traveling together, which I had never seen before on any of the islands. If you go walking on Jekyll, and know where to walk, you’ll see some amazing sights like this.

You were probably all wondering what American oystercatcher tracks look like, especially those made by ones that are just standing still. Guess this is your lucky day. Also notice the right foot was draped over the left one, causing an incomplete toe impression on the right-foot one. Wouldn’t it be nice to find a trace fossil just like this?

You were probably all wondering what American oystercatcher tracks look like, especially those made by ones that are just standing still. Guess this is your lucky day. Also notice the right foot was draped over the left one, causing an incomplete toe impression on the right-foot one. Wouldn’t it be nice to find a trace fossil just like this?

Black skimmers! We didn’t get to see them skim, but we still marveled at this flock of gorgeous shorebirds. These were in front of the oystercatchers, with an occasional royal tern slipping into the party, uninvited but seemingly tolerated.

Black skimmers! We didn’t get to see them skim, but we still marveled at this flock of gorgeous shorebirds. These were in front of the oystercatchers, with an occasional royal tern slipping into the party, uninvited but seemingly tolerated.

Yeah, I know, you also wanted to know what black skimmer tracks look like. So here they are. Now you don’t need to use a bird book to identify this species: just look at their tracks instead!

Yeah, I know, you also wanted to know what black skimmer tracks look like. So here they are. Now you don’t need to use a bird book to identify this species: just look at their tracks instead!

You think you’re bored? Try being driftwood, with marine clams out there adapted for drilling into your dead, woody tissue. This beach example prompted a nice little lesson in how this ecological niche for clams has been around since at least the Jurassic Period, which we know thanks to ichnology. You’re welcome (again).

Beach erosion at the southernmost end of Jekyll gave us an opportunity to see the root systems of the main tree species there, such as this salt cedar (actually, it’s a juniper, not a cedar, but that’s why scientists use those fancy Latinized names, such as Juniperus virginiana). My students are also happily learning to become the scale in my photos, although I suspect they will soon tire of this.

Beach erosion at the southernmost end of Jekyll gave us an opportunity to see the root systems of the main tree species there, such as this salt cedar (actually, it’s a juniper, not a cedar, but that’s why scientists use those fancy Latinized names, such as Juniperus virginiana). My students are also happily learning to become the scale in my photos, although I suspect they will soon tire of this.

Look at this beautiful maritime forest! This is what I’m talking about when I say “…patches of it [Jekyll Island] retain potentially valuable lessons in natural history.” This is on the south end of the island, and this view is made possible by walking just a few minutes on a trail into the interior.

Look at this beautiful maritime forest! This is what I’m talking about when I say “…patches of it [Jekyll Island] retain potentially valuable lessons in natural history.” This is on the south end of the island, and this view is made possible by walking just a few minutes on a trail into the interior.

Few modern predators, invertebrate or vertebrate, provoke as much pure unadulterated giddiness in me as mantis shrimp. So imagine how I felt when, through sheer coincidence, a couple walked into the 4-H Tidelands Nature Center on Jekyll, while I was there with my class, and asked if I identify this animal they found on a local beach. The following are direct quotations from me: “Wow – that’s a mantis shrimp!! Squilla empusa!! It’s incredible!!” I had never seen a live one on the Georgia coast, and it was a pleasure to share my enthusiasm for this badass little critter with my students (P.S. It makes great burrows, too.)

Few modern predators, invertebrate or vertebrate, provoke as much pure unadulterated giddiness in me as mantis shrimp. So imagine how I felt when, through sheer coincidence, a couple walked into the 4-H Tidelands Nature Center on Jekyll, while I was there with my class, and asked if I identify this animal they found on a local beach. The following are direct quotations from me: “Wow – that’s a mantis shrimp!! Squilla empusa!! It’s incredible!!” I had never seen a live one on the Georgia coast, and it was a pleasure to share my enthusiasm for this badass little critter with my students (P.S. It makes great burrows, too.)

A stop at the Georgia Sea Turtle Center on Jekyll was important for my students to learn about the role of the Georgia barrier islands as places for sea turtles to nest. But I had been there enough times that I had to find a way to get excited about being there yet again. Which is why I took a photo of their cast of the Late Cretaceous Archelon, the largest known sea turtle. I never get tired thinking about the size of the nests and crawlways this turtle must have made during the Cretaceous Period, perhaps while watched by nareby dinosaurs.

A stop at the Georgia Sea Turtle Center on Jekyll was important for my students to learn about the role of the Georgia barrier islands as places for sea turtles to nest. But I had been there enough times that I had to find a way to get excited about being there yet again. Which is why I took a photo of their cast of the Late Cretaceous Archelon, the largest known sea turtle. I never get tired thinking about the size of the nests and crawlways this turtle must have made during the Cretaceous Period, perhaps while watched by nareby dinosaurs.

At the north end of Jekyll, shoreline erosion has caused the beach and maritime forest to meet, and the forest is losing to the beach. This has caused the forest to become what is often nicknamed a “tree boneyard,” in which trees die and either stay upright or fall in the same spot where they once practiced their photosynthetic ways.

At the north end of Jekyll, shoreline erosion has caused the beach and maritime forest to meet, and the forest is losing to the beach. This has caused the forest to become what is often nicknamed a “tree boneyard,” in which trees die and either stay upright or fall in the same spot where they once practiced their photosynthetic ways.

Quantify it! Whenever we encountered dead trees with root systems exposed, I asked the students to measure the vertical distance from beach surface to the topmost horizontal roots. This gave an estimate of the minimum amount of erosion that took place along the beach.

Quantify it! Whenever we encountered dead trees with root systems exposed, I asked the students to measure the vertical distance from beach surface to the topmost horizontal roots. This gave an estimate of the minimum amount of erosion that took place along the beach.

Perhaps a more personal way to convey the amount of beach erosion that happened here was to see how it related to the students’ heights. It was a great teaching method, well worth the risk of being photobombed.

Perhaps a more personal way to convey the amount of beach erosion that happened here was to see how it related to the students’ heights. It was a great teaching method, well worth the risk of being photobombed.

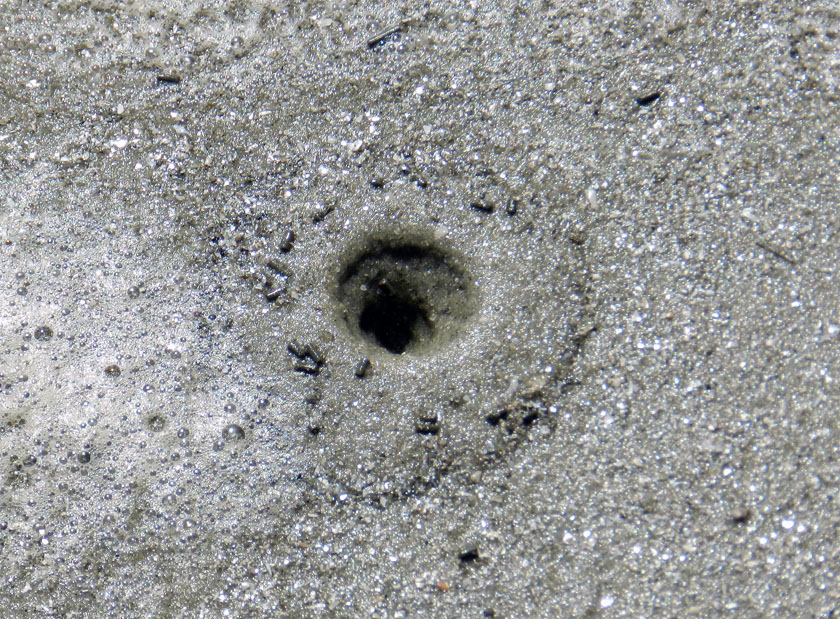

Are you ready? Here it is, in three parts, what was without a doubt the traces of the day. Start from the lower left with that collapsed burrow, follow the tracks from left to right, and look at that raised area on the right.

Are you ready? Here it is, in three parts, what was without a doubt the traces of the day. Start from the lower left with that collapsed burrow, follow the tracks from left to right, and look at that raised area on the right.

A close-up of the raised area shows a chevron-like pattern, implying that this was an animal that had legs, and knew how to use them. Wait, is that a small part of its tail sticking out of the left side?

A close-up of the raised area shows a chevron-like pattern, implying that this was an animal that had legs, and knew how to use them. Wait, is that a small part of its tail sticking out of the left side?

Violá! It was a ghost shrimp! I almost never see these magnificent burrowers alive and outside of their burrows, and just the day before on Cumberland Island, the students had just learned about their prodigious burrowing abilities (the ghost shrimp, that is, not the students). I had also never before seen a ghost shrimp trackway, let alone one connected to a shallow tunnel on a beach. An epic win for ichnology!

Violá! It was a ghost shrimp! I almost never see these magnificent burrowers alive and outside of their burrows, and just the day before on Cumberland Island, the students had just learned about their prodigious burrowing abilities (the ghost shrimp, that is, not the students). I had also never before seen a ghost shrimp trackway, let alone one connected to a shallow tunnel on a beach. An epic win for ichnology!

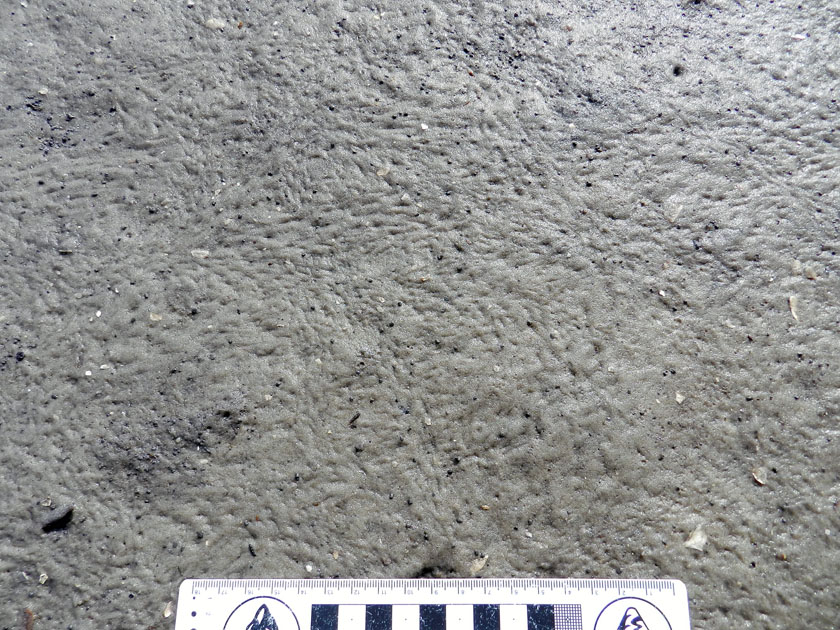

This may look like soft-serve ice cream, but I suspect that it’s not nearly as tasty. It’s the fecal casting of an acorn worm (Balanoglossus sp.), and is composed mostly of quartz sand, but still. These piles were common on the same beach at the north end of Jekyll, but apparently absent from the south-end beach. Why? I’m guessing there was more food (organics) provided by a nearby tidal creek at the north end. But I’d appreciate all of those experts on acorn worms out there to augment or modify that hypothesis.

This may look like soft-serve ice cream, but I suspect that it’s not nearly as tasty. It’s the fecal casting of an acorn worm (Balanoglossus sp.), and is composed mostly of quartz sand, but still. These piles were common on the same beach at the north end of Jekyll, but apparently absent from the south-end beach. Why? I’m guessing there was more food (organics) provided by a nearby tidal creek at the north end. But I’d appreciate all of those experts on acorn worms out there to augment or modify that hypothesis.

This is how dunes normally form on Georgia barrier-island beaches: start with a rackline of dead smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora), then windblown sand begins to accumulate in, on, and around these. Throw in a few windblown seeds of sea oats and a few other dune-loving species of plants, and next thing you know, you got dunes. Dude.

This is how dunes normally form on Georgia barrier-island beaches: start with a rackline of dead smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora), then windblown sand begins to accumulate in, on, and around these. Throw in a few windblown seeds of sea oats and a few other dune-loving species of plants, and next thing you know, you got dunes. Dude.

In contrast, here is how not to form dunes on Georgia barrier-islands beaches. Build a concrete seawall on the middle part of the island, truck in thousands of tons of metamorphic rock from the Piedmont province of Georgia, place the rocks in front of the seawall, and watch the beach shrink. So sad to see all of that dune-building smooth cordgrass going to waste. Anyway, the contrast and comparison you just saw is also what my students experienced by standing in both places the same day.

In contrast, here is how not to form dunes on Georgia barrier-islands beaches. Build a concrete seawall on the middle part of the island, truck in thousands of tons of metamorphic rock from the Piedmont province of Georgia, place the rocks in front of the seawall, and watch the beach shrink. So sad to see all of that dune-building smooth cordgrass going to waste. Anyway, the contrast and comparison you just saw is also what my students experienced by standing in both places the same day.

Jekyll Island gave us many lessons, but we only had a day there. Which islands were next? St. Simons and Little St. Simons, with emphasis on the latter. So look for those photos in a couple of days, in between new exploits and learning opportunities.