As I wrote this post, I was flying from Atlanta, Georgia to Minneapolis, Minnesota to attend the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America (GSA), where I’ll be with about 7-8,000 geoscientists from across and outside of the U.S. Why am I not doing something else, such as field work on the Georgia coast? Well, other than to learn the latest of what’s happening in the world of geology, seeing old friends, and meeting new ones, I’m here to share new scientific knowledge coming out of the Georgia coast with my fellow geologists and paleontologists. The subject of the presentation I will give tomorrow – Tuesday, October 11 – is about the wondrous burrows of a humble-looking, slow-moving, and seemingly lethargic reptile that actually is an ichnological force of nature: the gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus).

A gopher tortoise in captivity, but living a safe and happy life at the 4-H Tidelands Nature Center on Jekyll Island, Georgia. Although it may not look like a big deal, it is a very impressive tracemaker, deserving the rapt attention of geologists and paleontologists. (Photograph taken by Anthony Martin.)

A gopher tortoise in captivity, but living a safe and happy life at the 4-H Tidelands Nature Center on Jekyll Island, Georgia. Although it may not look like a big deal, it is a very impressive tracemaker, deserving the rapt attention of geologists and paleontologists. (Photograph taken by Anthony Martin.)

So you’re probably wondering why geologists and paleontologists should hear about gopher tortoises from me. It’s a good question, because I’m not a biologist, and these animals are famous for their very important role in ecosystems. Specifically, they are well known as keystone species in the sandy soils of longleaf pine-wiregrass communities of the southeastern U.S. Just like the keystone to a building, once you remove gopher tortoises from their ecosystems, a lot of other species disappear with it. Surprisingly, their ecological worth all revolves around their burrows.

And oh, what marvelous and grandiose burrows they make! The lengthiest of their measured burrows approach 14 meters (45 feet) long and as much as 6 meters (20 feet) vertically below the ground surface. These burrows commonly twist to the right or left on their way down, which probably helps protect its tortoise occupant against predators, while maintaining a constant temperature and humidity in the burrow. With so much digging, of course, a lot of sand has to be excavated, so the locations of their burrows are easily spotted by looking for piles of sand in the middle of a grassy field or in a longleaf-pine forest. For female tortoises, these sand piles also serve as nesting sites, where they bury their eggs to incubate.

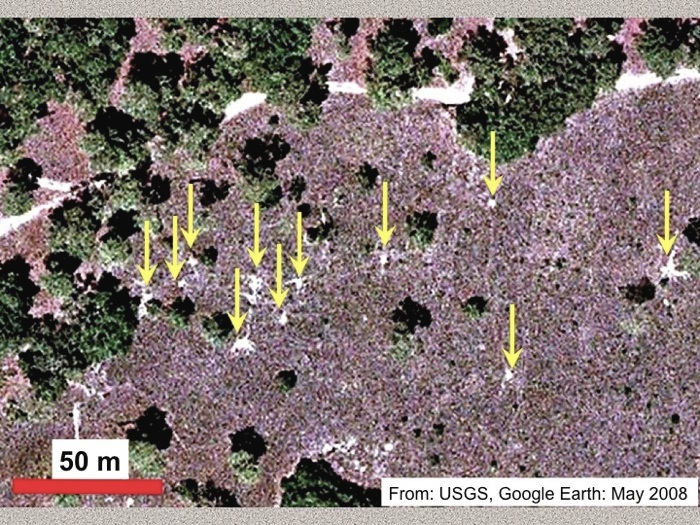

Satellite view of gopher-tortoise burrows on St. Catherines Island, Georgia. Nearly all of the white spots you see in the photo – indicated by the yellow arrows – are the sand piles (aprons) outside of their burrows. Look closely, and you can see some of the trails worn down by tortoises traveling between burrows. Yes, these are animal traces you can see from space! (Original image from the U.S. Geological Survey and Google Earth, taken in May 2008.)

Satellite view of gopher-tortoise burrows on St. Catherines Island, Georgia. Nearly all of the white spots you see in the photo – indicated by the yellow arrows – are the sand piles (aprons) outside of their burrows. Look closely, and you can see some of the trails worn down by tortoises traveling between burrows. Yes, these are animal traces you can see from space! (Original image from the U.S. Geological Survey and Google Earth, taken in May 2008.)

Close-up view of a sand apron outside of a gopher-tortoise burrow entrance. The large amount of sand tells you that this must be a very deep burrow. Field notebook is about 15 cm (6 in) long. (Photograph taken by Anthony Martin on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Close-up view of a sand apron outside of a gopher-tortoise burrow entrance. The large amount of sand tells you that this must be a very deep burrow. Field notebook is about 15 cm (6 in) long. (Photograph taken by Anthony Martin on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

In cross-section, their burrows have flat bottoms and rounded tops, similar to a tortoise body. Burrow widths varies with the length of the tortoise, as it needs to be wide enough for the tortoise to turn around in the burrow. So this means a 30-cm (12 in) wide burrow can accommodate a tortoise of that length or less. The powerful front limbs of tortoises are specially adapted for digging, ending in flat, spade-like feet with stout claws. Burrow walls are compacted by the hard shell of the tortoise as it moves up and down the burrow. These burrows descend steeply, at angles of 20-40°, which means they have to be good climbers to get out of their deep burrows.

Down-tunnel view of a gopher-tortoise burrow, with the light at the end of that tunnel not from an oncoming train, but reflected morning sunlight on the tunnel wall at one of its turns. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Down-tunnel view of a gopher-tortoise burrow, with the light at the end of that tunnel not from an oncoming train, but reflected morning sunlight on the tunnel wall at one of its turns. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

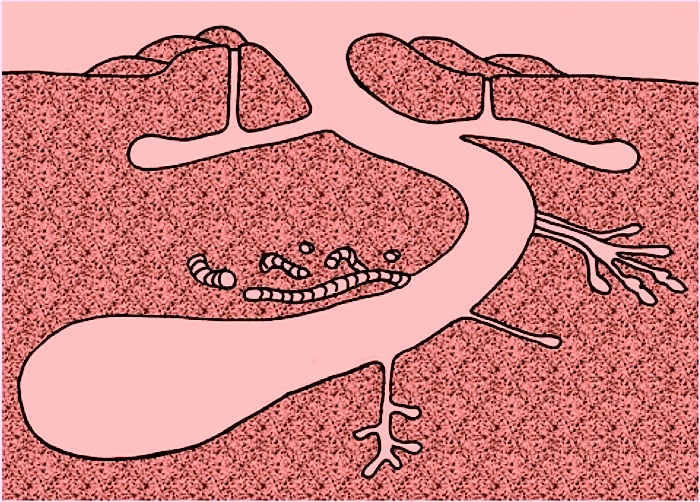

Now think about a tunnel that’s about 10 m (33 ft) long and 30 cm (12 in) wide, and how much space that represents underneath the ground, and you’ll see what I mean about the vital role of these burrows ecologically, geologically, and (most importantly) ichnologically. In terms of ecology, about 200-300 species of invertebrate and vertebrate animals cohabit these burrows (whether a gopher tortoise is in it or not), including the longest snake in North America, the eastern indigo snake (Drymarchon couperi), the secretive gopher frog (Rana capito), the Florida mouse (Podomys floridanus), and a bunch of different insects. At least a few of the insects and the Florida mice make their own burrows, thus adding their little homes to the main burrow, like small anterooms to a big mansion.

Idealized conceptual sketch showing a cut-away view through a gopher-tortoise burrow with many additional burrows made by other animal species. Note especially the short horizontal tunnels near the burrow top, which would have been made by hatchling tortoises, and the vertical shafts that connect to these, which would have been made by Florida mice. (Illustration by Anthony Martin.)

Idealized conceptual sketch showing a cut-away view through a gopher-tortoise burrow with many additional burrows made by other animal species. Note especially the short horizontal tunnels near the burrow top, which would have been made by hatchling tortoises, and the vertical shafts that connect to these, which would have been made by Florida mice. (Illustration by Anthony Martin.)

So now you can see why this ichnologist (that would be me) became rather enamored with these burrows. For one thing, they have great preservation potential in the fossil record. A general rule in ichnology for the preservation of burrows is “deeper is better,” in that burrows that go to great depths are less likely to be eroded by surface weathering and erosion, and more likely to be fossilized. Secondly, we know that vertebrate animals in the geologic past also made big burrows, such as synapsids and even small dinosaurs. I’ve done research on the few dinosaur burrows interpreted from the geologic record, and am especially interested in how such large burrows might compare with similar burrows made by modern animals, such as gopher tortoises.

But how to study these burrows without digging them out and leaving the tortoises undisturbed? Fortunately, two colleagues of mine at Georgia Southern University – Sheldon Skaggs and Robert (Kelly) Vance – came up with an elegant solution, which was to use ground-penetrating radar, also known by its acronym of GPR. This method uses a portable unit to transmit microwaves underground (don’t worry, not these aren’t intense enough to cook the tortoises), which reflect off surfaces with different qualities, especially the curved, compacted surfaces of burrow walls. Computers then process and render these reflections into three-dimensional images that more-or-less represent the forms and geometries of the burrows.

Sure enough, we tried out this technique on gopher-tortoise burrows on St. Catherines Island of the Georgia coast in January and July this year. Although we can’t share all of our results just yet, we did successfully make three-dimensional images of the burrows, all without us having to burrow ourselves, or bother the tortoises by becoming homewreckers. Veronica Greco, a wildlife biologist on St. Catherines Island who has studied the behavior and breeding of the tortoises, also helped us to better understand the biology of these reptiles.

Although it looks like Sheldon (center) is mowing the lawn and I’m (right) just supervising, he’s actually pushing a portable ground-penetrating radar (GPR) unit over a field that has some gopher-tortoise burrows in it, while I walk alongside to look at the reflection profiles. Kelly (background) is no doubt monitoring our every move, but is also recording our location. (Photograph by Ruth Schowalter, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Although it looks like Sheldon (center) is mowing the lawn and I’m (right) just supervising, he’s actually pushing a portable ground-penetrating radar (GPR) unit over a field that has some gopher-tortoise burrows in it, while I walk alongside to look at the reflection profiles. Kelly (background) is no doubt monitoring our every move, but is also recording our location. (Photograph by Ruth Schowalter, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

My talk at the GSA meeting will be about how we used GPR to study the burrows in a non-invasive way, and how our results might be applied to studying similar burrows in the fossil record. After the meeting is over, we plan to summarize our results in a research article, which we’ll submit to a journal later this year for peer review.

Unfortunately, gopher tortoises are endangered because of huge losses in acreage of longleaf-pine forests in the southeastern U.S. during the past 200 years or so. Knowing this makes our study of their burrows even more meaningful, for if these wonderful tracemakers go extinct in the near future, we will not have the chance to study them and their burrows. In this sense then, only geologists and paleontologists who know about their ichnology through studies like ours will be able to study their burrows, which would be a sad thing indeed. Let’s hope they survive and thrive, and we can continue to learn more about these superb burrowing animals and their traces.

(P.S. Many thanks to the St. Catherines Island Foundation for their support of our research!)

Further Reading

Aresco, M.J., 1999. Habitat structures associated with juvenile gopher tortoise burrows on pine plantations in Alabama. Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 3: 507-509.

Doonan, T.J., and Stout, I.J., 1994. Effects of gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) body size on burrow structure. American Midland Naturalist, 131: 273-280.

Epperson, D.M., and Heise, C.D., 2003. Nesting and hatchling ecology of gopher tortoises (Gopherus polyphemus) in southern Mississippi. Journal of Herpetology, 37: 315-324.

Guyer, C., and Hermann, S.M. 1997. Patterns of size and longevity for gopher tortoise burrows: implications for the longleaf pine-wiregrass ecosystem. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America, 78: 254.

Jackson, D.R. and Milstrey, E.R. 1989. The fauna of gopher tortoise burrows. In Diemer, J.E. (editor), Proceedings of the Gopher Tortoise Relocation Symposium, State of Florida, Game and Freshwater Fish Commission, Tallahassee, Florida: 86-98.

Jones, C.A., and Franz, R. 1990. Use of gopher tortoise burrows by Florida mice (Podomys floridanus) in Putnam County, Florida. Florida Field Naturalist, 18: 45-68.

Lips, K.R. 1991. Vertebrates associated with tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) burrows in four habitats in south central Florida. Journal of Herpetology, 25: 477-481.

Martin, A.J., Skaggs, S.A., Vance, R.K., and Greco, V. 2011. Ground-penetrating radar investigation of gopher-tortoise burrows: refining the characterization of modern vertebrate burrows and associated commensal traces. Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, 43(5): 381.

Varricchio, D.J., Martin, A.J., and Katsura, Y. 2007. First trace and body fossil evidence of a burrowing, denning dinosaur. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, B, 274: 1361-1368.

Witz, B.W., and Wilson, D.S., and Palmer, M.D. 1991. Distribution of Gopherus polyphemus and its vertebrate symbionts in three burrow categories. American Midland Naturalist, 126: 152-158.