I first became a scientist in my backyard. This path to life-long inquiry began when I was four years old, as soon as my family moved to a larger house, and one with a larger yard. This small, outdoor patch of land with a few large trees, bushes, and grass soon became my field area, laboratory, classroom, and all-purpose place for conducting experiments in nature. Even better, my proclivity for observing this world outside of myself was encouraged – or at least tolerated – by my mother and father.

At the time, I had no idea just how important of a role this backyard and parental support would play in my scientific career. Yet now I look back on it with a mix of gratitude and wistfulness, especially as both of my parents have departed this earth I have studied for most of my life.

Here’s where I first learned science by going into the field. Back in the day, people – including my parents – called it a “backyard.” (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Here’s where I first learned science by going into the field. Back in the day, people – including my parents – called it a “backyard.” (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Indiana was an odd place for a natural scientist to develop in the 1960s. I recall how kids in public schools there and then were encouraged to study and pursue careers in science. However, this was mostly because of the “space race,” in which the U.S. was competing against the U.S.S.R. to see who could first land on the moon. I loved space, staring at the moon, planets, and stars, and I watched Star Trek (the original series, of course), dreaming of some day traveling in space. Science fiction stories became an outlet for me as well. Weekly trips to the public library meant checking out books by Arthur C. Clarke, Ray Bradbury, and other sci-fi writers who expanded my perspectives and kick-started my imagination with worlds far different from those I could experience in the Midwest.

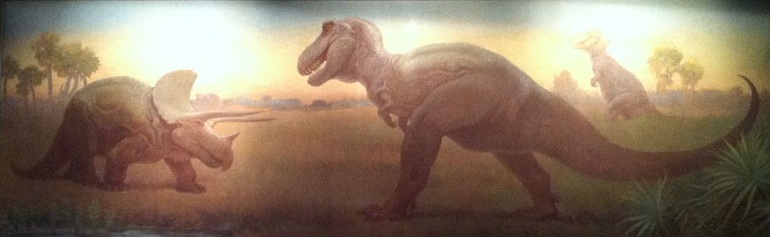

Yet science fiction wasn’t the only subject that put me on a first-name basis with librarians as I checked out stacks of books. There were two other topics that supplemented my learning, namely dinosaurs and insects. Although the study of dinosaurs had not yet gone through its major scientific revolution of the 1970s, these animals still loomed large in my and other children’s inner worlds. “Tyrannosaurus rex! Stegosaurus! Brontosaurus!” we kids would shout gleefully at one another, or at bemused adults. Books with artistic recreations of dinosaurs and the occasional movie starring dinosaurian protagonists – such as The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, The Valley of Gwangi – fed our fancy, too.

Photo of the original mural of Charles Knight’s ‘Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus‘ (1927), which is in the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois. While growing up, I saw this image many times in books, and it inspired both my artistic and scientific leanings. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Photo of the original mural of Charles Knight’s ‘Triceratops and Tyrannosaurus‘ (1927), which is in the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois. While growing up, I saw this image many times in books, and it inspired both my artistic and scientific leanings. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Still, no matter how hard I imagined, I could not see a tyrannosaur in my backyard, let alone watch it stalk and devour its prey. In contrast, insects and other animals with jointed legs delivered Tennyson’s “nature red in tooth and claw,” and much more. For about nine months of any given year during my childhood, starting in the spring, I could step out the back door of my house and watch ants, bees, wasps, butterflies, moths, spiders, and praying mantises. Plant-insect interactions in particular – such as pollination, herbivory, and wound responses in plants – drew me in, teaching me those ecological principles long before I ever heard the words “pollination,” “herbivory,” and “wound response.”

Roses blooming in the front yard of my Indiana home in August 2014, attracting a pollen-gathering carpenter bee (probably Xylocopa virginica). Female carpenter bees leave exquisitely crafted traces in wood, boring into them to make brooding cells, which they provision with pollen balls. The rose bush was originally planted by my father in the late 1970s. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Roses blooming in the front yard of my Indiana home in August 2014, attracting a pollen-gathering carpenter bee (probably Xylocopa virginica). Female carpenter bees leave exquisitely crafted traces in wood, boring into them to make brooding cells, which they provision with pollen balls. The rose bush was originally planted by my father in the late 1970s. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Insect damage on the leaf of an apple tree in the backyard of my Indiana home in August 2014. The leaf mine (left) was probably caused by a different insect from the one that made the incision along the leaf margin just to its right. Notice the brown discoloration in the leaf, a trace of its response to these injuries and its healing. My father planted this apple tree, but I’m not sure when: maybe also in the late 1970s. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Insect damage on the leaf of an apple tree in the backyard of my Indiana home in August 2014. The leaf mine (left) was probably caused by a different insect from the one that made the incision along the leaf margin just to its right. Notice the brown discoloration in the leaf, a trace of its response to these injuries and its healing. My father planted this apple tree, but I’m not sure when: maybe also in the late 1970s. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Predation fascinated me, probably because death was such an inappropriate topic for children to discuss with their parents. This wasn’t the artificial, acted-out stuff of TV and movies, but was in your face, or rather, in front of your face. With mild shame now (and apologies to my Buddhist friends), I remember going into my backyard, picking up ants, and throwing them into wolf spiders’ ground webs. It was a repeatable experiment in which I could observe spider response-times to tactile stimuli, and it was real.

My backyard is also where I learned to sit still and wait. As soon as I spotted a praying mantis, it was only a matter of time before that magnificent, big-eyed head swiveled to lock onto a target, moved delicately toward it, and sprang its barbed arms forward to snatch and hold its squirming dinner, which it devoured alive. Who the hell needed TV, with sharks, lions, and polar bears, when you had this, and for free?

Ah, there’s that word, “free.” This connects to the main reason why my science leaned more toward field observations and less to indoor labs, a legacy that stuck. You see, my family was poor. I didn’t know this until other kids at school made fun of my shoes, which had holes in their soles, or my pants, which were too outgrown or ragged, or my haircuts, which looked odd because my mother cut it, and badly, but with good intentions, because haircuts done by barbers were just too expensive. Compounding this (and not coincidentally), my mother and father never went to college, and my parents struggled to maintain their traditional roles, for which they were ill suited to succeed.

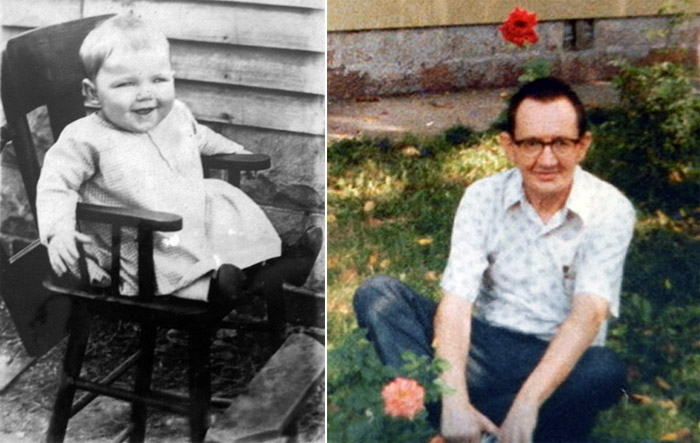

My father was a veteran of World-War II, and late in his shortened life was diagnosed with PTSD (post-traumatic stress syndrome), which in the 1970s was labeled “shell shock.” This condition meshed all too well with his alcoholism, meaning he had trouble keeping down a job for more than a few years. His last paycheck came from working as a night-shift janitor at a Columbia Records distribution center in Terre Haute. This job ended once he began suffering from a series of serious illnesses that put him in and out of hospitals for the last 15 years of his life. Only 59 years old, he died in the summer of 1985, just a few months before I left for Ph.D. study at the University of Georgia.

My father at six months old (in 1927) and near the end of his life (circa 1982). His mother was still alive when the photo at the left was taken, but he never got to know her; she died when he was only two years old. During his last ten years of life, he developed a fondness for roses, cultivating them in our yard and bringing beauty to our home every year.

My father at six months old (in 1927) and near the end of his life (circa 1982). His mother was still alive when the photo at the left was taken, but he never got to know her; she died when he was only two years old. During his last ten years of life, he developed a fondness for roses, cultivating them in our yard and bringing beauty to our home every year.

My parents were also Catholic, which in their time meant the only birth control they used was prayer. As a result, we had a big family, and I grew up with four brothers and one sister. But we were also reminded of unseen siblings, the ones who might have been. My mother was pregnant 13 times, with six successful births, but also six miscarriages and one stillbirth, meaning she bore more deaths than lives. Much later, I realized how this must have placed a profound emotional burden on her, even though she almost never mentioned it.

Judging from my mother’s affection for books and reading, I think she wanted to be an intellectual of sorts, perhaps even a scientist, or at least she wanted to learn and debate ideas with other people. This, however, was not possible when cleaning, cooking, shopping, paying bills, and otherwise taking care of six kids, all while constantly pregnant until she had her last child in 1962. Add to those demands a chain-smoking, alcohol-fueled, and narrow-minded husband who helped with none of those household tasks, followed by her being his in-house nurse and servant during the last 15 years of his life, and she didn’t stand a chance of reaching those ideals.

Happier times for my parents, soon after my father came home after his service in the U.S. Army during World War II, where he fought in the Pacific. It would be his only trip abroad, but it scarred him for the rest of his life, which affected everyone around him. My mother never traveled outside of the U.S. and stayed in the Midwest for nearly all of her life.

Happier times for my parents, soon after my father came home after his service in the U.S. Army during World War II, where he fought in the Pacific. It would be his only trip abroad, but it scarred him for the rest of his life, which affected everyone around him. My mother never traveled outside of the U.S. and stayed in the Midwest for nearly all of her life.

Given such a family history, I experienced class differences and situations in college and graduate school that perplexed and occasionally stung. Even now, despite having taught at an elite private university for nearly 25 years, I still wrestle with imposter syndrome, and with how much my background sets me apart from others in my rarified academic world.

For instance, many of my academic colleagues are second-generation academics, or otherwise come from more socially elevated or well-to-do (or at least middle-class) families, where they never had to worry about paying the bills in time and making it through the month. Moreover, most of the students I’ve taught over the years have almost never experienced such economic anxieties, either. Behind all of the science I do and teach, and all of my achievements, I still hold onto a nagging, debilitating fear of scarcity, and a secret shame of how my family was on welfare and used food stamps to buy groceries. The taste of government cheese still lingers.

In the 1960s, education seemed like a way to escape from the cycle of poverty, and that was the message I constantly received from my mother and father. Sadly, that message sometimes translated as, “Don’t be failures like us.” Later in life, I turned that little frown upside down when I traveled, met wonderful people, and made scientific discoveries, many of which happened whenever I did field work in places far away from that backyard in Indiana.

In grade school music class, I used to get in trouble for singing the chorus of Waltzing Matilda a bit too boisterously, which happened in between reading books about dinosaurs and insects. About 40 years later, I was walking along the coast of Victoria, Australia, looking for dinosaur tracks and insect trace fossils in the Cretaceous rocks there. Funny how that happens sometimes. (Photo by Ruth Schowalter.)

In grade school music class, I used to get in trouble for singing the chorus of Waltzing Matilda a bit too boisterously, which happened in between reading books about dinosaurs and insects. About 40 years later, I was walking along the coast of Victoria, Australia, looking for dinosaur tracks and insect trace fossils in the Cretaceous rocks there. Funny how that happens sometimes. (Photo by Ruth Schowalter.)

But here’s the thing about that whole “education helps people to escape from poverty” trope, one seemingly affirmed by my little personal story. This was much easier to do in the 1960s than today. The gap between the poor and rich in the U.S. today is the worst it’s been since the 1920s, with no sign of abating. People who wants to preach their faith-based mantra of “People just need to work harder to succeed” conveniently overlook that Horatio Alger was a second-generation Harvard man and Ayn Rand took government assistance. Also, an increased emphasis on student loans to pay for exploding tuition rates during the past 30 years has meant young, aspiring scientists may be starting their careers with crippling debt.

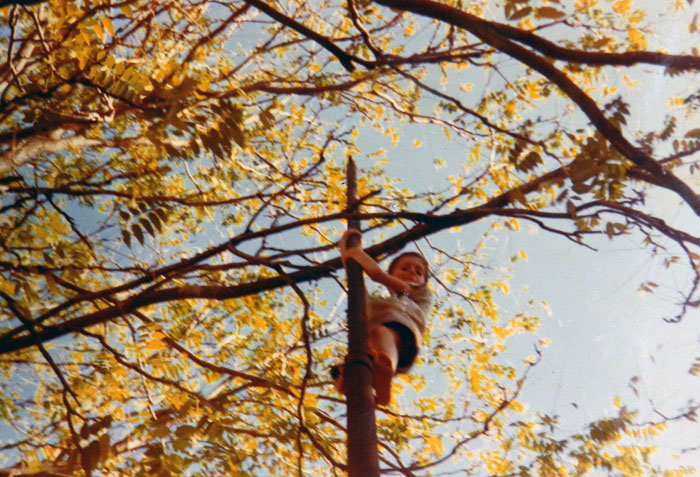

But here’s another thing: I was damned lucky because of my parents. Not despite them, but because of them. That’s what I say – and with considerable ferocity – every time someone tries to tell me (in a well-meaning way) how much my life reflects “the American dream.” For one thing, I grew up at a time when white boys were far more encouraged to go into science than African-American boys, or all girls. This accident of being born male, and in a family belonging to the dominant ethnic group of my culture, meant I benefited from the privilege of my gender and race, even as my socioeconomic background held me back.

That’s me, climbing a flagpole just outside my house when I was about seven years old, circa 1967. The rest of my family was standing below watching, cheering me on, and documenting the event. Little did I know at the time that other kids were told they couldn’t climb flagpoles, let alone make it to the top. Yes, that’s a metaphor. (P.S. The flagpole’s gone now.)

That’s me, climbing a flagpole just outside my house when I was about seven years old, circa 1967. The rest of my family was standing below watching, cheering me on, and documenting the event. Little did I know at the time that other kids were told they couldn’t climb flagpoles, let alone make it to the top. Yes, that’s a metaphor. (P.S. The flagpole’s gone now.)

I also had lots of help along the way, such as financial aid and scholarships in college, and teaching assistantships in graduate school. This meant I didn’t have to take out student loans. Sure, I had less than $100 to my name the first month I began the teaching job I still hold (so far), but at least I began that job debt-free. Many of today’s aspiring scientists don’t have this luxury, and entrenched inequities related to gender and ethnicity continue to discourage careers in science for most Americans. Also, achieving a college degree today is nine times more likely if you come from an upper-income family than a poor one. It was never easy for poor people to become successful scientists, but it’s far, far tougher today. I was lucky.

Perhaps most importantly, though, I had parents who let me play outside and supported my learning science, however weird I must have seemed to them. I mean, staying out in the backyard for hours, flinging ants in spider webs, and watching praying mantises kill other insects? That was pretty strange, even in the 1960s. I even climbed trees in our backyard. I suspect that many of today’s “helicopter parents” would have forbidden a scrawny runt like me from going outside, let alone get my face close to spiders and insects, and handle unknown plants. Climbing trees probably would have involved first donning a series of ropes, carabiners, harnesses, padding, and a helmet, all while being supervised by a team of tree-climbing experts. Instead, like any arboreal primate should, I climbed those trees by myself, occasionally fell out of them, then got back up and climbed again. I was lucky.

My favorite climbing tree in my backyard, which I started scaling when I was about six years old, so it must be more than 70 years old now. It was great fun to see how far I could get up into it and explore, and I found much peace just sitting in its crooks, watching the world below. Notice in the close-up (right) all of the scars on the trunk, marking the sites of the low-hanging branches, which fell off the tree a long time ago. (Yes, that’s another metaphor.)

My favorite climbing tree in my backyard, which I started scaling when I was about six years old, so it must be more than 70 years old now. It was great fun to see how far I could get up into it and explore, and I found much peace just sitting in its crooks, watching the world below. Notice in the close-up (right) all of the scars on the trunk, marking the sites of the low-hanging branches, which fell off the tree a long time ago. (Yes, that’s another metaphor.)

My parents also regularly took me to our modest public library, where I checked out many books, which I read, and sometimes re-read. After my grade-school teachers alerted them that I was showing talent as an artist, my parents also spent some of their meager cash to buy me crayons, pencils, paper, acrylic paints, oil paints, and canvases as birthday and Christmas presents. So I drew and painted, and nature was my inspiration for such creations. I still can draw well – and sometimes teach drawing to my students – because of what my parents did for me. I was lucky.

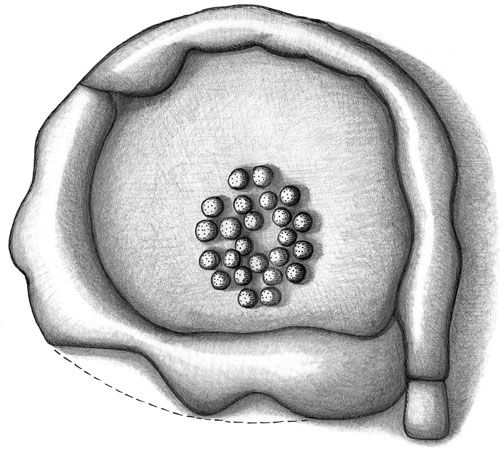

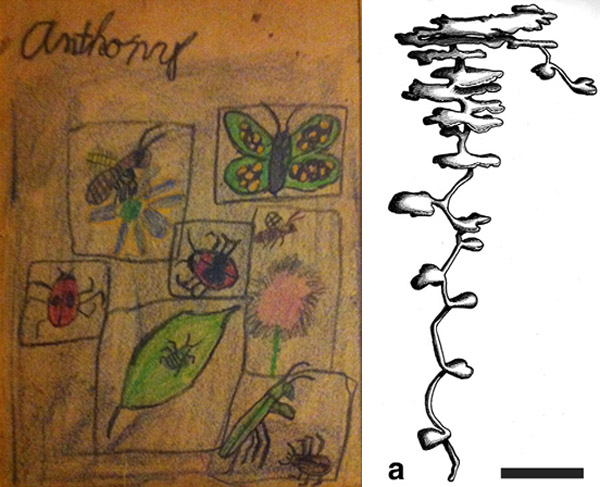

One of my earliest attempts at scientific illustration (left), coupled with one of my more recent efforts (right). The one on the left – clearly intended as a multi-part figure – shows some of the insects I observed in my backyard, as well as some of the ecological interactions they had as pollinators, predators, and prey. The one on the right is from Figure 5.4a in Life Traces of the Georgia Coast (2013, Indiana University Press, p. 192), and is the subsurface form of a nest made by Florida harvester-ants (Pogonomyrmex badius); scale bar = 25 cm (10 in).

One of my earliest attempts at scientific illustration (left), coupled with one of my more recent efforts (right). The one on the left – clearly intended as a multi-part figure – shows some of the insects I observed in my backyard, as well as some of the ecological interactions they had as pollinators, predators, and prey. The one on the right is from Figure 5.4a in Life Traces of the Georgia Coast (2013, Indiana University Press, p. 192), and is the subsurface form of a nest made by Florida harvester-ants (Pogonomyrmex badius); scale bar = 25 cm (10 in).

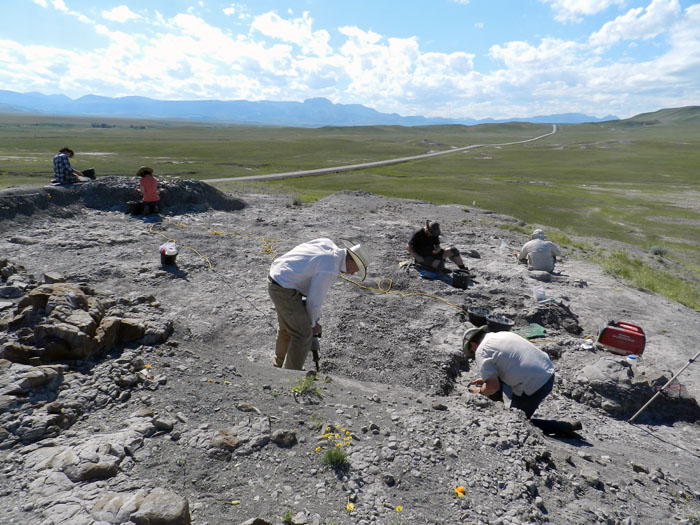

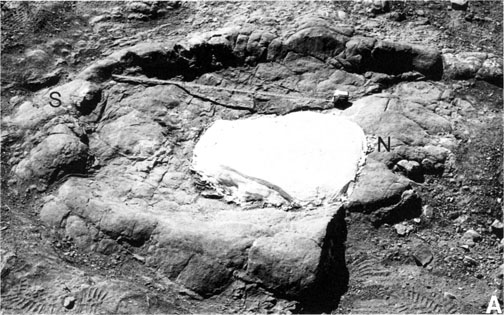

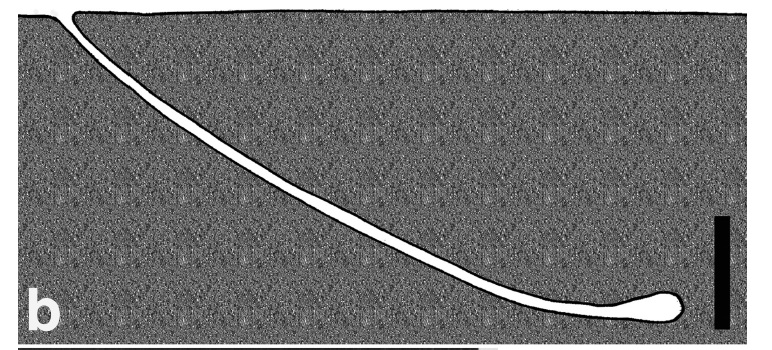

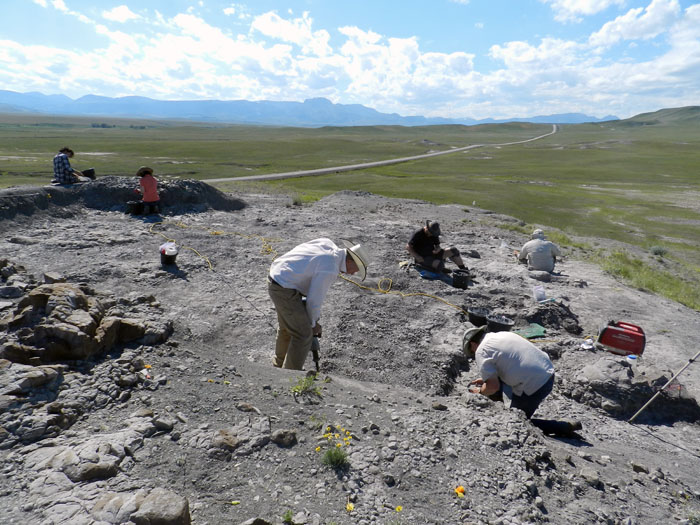

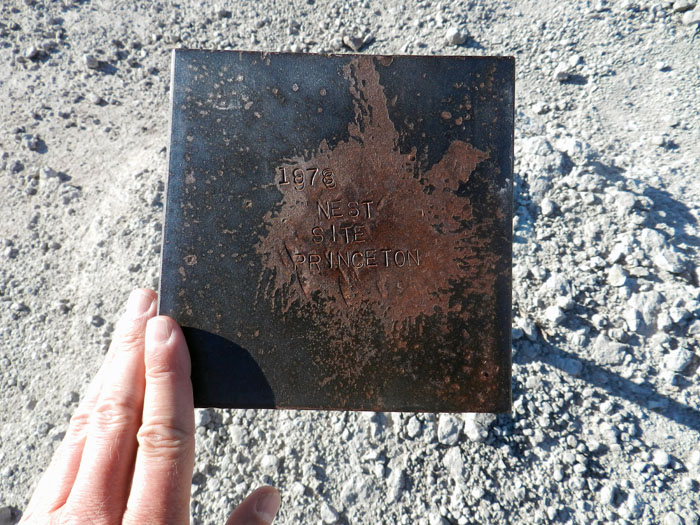

As I do field work today, I silently thank my father for taking me on hunting and fishing trips, effectively planting the seeds for my present-day comfort with forests, streams, lakes, and other outdoor environments. On those hunting trips, I learned what little my father knew then about tracking animals, a skill that I honed later in life, and now one of my passions. On fishing trips, I watched the behavior and ecology of freshwater crayfish, which abounded in the streams of southern Indiana. I had no clue that more than 40 years later I would reconnect with that childhood interest in crayfish by discovering the oldest fossil crayfish in Australia. I also did a different kind of fishing by studying and interpreting fish trace fossils, such as a trail left by a bottom-feeding fish about 50 million years ago in Wyoming. Then I combined my childhood love of insects and dinosaurs by writing and publishing a paper about Cretaceous insect cocoons near dinosaur nests in Montana. I didn’t see an ocean until I was 20 years old, but last year published a 700-page book, Life Traces of the Georgia Coast, which I also illustrated myself. None of those things would have happened without my parents’ help early in my life. I was lucky.

My father and mother did what they could with what life dealt them, and my mother in particular. She was born in northern Illinois and lived there through the Great Depression during her childhood. While there, she met her high-school sweetheart, who some day would be the father of her six children. He went off to fight in a world war, she waited for him to return, and they married soon afterwards. They headed south to Terre Haute, and lived in one house, then another. The latter was her home for 50 years.

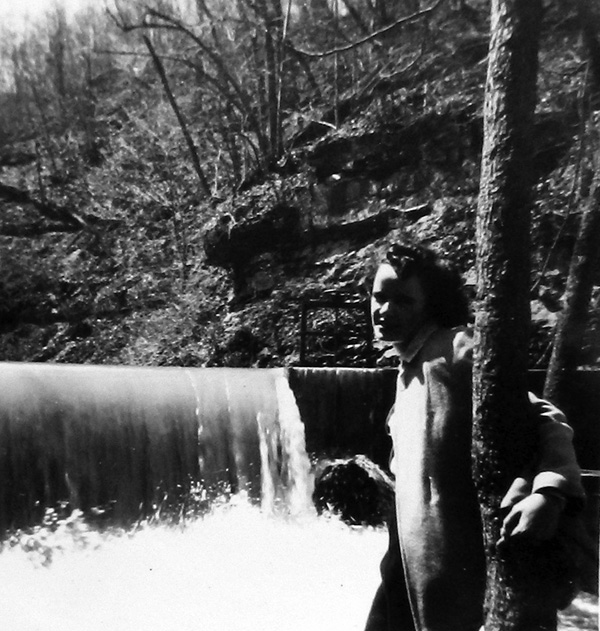

My mother on her honeymoon at Turkey Run State Park in southern Indiana, 1947. While looking through a photo album in 2012, I was delighted to see this photo, showing her when she was fully in love with my father, but also enjoying what must have been a glorious waterfall. Best of all for me, though, it has an outcrop of Late Carboniferous (Pennsylvanian) Period deltaic sandstones in the background.

My mother on her honeymoon at Turkey Run State Park in southern Indiana, 1947. While looking through a photo album in 2012, I was delighted to see this photo, showing her when she was fully in love with my father, but also enjoying what must have been a glorious waterfall. Best of all for me, though, it has an outcrop of Late Carboniferous (Pennsylvanian) Period deltaic sandstones in the background.

My mother outlived my father by nearly 30 years and got to see how her love of books, reading, and encouragement of my learning came back home to her. In 2001 and 2006, it was with much pride I mailed her each edition of a textbook I wrote and published (Introduction to the Study of Dinosaurs). In the preface to Life Traces of the Georgia Coast, I pointedly thanked her and my father for cultivating a childhood life filled with books, art, and the outdoors.

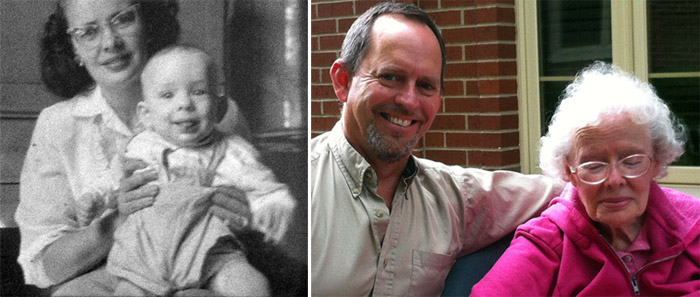

The first and last photographs of my mother, when she was three years old (about 1929) and just last month, the latter photo taken by my brother Pat.

The first and last photographs of my mother, when she was three years old (about 1929) and just last month, the latter photo taken by my brother Pat.

My mother died three weeks ago. The first stroke was toward the end of December 2013, and its treatment necessitated her going to a hospital, and then to assisted care. For the next eight months, she had a picture window that looked out onto a courtyard, where she watched the blooms, butterflies, and birds of what would be her last Indiana spring and summer. On August 26, she had a second and more deadly stroke, putting her in a coma that took away all of her speech, thoughts, and memories. After receiving emergency care in Terre Haute, she was evacuated by helicopter to an intensive-care unit in Indianapolis that same night. Six days later, she exhaled for the last time, less than a week shy of her 88th birthday.

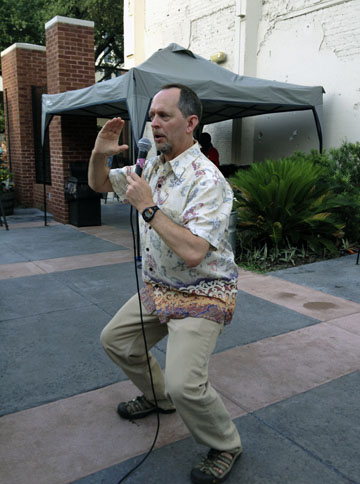

Me giving a talk about my most recent book, Dinosaurs Without Bones (2014) at the Decatur Book Festival last month. At the end of my talk, I dedicated it to my mother. Almost no one in the audience knew she was in a coma at the time, and none of us knew she would die three days later. (Photo by Ruth Schowalter.)

Me giving a talk about my most recent book, Dinosaurs Without Bones (2014) at the Decatur Book Festival last month. At the end of my talk, I dedicated it to my mother. Almost no one in the audience knew she was in a coma at the time, and none of us knew she would die three days later. (Photo by Ruth Schowalter.)

Just before this second stroke, I flew up to Indiana to see her, and we spent some time with our extended family, but also some quiet moments talking together, just mother and son. During this visit, I told her how much I appreciated everything she had done for me. We got to say goodbye to one another. We were lucky.

Today I am a trace of my mother’s and father’s love and care, and a trace of my home and backyard in Terre Haute, Indiana. Given more luck, I’ll be around for a while longer, leaving more traces of my own, and in many more places. Thank you, Dad. Thank you, Mom. You did good.

First and last photos of my mother with me, separated by more than 50 years. As you can see from both pictures, my disposition hasn’t changed much. And thanks to Mom, it probably won’t.

First and last photos of my mother with me, separated by more than 50 years. As you can see from both pictures, my disposition hasn’t changed much. And thanks to Mom, it probably won’t.

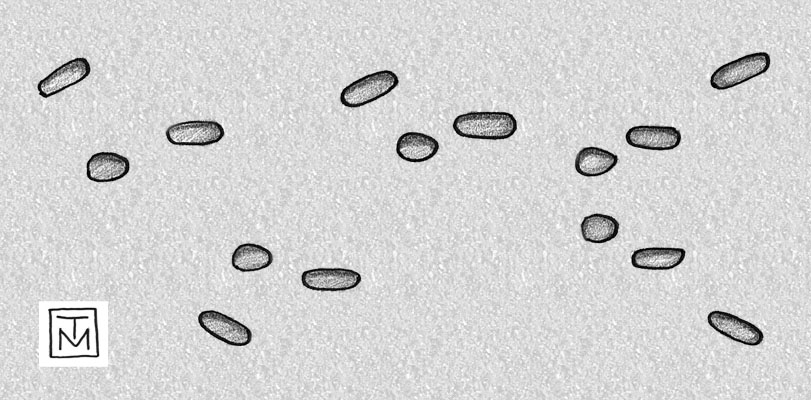

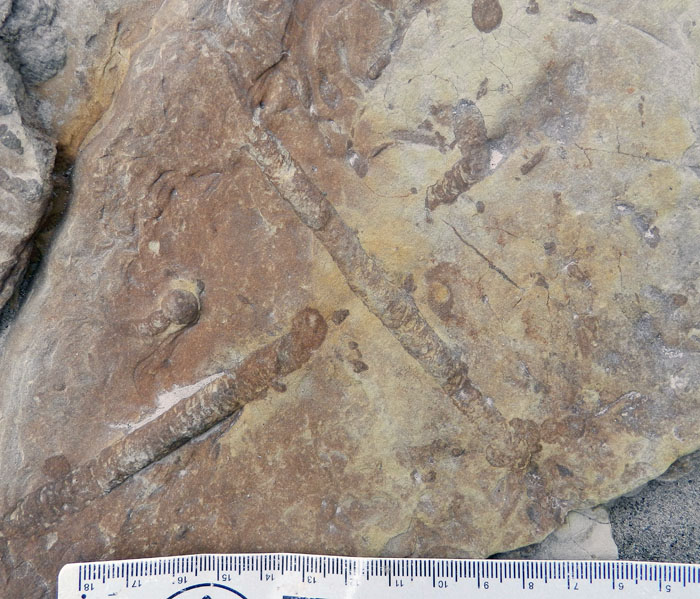

You’ve heard of ‘Field of Dreams’? This is a ‘Field of Feces.’ The ground here is adorned with dinosaur coprolites, which are weathering out of the mudstone and breaking apart on the surface. This serves as a good example of how once you know what the dinosaur coprolites look like in this area, you’re less likely to just walk by them, singing “Where Have All the Coprolites Gone?”. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

You’ve heard of ‘Field of Dreams’? This is a ‘Field of Feces.’ The ground here is adorned with dinosaur coprolites, which are weathering out of the mudstone and breaking apart on the surface. This serves as a good example of how once you know what the dinosaur coprolites look like in this area, you’re less likely to just walk by them, singing “Where Have All the Coprolites Gone?”. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)