Every paleontologist has a Dolf story. Or at least it seems that way, especially for the past couple of weeks. One-by-one, like feather-duster worms poking their heads out of burrows, these stories have all emerged since the paleontological community heard the sad news that Adolf (Dolf) Seilacher died on April 26, 2014.

This manifestation of Dolf connecting with so many paleontologists over multiple generations symbolizes his ultimate and most lasting trace as a scientist and teacher. During his 89 years with us, he observed, discovered, pondered, argued, and argued more over the evidence that life left in the rocks of the past 600 million years or so. Much of this evidence is preserved as trace fossils, the vestiges of animal behavior that imparted their former presence as burrows, trails, tracks, feces, or other signs of life that almost never connect to their undoubted makers. Although Dolf was no slouch when pontificating on the bodily remains of ancient animals, either, it was with trace fossils where he truly excelled.

Adolf (“Dolf”) Seilacher in his natural habitat, teaching students and professors alike when in the field. Notice how he was using paper and pencil as tools, which were instrinsic to his teaching methods. (Photo taken by Anthony Martin at Ringgold, Georgia in November 1997; Dr. Sally Walker (right) for scale.)

Adolf (“Dolf”) Seilacher in his natural habitat, teaching students and professors alike when in the field. Notice how he was using paper and pencil as tools, which were instrinsic to his teaching methods. (Photo taken by Anthony Martin at Ringgold, Georgia in November 1997; Dr. Sally Walker (right) for scale.)

Dolf is often acknowledged as the founder of modern ichnology, the study of traces and trace fossils. Through this science, he could divine the original intents and purposes of trilobites, worms, clams, snails, shrimp, fish, pelycosaurs, dinosaurs, and many other former denizens of the earth. He accomplished this Sherlockian feat through the careful examination of ancient animals’ signatures, or the jots and tittles in those signatures: miniscule clues he reconstructed as entire manuscripts or symphonies that spill their secrets to those who pay heed. Dolf’s marvelous ability to spin fossil gold from carbonized straw is most of what inspired the many stories we paleontologists tell about him, although his personality was intrinsically linked to this, too (more on that later).

Nonetheless, what was truly remarkable about how Dolf worked his ichnological magic was his use of such old-fashioned methods. What were his primary tools for observing? His eyes, brain, pencil, paper, and drawing: no laser scanners (let alone “laser cowboys”), CT imaging, digital photogrammetry, rotating 3-D visualizations, or other modern technological tools were necessary for what he did. If someone had a time machine, they could have inserted Dolf into the late 19th century among the naturalists of those days, and he would have blended. Paradoxically, though, we 21st century paleontologists remember him as someone who surpassed all of us with his observational and intuitive skills. In this sense, he was a reminder of the readily available and valuable means we already possess that allow us to make sense of our planet and its vast history.

The Hand of Dolf, drawing onto a Middle Jurassic trace fossil (Zoophycos) to teach me and others how it was made by worm-like animal on a deep seafloor about 170 million years ago. (Photograph taken by Anthony Martin in Switzerland, 2003.)

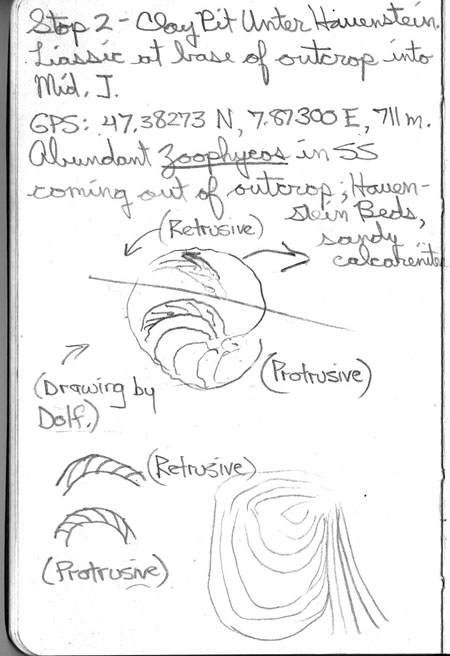

A composite trace (drawings plus writings) made by Dolf and me. The central figure is a visual explanation he drew for me, showing how one could figure out whether the Zoophycos-making animal was moving down below the sediment surface (protrusive) or moving up (retrusive) as it burrowed. Under his watchful eye, I then parceled out the details below. Field notes and drawings done on July 16, 2003, at the outcrop indicated in Switzerland.

A composite trace (drawings plus writings) made by Dolf and me. The central figure is a visual explanation he drew for me, showing how one could figure out whether the Zoophycos-making animal was moving down below the sediment surface (protrusive) or moving up (retrusive) as it burrowed. Under his watchful eye, I then parceled out the details below. Field notes and drawings done on July 16, 2003, at the outcrop indicated in Switzerland.

Still, Dolf vigorously disagreed whenever anyone praised him as an “artist,” insisting he was a mere illustrator. With all due respect to his memory, he was wrong on this, and most of the paleontological community likewise rejected such statements. He was a fine artist and scientist, inseparably partnered in one person.

One of many examples of how Dolf Seilacher was both a scientist and an artist, in which through drawing he interpreted a series of movements made by a trilobite along an Early Cambrian seafloor, more than 500 million years ago. (Figure from Seilacher, A., 2007, Trace Fossil Analysis, Springer: p. 27. If you support the unification of science and art, then you must get this book.)

One of many examples of how Dolf Seilacher was both a scientist and an artist, in which through drawing he interpreted a series of movements made by a trilobite along an Early Cambrian seafloor, more than 500 million years ago. (Figure from Seilacher, A., 2007, Trace Fossil Analysis, Springer: p. 27. If you support the unification of science and art, then you must get this book.)

Like all students of paleontology who took their first toddling steps in the 1970s-80s, I first learned of Seilacher through his papers. In those readings, I also soon realized the most effective way to discern the key points of his papers was to skip straight to his exquisite illustrations. Following a long tradition of German artist-scientists, such as Albrecht Dürer, he could accurately reproduce what might have been evident from a photograph of a trace fossil, or the specimen itself. Yet the salient qualities of a trace fossil were somehow more deeply understood – and thus better communicated – through his drawing of that specimen. His illustrations often impelled a viewer to take a second, third, or fourth look at a trace fossil, prompting more learning and often provoking marvel at what he perceived.

In some instances, he “cheated” in his drawing by using a camera lucida. This is a clever device that, through a prism, projects the image of a subject onto paper, where its proportions and details can be traced and thus captured accurately by the person drawing it. However, in Dolf’s drawings, his tracings were often fortified and embellished with dramatic black-and-white contrast rendered by pen and ink. Even better, these so-called “illustrations” were used as launching points for interpretive drawings that presented provocative explanations for how a trace fossil was made. Sometimes he even added a whimsical touch to these figures, such as placing a little windmill next to the cross-section of a marine-invertebrate burrow. Was this science, or was this art? Yes.

When did I first meet Dr. Adolf Seilacher, a person many other paleontologists and I would later casually call “Dolf”? It was on a Geological Society of America field trip in Cincinnati, Ohio, in the fall of 1992. In retrospect, I was extremely lucky with that first meeting to watch him perform his expertise – and it was always a performance – in the field, rather than the sterile confines of a convention hall or conference room.

On this field trip, we paleontologists were looking at outcrops in the Cincinnati area, which bear some of the best Late Ordovician fossils (about 445 million years old) in the world. Among these fossils are brachiopods, bryozoans, snails, clams, crinoids, and other animals – such as trilobites – that have no living relatives today. You can walk up to most of these outcrops, close your eyes, and scoop up a handful of these fossils. I had also done my M.S. thesis in this area, so it was a trip back to familiar territory, and some of the fossils felt like old friends: I mean, really old friends.

Yet thanks to Dolf, these body fossils were not the stars of the field trip that day. When we went to an outcrop with numerous U-shaped burrows preserved in its limestones – trace fossils the field-trip leaders called Rhizocorallium – I witnessed his scientific process at work. After we had all listened to the field-trip leaders give their interpretation of the burrows, he sat down next to one of these trace fossils, and for about 10 minutes, he quietly drew in his field notebook. Gradually, some of us gathered around to see what had attracted his attention and we watched him draw. Once he had a critical mass for what he considered an adequate audience, he began sharing his thoughts, a didactic lecture accompanied by more drawing as he explained his conception of how the burrows were made by small animals living in a shallow sea hundreds of millions of years before that moment.

A field-trip memory expressed through drawing: my recollection of what Dolf Seilacher illustrated in his field notebook in October 1992 while explaining a 445-million-year-old burrow and how it was made. The burrow is the main U-shaped structure, and the lines in between are spreite, showing where the former location of the animal’s burrow. In my illustration here, the animal – either a small arthropod or worm – adjusted its burrow downward into the sediment, then to the right. The behaviors recorded here may have been from the animal feeding, reacting to changes in the surrounding sediment, or a combination of ecological cues.

“You see, this so-called ‘Rhizocorallium’ is just the beginning of a Zoophycos,” he said with his patented Teutonic confidence mixed with professorial charm. He then drew more in his field notebook to show what he meant, a slow-motion visualization that delivered his lesson unambiguously. In his estimation, the U-shaped burrow, which had curved lines showing where the animal had moved it, was only the start of a more complex feeding probe. In Dolf’s assessment, one trace fossil (what ichnologists would call Rhizocorallium) could have thus easily merged into another form, one we would then assign another name (Zoophycos). This was a clarifying moment for me as a young scientist and educator about the communicative power of drawing. As a result, I have tried to use drawing in my research articles, books, and teaching ever since.

Based on this sample of one, I did not know then that Dolf’s “hijacking” of field trips was a time-honored tradition for him. Moreover, I did not know then that nearly every paleontologist who had ever disagreed with him, or presented a hypothesis he somehow found lacking, was running the risk of being subjected to an intense and aggressive interrogation that over the years was nicknamed “Dolfing.”

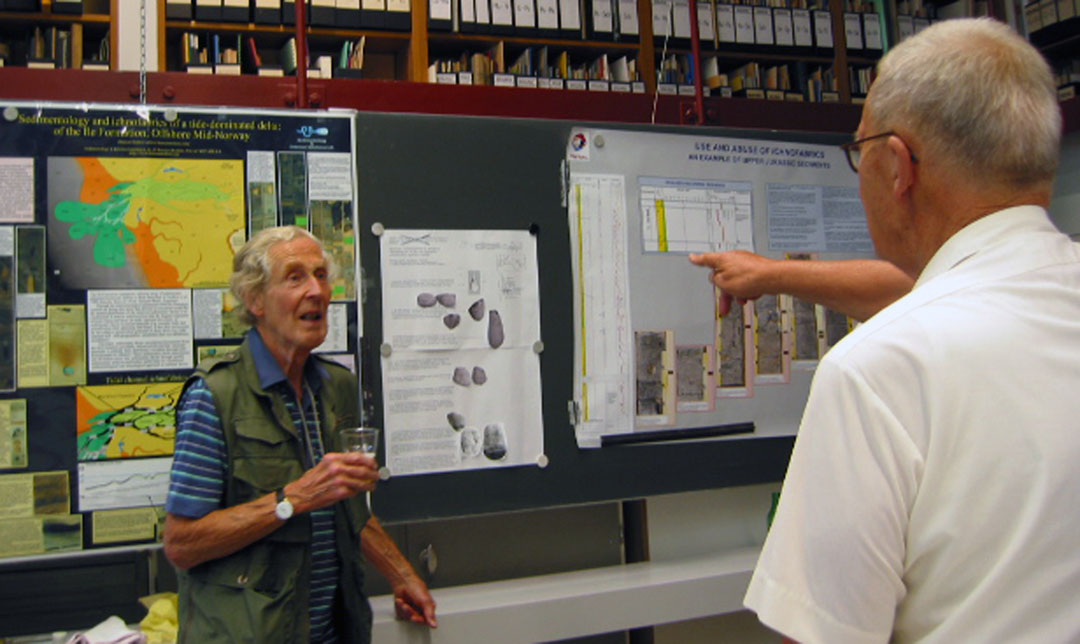

“Dolfing” in action, in which Dolf Seilacher would ask a series of penetrating questions as a follow-up to a helpful statement informing the “Dolfee” that she/he is completely wrong about everything ever. And just to show how no one was excused from potential “Dolfing,” regardless of their accomplishments and seniority, here he is subjecting Dr. Roland Goldring (1928-2005) to this treatment, just like he would have done to a well-meaning but woefully misguided graduate student. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Basel, Switzerland in July 2003.)

“Dolfing” in action, in which Dolf Seilacher would ask a series of penetrating questions as a follow-up to a helpful statement informing the “Dolfee” that she/he is completely wrong about everything ever. And just to show how no one was excused from potential “Dolfing,” regardless of their accomplishments and seniority, here he is subjecting Dr. Roland Goldring (1928-2005) to this treatment, just like he would have done to a well-meaning but woefully misguided graduate student. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Basel, Switzerland in July 2003.)

This harrowing critique was equal opportunity, in that he applied it to graduate students, senior professors, and everyone in between. For Dolf, getting the science right was far more important than honoring silly academic hierarchies. Although “Dolfing” occasionally caused discomfort in those getting “Dolfed,” these lopsided personal lectures often resulted in more details emerging, clearer explanations, and deeper understanding about a paleontological problem, meaning both the “Dolfer” and “Dolfee” learned more in the process. “Dolfing” became such a badge of honor, graduate students even wished for it to happen (“I’ve been Dolfed!”, they would say excitedly after surviving such an encounter.) One paleontologist friend of mine – after a colleague and I described “Dolfing” to her – said wistfully, “Oh…I want to be Dolfed!”

It was with much pleasure, then, that I got to watch “Dolfing” happen again during a field trip to the Cretaceous-Paleogene stratigraphic boundary in Recife, Brazil in 1994. This was when the “end-Cretaceous meteorite” hypothesis was still debated fiercely at professional meetings, with both proponents and skeptics fighting over the evidence. Preceding the field trip was a morning symposium on this contentious topic, much of which dealt with the 65-million-year-old boundary exposed at a nearby outcrop we would see later that afternoon.

In this session, one of the geologist speakers referred to a “massive” deposit of limestone as a tsunamite (a deposit formed by a meteorite-induced tsunami), which we were all supposed to see on the field trip. As soon as this speaker finished and the question-answer period began, Dolf sprang to his feet and declared, “You realize, of course, that if we find one burrow, it will completely negate your hypothesis.” Very simply, an animal would not have continued burrowing blithely on and in the ocean sediments while a gigantic sea wave washed over it. The speaker, taken aback by Dolf’s confident pronouncement, simply repeated that the deposit was “massive,” meaning it lacked any defined layering (bedding), and had no burrows. Ichnologists know better, though, as we sometimes translate “massive” as “There’s no bedding because it’s been completely burrowed, you ichnologically ignorant geologist!”

Dolf’s statement turned out to be a prophetic one. Later that afternoon, we field trip participants walked along the outcrop, looking at the layer of limestone interpreted as a meteorite-induced “tsunamite.” Sure enough, within ten minutes of inspecting, I found a burrow. Acting as a field-trip troll, I called out, “Oh Dolf, look what I found!” He came over and confirmed that yes indeed, it was a burrow, he quickly spotted dozens more, and the rest of the field trip was his for the taking. Many of the participants on the trip sat back and watched the fireworks, enjoyed the show, and we very nearly applauded at the end. Although I felt a little sorry for the field-trip leaders, it served as a good reminder that all you need is one burrow (or its factual equivalent) to upset a hypothetical apple cart.

Dolf Seilacher (left) delivering the intellectual equivalent of a bolide impact while standing in front of an outcrop containing evidence from the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in 1994 near Recife, Brazil.)

After such a memorable conference and field trip, when would Dolf and I cross trails again? Not until 1997, and through my initiative and in my backyard, here in Georgia. But that story is worth its own post, one I promise to tell next time.

(To Be Continued)

Reference (Which is Also Quite Likely the Best Book Ever Done on Trace Fossils That Also Includes Some Incredible Artwork):

Seilacher, A. 2007. Trace Fossil Analysis. Springer, Berlin: 226 p.