The first time Tom Rich and Patricia (Pat) Vickers-Rich visited Knowledge Creek was also their last. Their sojourn that day – December 18, 1980 – had been motivated by a renewed sense of exploration and scientific discovery on the coast of Victoria, Australia. But they also had no idea that a little footprint left by a dinosaur 105 million years before them there would soon become a part of their paleontological legacy.

Two of the first known dinosaur tracks, found in Victoria, Australia in the 1980s, but described for the first time this year. (Scale in centimeters; photo by Anthony Martin.)

Two of the first known dinosaur tracks, found in Victoria, Australia in the 1980s, but described for the first time this year. (Scale in centimeters; photo by Anthony Martin.)

Just two years before Tom and Pat’s trip to Knowledge Creek, a couple of students of theirs at the time, John Long and Tim Flannery, along with geologist Rob Glennie, discovered bits and pieces of dinosaur bones in rocks from the Early Cretaceous (120-105 million years ago) of coastal Victoria, Australia. Because these were the first dinosaur remains found in that region of Australia since 1903, the husband-wife paleontologist team decided they might prospect for more bones in other places with Early Cretaceous rocks. This was a daunting task, considering the lengthy and imposing coastal outcrops both west and east of the big city of Melbourne, Victoria, but they were up for the challenge.

A rare portrait of these two Australian paleontologists – Tom Rich and Pat Vickers-Rich – in which they are not a blur of discovering, publishing, and educating. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken in 2010.)

A rare portrait of these two Australian paleontologists – Tom Rich and Pat Vickers-Rich – in which they are not a blur of discovering, publishing, and educating. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken in 2010.)

Knowledge Creek was one of many spots on their map of coastal outcrops that had not been properly vetted for their fossils. It was named after a modest drainage that cut across the Cretaceous rocks in the Otway Ranges and located about 2.5 hours drive west of where Tom and Pat lived in Melbourne. So off they went to assess it, a decision they soon regretted.

Need to find the way to the outcrop at Knowledge Creek? Just take a wallaby trail partway down, look for the somewhat-human trail, take a right, then a left, and keep going downhill until you find the creek with the leeches. How do you get back up? No bloody idea, mate. (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

Need to find the way to the outcrop at Knowledge Creek? Just take a wallaby trail partway down, look for the somewhat-human trail, take a right, then a left, and keep going downhill until you find the creek with the leeches. How do you get back up? No bloody idea, mate. (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

The terrain is what prompted them to soon question their sanity. To access the outcrops then (and still) required driving along an unmarked dirt road high above the cliffs, finding a wallaby trail or other such clearing through the coastal scrub forest, bushwhacking your way down a steep, muddy slope, crossing leech-infested Knowledge Creek, and then – once on the rocky marine platform, eyes down looking for fossils – not slipping on the algae-covered rocks and getting pummeled by waves. While there, they also tried not to think about the trip back up. One challenge at a time.

Here they found Victoria’s first known dinosaur track, and the first discovered in all of southern Australia. The track was exposed on the marine platform about 200 meters (660 feet) east of where Knowledge Creek flowed out and onto the rocks. It stood out clearly as a single, raised, dark-brown three-toed entity on a flat sandstone surface, with no matching companion tracks nearby.

Discovery site of the first known dinosaur track in Victoria, Australia, found by Tom Rich and Pat Vickers-Rich on December 18, 1980. The spot where they saw the track on the marine platform would have been about 100 meters to the left, where the big wave in this photo is about to smash. (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

Discovery site of the first known dinosaur track in Victoria, Australia, found by Tom Rich and Pat Vickers-Rich on December 18, 1980. The spot where they saw the track on the marine platform would have been about 100 meters to the left, where the big wave in this photo is about to smash. (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

Luckily, Tom and Pat had brought hammers and chisels with them. so where a dinosaur foot once pressed into soft sand, they added their own traces to its hardened periphery. Into a backpack the little slab went and they carried it out, their feet leaving longer and deeper prints than before as they slogged back up the slope.

The first known dinosaur track from Victoria, Australia. It’s only about 10 cm (4 in) wide and long, and it’s all by its lonesome self, but it’s a pretty track. Also, check out those chisel traces around it, made by Tom and/or Pat Vickers-Rich. (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

The first known dinosaur track from Victoria, Australia. It’s only about 10 cm (4 in) wide and long, and it’s all by its lonesome self, but it’s a pretty track. Also, check out those chisel traces around it, made by Tom and/or Pat Vickers-Rich. (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

They took the track to Museum Victoria, where it was assigned a specimen number and label, then put in a drawer in the paleontological collections in the basement of the old Exhibition Hall for the museum. As Victoria’s only known dinosaur track – and such a neatly defined one – it became iconic through the rest of the 1980s and afterwards. Because its shape so clearly said “dinosaur track!”, it was frequently displayed in the museum, and photos of it showed up in books and articles on the paleontology of the area. As a sign of Pat’s passion for science education and outreach, she had reproductions made of it and gave these away to local schools so Australian students could learn about Victoria’s only dinosaur track by proxy.

The old Exhibition Hall of Museum Victoria in downtown Melbourne, Australia, which houses the extensive fossil collections for the museum, including its dinosaur tracks. (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

The old Exhibition Hall of Museum Victoria in downtown Melbourne, Australia, which houses the extensive fossil collections for the museum, including its dinosaur tracks. (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

Oddly, more than thirty years passed, and this dinosaur footprint was neither described nor diagnosed. Despite its importance, it was overshadowed by far more abundant and seemingly more exciting dinosaur bones in outcrops near Knowledge Creek. This place and its fossils were discovered by Tim Flannery, Michael Archer, and Tom Rich on December 13, 1980, and only five days before Tom and Pat descended into Knowledge Creek. Tom called it Dinosaur Cove, and thanks to its fossils and total coolness as a place name, it stuck. Here’s what he said about its origin story:

That night, needing a name for this then unnamed cove, I scribbled in my notes ‘Dinosaur Cove,’ not thinking then that it would ever have any particular significance.

Dinosaur Cove, one of the most important fossil sites in Australia and for polar dinosaurs in the Southern Hemisphere. (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

Dinosaur Cove, one of the most important fossil sites in Australia and for polar dinosaurs in the Southern Hemisphere. (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

Tom Rich next to the sealed tunnel at Dinosaur Cove, where he, Pat Vickers-Rich, and many volunteers extracted many fossils during the 1980s and early 1990s. (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

Tom Rich next to the sealed tunnel at Dinosaur Cove, where he, Pat Vickers-Rich, and many volunteers extracted many fossils during the 1980s and early 1990s. (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

Here was where this part of Australia became justifiably famous for its dinosaur fossils in the 1980s and 1990s, as Tom and Pat, along with dedicated field crews, extracted hundreds of skeletal bits and pieces of dinosaurs and many other animals that lived there. What made these remains even more important, though, was how their former owners lived near the Cretaceous South Pole, when Australia was still connected to Antarctica. This meant Tom, Pat, and their colleagues were documenting what was then one of the few known polar-dinosaur assemblages in the world. For about ten years, they and their teams also performed some of the hardest labor any dinosaur-recovery effort should ever have to endure, described in their book Dinosaurs of Darkness (2000).

The cover of Dinosaurs of Darkness (2000), coauthored by Tom Rich and Pat Vickers-Rich, with cover art by famed paleoartist Peter Trusler.

The cover of Dinosaurs of Darkness (2000), coauthored by Tom Rich and Pat Vickers-Rich, with cover art by famed paleoartist Peter Trusler.

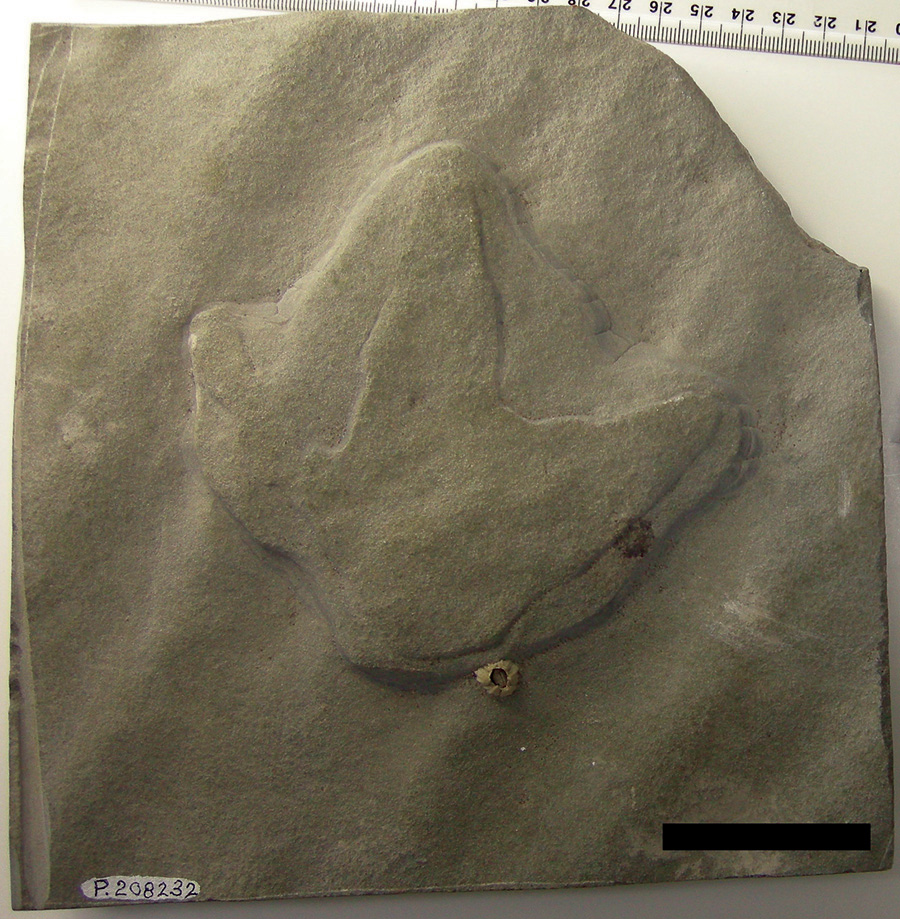

Nearly nine years went by after the discovery of the track at Knowledge Creek, as it remained the only one in Victoria. That changed in early 1989, when geologist Helmut Tracksdorf found two more. While out for a walk along the genteel seashore near the small coastal community of Skenes Creek (Victoria), he spotted the tracks on a marine platform only 50 meters (~160 feet) south of The Great Ocean Road. Although these footprints were about 35 kilometers (18+ miles) east of Knowledge Creek, they were also in Early Cretaceous rocks, from a little more than 100 million years old. One of the tracks had three clearly defined toes, whereas the other was not so obviously a track. (Spoiler alert: But it was.)

Helmut next did the right thing, and reported the tracks and their location to Tom Rich at Museum Victoria. On March 18, 1989, a field crew from the museum stopped by the marine platform, found the tracks, used a portable rock saw to cut each out into manageable sizes, and loaded the two slabs into a vehicle for the drive back to Melbourne. Again, these two tracks received a Museum Victoria specimen number and were placed in a drawer, sharing the same Exhibition Hall basement with the Knowledge Creek track. And there they stayed, also unstudied until just recently.

The better-defined of the two Skenes Creek dinosaur tracks discovered by Helmut Tracksdorf in 1989. The scale bar is 5 cm (2.5 in), so this track is also about 10 cm (4 in) wide, has three toes, and raised, just like the Knowledge Creek track. You can also tell it was on a marine platform because of the little crustacean (barnacle) on its lower right edge. (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

The better-defined of the two Skenes Creek dinosaur tracks discovered by Helmut Tracksdorf in 1989. The scale bar is 5 cm (2.5 in), so this track is also about 10 cm (4 in) wide, has three toes, and raised, just like the Knowledge Creek track. You can also tell it was on a marine platform because of the little crustacean (barnacle) on its lower right edge. (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

The not-so-well-defined of the two Skenes Creek dinosaur tracks discovered by Helmut Tracksdorf in 1989. Yeah, I know, it’s blobby and you have to squint and maybe have a few beers before it starts looking like a three-toed dinosaur track, but it’s a track. Just like bones, tracks aren’t always perfectly preserved, either. (Scale in centimeters; photo by Anthony Martin.)

The not-so-well-defined of the two Skenes Creek dinosaur tracks discovered by Helmut Tracksdorf in 1989. Yeah, I know, it’s blobby and you have to squint and maybe have a few beers before it starts looking like a three-toed dinosaur track, but it’s a track. Just like bones, tracks aren’t always perfectly preserved, either. (Scale in centimeters; photo by Anthony Martin.)

Oddly, Helmut did not receive any confirmation that the tracks had been collected. He only learned of their acquisition indirectly later in 1989 when he saw rectangular holes in the marine platform marking where the tracks used to reside. Also, whoever wrote the specimen label in 1989 did not record that he was the person who discovered the tracks. Years later, I asked Tom, Pat, and others at the museum then, and no one could recall who found it. Only in October 2013 did I and everyone else finally find out it was Helmut, who wrote to me to confess his role after reading a blog post of mine. For that, I thank him most sincerely for his long-time non-credited contribution to the dinosaur ichnology of Victoria.

Helmut Tracksdorf, who in 1989 discovered Victoria’s second and third dinosaur tracks, as well as Victoria’s first dinosaur trackway. Here he is more recently taking a rest from bushwalking by sitting on Cretaceous rocks of the Victoria coast. Also, he either lost his boots or was busy making his own distinctive tracks for future generations to discover. (Photo courtesy of Helmut Tracksdorf.)

In February 2006, about 17 years after Helmut’s find, I was in Australia on a rare sabbatical from my university (very rare, too rare, as in, the only one ever). I was there primarily to work on a science-education project with Pat, who I had long admired as both a scientist and science educator. Yet within my first week there, Tom Rich invited me to go with him to the Dinosaur Dreaming dig site near Inverloch, Victoria. Tom, Pat, and the other dinosaur hunters of Museum Victoria and Monash University had abandoned Dinosaur Cove since the early 1990s, and Dinosaur Dreaming was their “new” polar-dinosaur dig site. Again, it was relatively close to Melbourne (only a little more than a two-hours drive away), and although it had its own set of logistical challenges, it was was much easier to access than Dinosaur Cove.

On the morning of February 26, 2006, Tom drove just him and me from Melbourne to the Dinosaur Dreaming site, and I was soon walking on the Cretaceous rocks of Victoria for the first time. That same day, I found two large theropod dinosaur tracks, the first ever found in Victoria, but which Tom instantly rejected as real when I showed them to him. Later that day, he drove off with my field boots on the top of his Land Rover. But both of those are stories that can be told another time.

My first view of the Dinosaur Dreaming site (near Inverloch, Victoria) on February 24, 2006. The photo was taken from a car park just above, with wooden steps leading below, lending to a bit more civilized journey for volunteers compared to Knowledge Creek or Dinosaur Cove. (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

My first view of the Dinosaur Dreaming site (near Inverloch, Victoria) on February 24, 2006. The photo was taken from a car park just above, with wooden steps leading below, lending to a bit more civilized journey for volunteers compared to Knowledge Creek or Dinosaur Cove. (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

Since that day in 2006, I’ve worked with Pat, Tom, and others there on-and-off for the past ten years, during which I have found and/or documented a few other trace fossils in that part of the world. Some of these turned out to be paleontologically significant (such as this one, this one, this one, and oh yeah, this one), and more are on the way. It’s been a really good journey for all of us, and my working with Pat and Tom changed my life and career for the better. I am extremely and unreservedly grateful to them for their mentorship and friendship.

Yet probably the most important gesture of support for my ichnological work in Victoria came from Tom in 2010. He decided to apply unused Museum Victoria research funds to fly me round-trip from Atlanta, Georgia to Melbourne, Victoria, and paid for a month of our doing field work together along the Victoria coast. It was an unforgettable experience in many ways, which I partially documented in my first blog (The Great Cretaceous Walk, dormant since 2011). We walked together for probably a few hundred kilometers on the rugged Victoria coast, him looking for bones, and me looking for dinosaur tracks, insect and crustacean burrows, and other trace fossils. You could say it was a bit of an adventure.

Yours Truly in May 2010 with Cretaceous sandstones to the left and the ocean to the right, near the start of what I called “The Great Cretaceous Walk.” (Photograph by Tom Rich.)

Yours Truly in May 2010 with Cretaceous sandstones to the left and the ocean to the right, near the start of what I called “The Great Cretaceous Walk.” (Photograph by Tom Rich.)

Three weeks into that excursion along the Victoria coast with Tom, I’m happy to say I finally helped end the drought of dinosaur-track discoveries in Victoria, which had seemingly been in limbo since the 1980s. While walking along Milanesia Beach, west of Knowledge Creek and Dinosaur Cove, I spotted a motherlode of small dinosaur tracks on a rock slab there. Tom and Greg Denney – a long-time friend of Tom’s from Dinosaur Cove – were with me at the time, and Greg soon found another slab with more dinosaur tracks next to mine. The detailed story of this day and the discovery of these tracks is in a chapter titled The Great Cretaceous Walk in my book Dinosaurs Without Bones (2014).

Although the two slabs together only held twenty tracks, it still constitutes the best assemblage of polar-dinosaur tracks in the Southern Hemisphere. Would someone have eventually found these or other dinosaur tracks at Milanesia Beach? Probably. But thanks to Tom’s support and Greg’s help, we found them a lot sooner.

Most of the video footage shown here, along with thousands of photographs (and many more footsteps) were taken at Milanesia Beach by my wife Ruth Schowalter. We shared many adventures on the Victoria coast and elsewhere in Australia.

Thus in 2013, when paleontologist Erich Fitzgerald of Museum Victoria sent out a request for former and current colleagues of Tom Rich to contribute research papers for a special volume in his honor, I readily accepted. But what topic could I address that would be scientifically meaningful, while also linking it to Tom and Pat? That’s when I decided to dust off my detailed notes, measurements, and photos taken of Victoria’s first dinosaur tracks during previous visits to the museum. There were just three footprints to study: the one Tom and Pat found in 1980, and the two Helmut found in 1989.

The two best-preserved of the Victoria dinosaur tracks of the 1980s. The one on the left is from the marine platform near Skene’s Creek and the one on the right is from Knowledge Creek. Even though they look almost identical, they were separated by more than 30 km (18 miles). (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

The two best-preserved of the Victoria dinosaur tracks of the 1980s. The one on the left is from the marine platform near Skene’s Creek and the one on the right is from Knowledge Creek. Even though they look almost identical, they were separated by more than 30 km (18 miles). (Photo by Anthony Martin.)

With only three tracks to examine, this was a manageable study, and I did it in an old-fashioned way, using a ruler, calipers, pencils, notebook, my eyes, and occasionally my brain as the main instruments for scrutinizing the tracks. No lasers, CT scanners, 3-D printing, virtual reality, aerial drones, avatars, self-aware AI devices, or other forms of technology were necessary for doing this science. All I needed was for one of the collections managers – David Pickering – to retrieve the tracks from Museum Victoria collections for me, a table to support them, and I was in business.

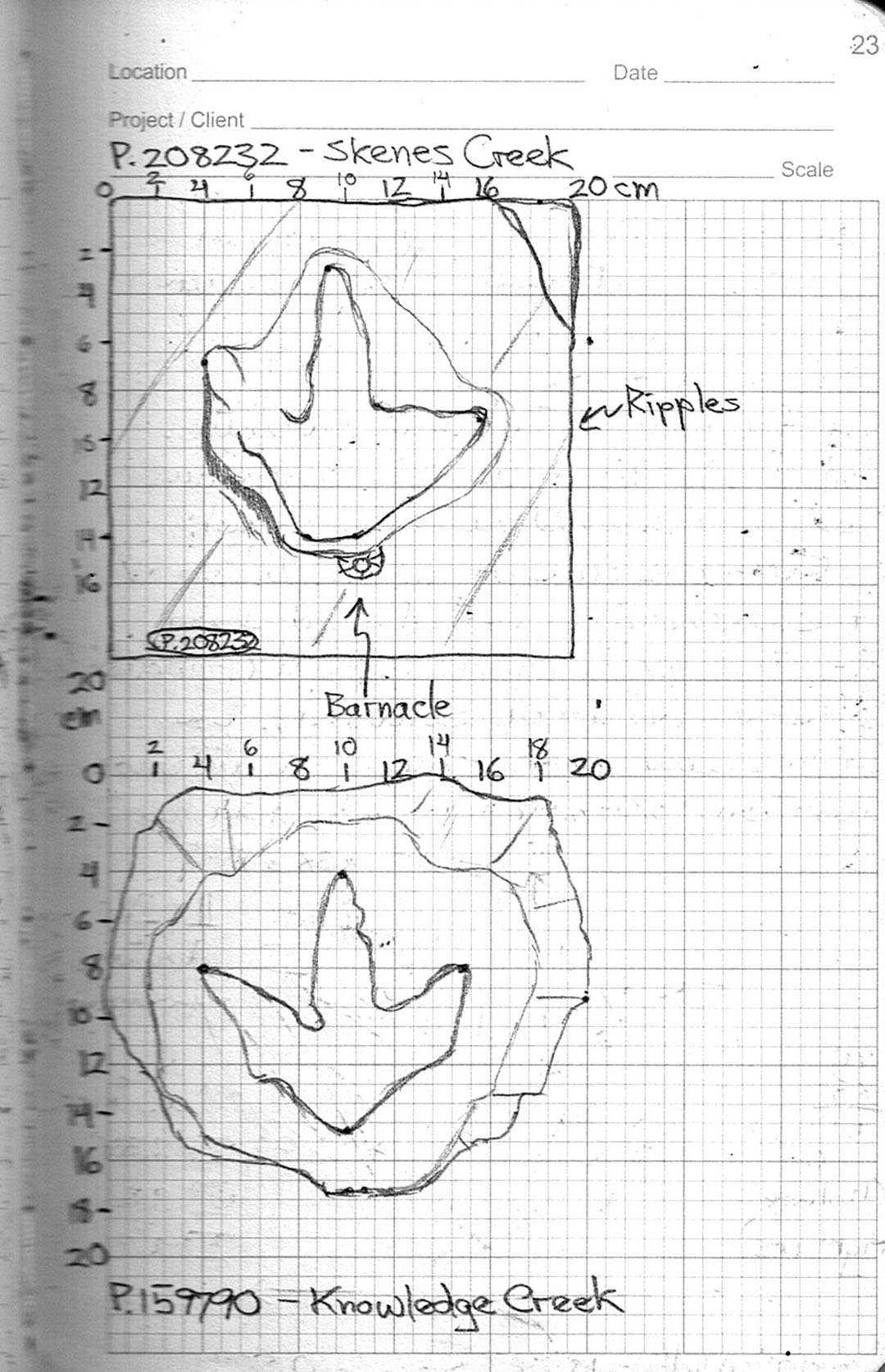

Because drawing is one of the best ways for me to observe, I started with making scaled sketches of the tracks, which helped me to pick up details missed in times before when just glancing at the tracks. This is an example of practicing what I preach, as I often require my students to make labeled drawings as part of their scientific process.

Scaled drawings (“maps”) of the two tracks, drawn on May 25, 2010, which helped me to compare their relative dimensions and forms. These and other sketches, descriptions, and measurements are in a field notebook, which I prefer using even when in a museum.

Scaled drawings (“maps”) of the two tracks, drawn on May 25, 2010, which helped me to compare their relative dimensions and forms. These and other sketches, descriptions, and measurements are in a field notebook, which I prefer using even when in a museum.

I also measured the tracks so that they were thoroughly quantified. Ideally, this meant I would have recorded track width, track length, widths and lengths of individual toes, and angles between the toes. However, two of the three tracks (from Skenes Creek) were not preserved well enough to measure everything I wanted, although one of those was good enough I could compare its measurements to those of the Knowledge Creek track. These numbers, when combined with my qualitative descriptions, later helped me to identify “who” (which dinosaurs) made the tracks.

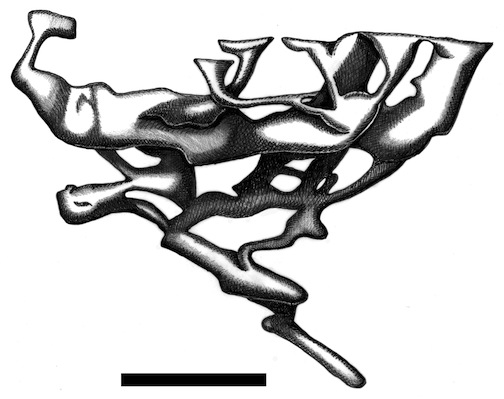

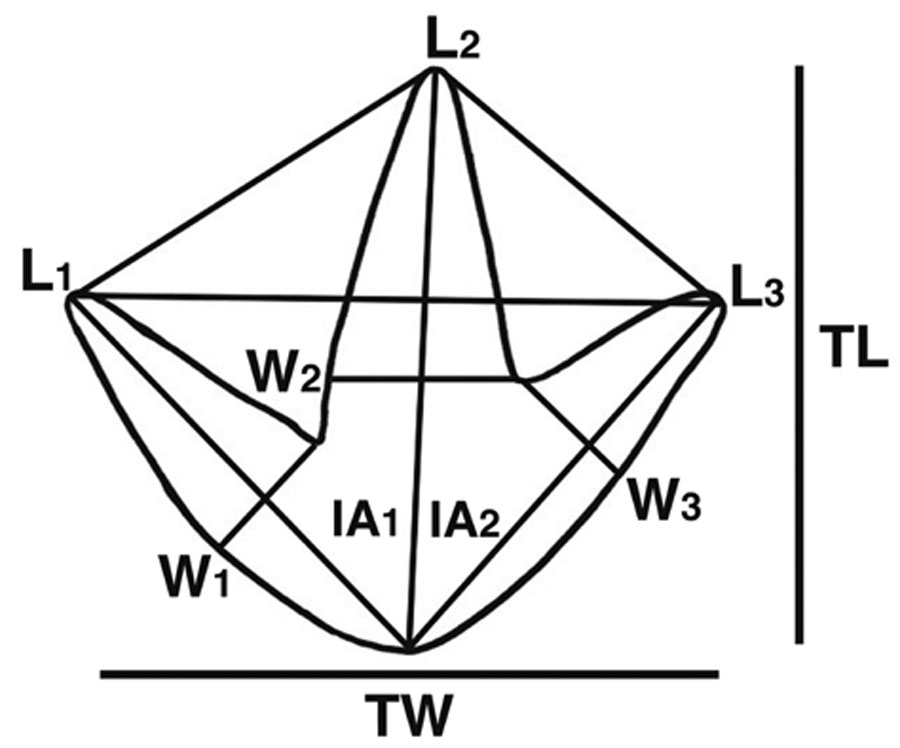

Diagram showing what was measured in the Victoria dinosaur tracks: TW = total width, TL = total length, L1-3 = digit lengths, W1-3 = digit widths, and IA1-2 = interdigital angles. Figure from Martin (2016).

Diagram showing what was measured in the Victoria dinosaur tracks: TW = total width, TL = total length, L1-3 = digit lengths, W1-3 = digit widths, and IA1-2 = interdigital angles. Figure from Martin (2016).

Based on my perusal, these three-toed tracks were made by small ornithopod dinosaurs, often informally called “hypsilophodontids.” Although such dinosaurs do not belong an evolutionarily united group (clade), dinosaur paleontologists still use this term informally when talking about small ornithopods that lived during the Late Jurassic through the Cretaceous Period in different parts of the world. Among the Victorian dinosaurs found and documented by Tom, Pat, and others, hypsilophontids are the most common dinosaurs, abundantly represented by bones and teeth.

What’s significant about my interpretation is that these are the first known small ornithopod tracks from Victoria, and by default, all of southern Australia. (All other dinosaur tracks found in Victoria since the 1980s are from theropods, both bird and non-bird.) This is important because it officially connects the body-fossil record of small ornithopods with their probable trace fossils for the first time. Another meaningful facet of this connection is how the tracks scientifically affirm details of Peter Trusler’s remarkable 1992 painting, Early Cretaceous in Southeastern Australia – Spring Scene. In this artwork, he used the Knowledge Creek track as a template for depicting tracks made by small hysilophodontids on a sandy riverbank following spring thaws (and flooding) of that formerly polar region. So I was most pleased to have my science finally connect with his predictive (and gorgeous) artwork.

Peter Trusler’s extraordinary painting Early Cretaceous in Southeastern Australia – Spring Scene (1992), visualizing then-fresh three-toed tracks left by hysilophontid dinosaurs on a sandy riverbank after spring-thaw floodwaters had waned. Let me emphasize that this is a painting and he made it in 1992, meaning there is nothing digital about it. When I show it projected on a screen in my talks, people gasp because they at first think it is a photograph, but also because of its beautiful, evocative composition. No wonder I wanted it to be on the cover of my book Dinosaurs Without Bones.

Peter Trusler’s extraordinary painting Early Cretaceous in Southeastern Australia – Spring Scene (1992), visualizing then-fresh three-toed tracks left by hysilophontid dinosaurs on a sandy riverbank after spring-thaw floodwaters had waned. Let me emphasize that this is a painting and he made it in 1992, meaning there is nothing digital about it. When I show it projected on a screen in my talks, people gasp because they at first think it is a photograph, but also because of its beautiful, evocative composition. No wonder I wanted it to be on the cover of my book Dinosaurs Without Bones.

One remarkable point about the two well-preserved tracks from Knowledge Creek and Skenes Creek, though, is their strikingly similar size and form. Despite being separated by more than 30 kilometers (18 miles) they could have been made by not just the same species of dinosaur, but the same dinosaur. They were even preserved the same, protruding from the top of the bed, instead of as depressions or natural casts on the bottom of a bed. This odd preservation likely was caused by the tracks filling with a different sediment holding the track, which then cemented more firmly, leaving the track behind when modern-day ocean waves eroded the top surface.

Yet another insight that came out of the study, and a totally unexpected one, resulted from correspondences with Helmut and ace Victoria-fossil-finder Mike Cleeland. After exchanging a few messages with one another, Mike decided that he and his wife Pip would try to re-locate the original discovery site for the tracks by looking for the 1989 saw marks in the rocky marine platform. And re-locate them they did. Even better, the rock-saw traces lined up, indicating that the two tracks were aligned, and likely from a trackway made by the same individual dinosaur. This means Helmut found Victoria’s first dinosaur trackway – consisting of two or more tracks made by the same dinosaur – in 1989. This was 21 years before I found what I thought was the “first” dinosaur trackway at Milanesia Beach, so I need to stop bragging about that. In my face!

The site of the first known dinosaur trackway discovered in Victoria (Australia), originally found in 1989 and marked today by rock-saw marks. (Pip Cleeland for scale; photo by Mike Cleeland.)

The site of the first known dinosaur trackway discovered in Victoria (Australia), originally found in 1989 and marked today by rock-saw marks. (Pip Cleeland for scale; photo by Mike Cleeland.)

The sequential steps of a small ornithopod dinosaur represented by rock-saw cuts. (Photo by Mike Cleeland.)

The sequential steps of a small ornithopod dinosaur represented by rock-saw cuts. (Photo by Mike Cleeland.)

Given such intriguing results, it was time to write the article and have it reviewed. However, it took a while. I wrote the main text of the article in a few months, then picked out and labeled photos of the tracks, made a few illustrations, put them all together into one coherent manuscript, and submitted the article for peer review in June 2014. A few months later I received the reviews, which were mostly positive and helpful. (Thanks, reviewers!) I changed the article accordingly, then resubmitted it a few months later. However, I didn’t see page proofs of the corrected article until July of 2015, and the final galley proofs until just a few months ago. So you could say I was most pleased when it was published last month, although probably not as much as the editor of the volume.

Because the article was one of many in a special volume honoring Tom, all authors were told to keep quiet about it so that it would be a big surprise for Tom and Pat once published. Somehow we did it, and on July 19, 2016, Tom received his bound copy of the volume and at Museum Victoria, flanked by former students Tim Flannery and Erich Fitzgerald. It must have been quite a special moment, and I smiled when I saw the following photo posted on Twitter the next day.

The Tom Rich special volume was complete once the secret was unveiled, which happened on July 19, 2016 at Museum Victoria. Here Tom is accompanied by his former students Tim Flannery (left) and Erich Fitzgerald, the latter of whom did a ripper of a job on editing the volume. (Photo by Alastair Evans.)

The Tom Rich special volume was complete once the secret was unveiled, which happened on July 19, 2016 at Museum Victoria. Here Tom is accompanied by his former students Tim Flannery (left) and Erich Fitzgerald, the latter of whom did a ripper of a job on editing the volume. (Photo by Alastair Evans.)

Other than everything else I said before, are there two takeaway messages from this study? Yes. One is that amateur contributions have been and always will be important for paleontology. Helmut Trackdorf’s discovery of the first dinosaur trackway in Victoria in 1989 and his contacting me about it in 2013 may seem small when compared to other discoveries in that area of the world. Yet it is a puzzle piece that now fits better in our picture of Cretaceous life in that area of the world: every little bit helps. Also, now that we’ve relocated the original discovery spot, we might find more dinosaur tracks near there. We’ll see.

The second message is that well-curated museum collections are damned important for doing a lot of good science in paleontology. For instance, I have been to Knowledge Creek three times, and on all three of those visits I looked for the chiseled hole in the marine platform where Tom Rich and Pat Vickers-Rich found that first dinosaur track in 1980. Alas, I did not find it. So if they had not collected the track and put it in Museum Victoria, it may never have been found and studied by me or anyone else. The same goes for the Skenes Creek tracks found my Helmut Tracksdorf in 1989: If these hadn’t gone to the museum, no study of those, either.

Those tracks belonged in a museum, and so did I. But if the museum wasn’t there to act as a repository for the specimens, or it didn’t have collections to study, then I wouldn’t have been there either. What’s the moral of the story? Support museums.

In summary, this is a little article about a few fossil tracks made by two small dinosaurs a long time ago in a cold place very far away from when and where I am right now in Atlanta, Georgia. Yet I am very proud of it as a way for me to give something back to my mentors and other discovers out there, as well as all of the good people in Victoria who helped make it happen. Good on ya, mates!

*****************************************************************************

The citation for the original research article is:

Martin, A.J. 2016 A close look at Victoria’s first dinosaur tracks. Memoirs of Museum Victoria, 74: 63-71.

The article is also open access and free to download at the following link:

A Close Look at Victoria’s First Dinosaur Tracks

Blog Posts Reporting on the Article:

Dinosaur Tracks Lead Paleontologist through Museum to Mentor’s Discovery: Carol Clark, eScienceCommons (Emory University), July 29, 2016.

Tracking Australia’s Dinosaur Past: Jon Tennant, PLoS One Paleo Community, August 8, 2016.

*****************************************************************************

Afterthought: The main reason why I published this article with Memoirs of Museum Victoria rather than another journal was to honor Tom Rich. But what sealed the deal for me was learning that the article would also be freely available to the people of Victoria – or anyone else, for that matter – with an Internet connection. Some things in life are more important than journal impact factors. So there.