(This post is the third in a series of three about my field work on the trace fossils of the Late Cretaceous (75 million-year-old) Two Medicine Formation, which I just completed a week ago. My previous two posts, which mostly explain the scientific importance of this field work, are Tracing the Two Medicine and Burrowing Wasps and Baby Dinosaurs.)

Looking back on three weeks of field work in the Late Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation, one of the realizations I had was how long it took before I could see more of what was there. The most frustrating part of this realization, though, is also knowing that I still missed plenty. This mix of satisfaction and unease is the duality that often accompanies the birthing and honing of search images, a visual training that enables paleontologists to find the fossils we want to find whenever we walk around a field site and look.

This outcrop of the Late Cretaceous (75 mya) Two Medicine Formation in central Montana is chock-full of fossils, but you might not know that from just looking at this picture. That means you have to get out onto the rocks and look closely for them, but first make sure you have the right search images for finding them. (Photograph by Ruth Schowalter.)

This outcrop of the Late Cretaceous (75 mya) Two Medicine Formation in central Montana is chock-full of fossils, but you might not know that from just looking at this picture. That means you have to get out onto the rocks and look closely for them, but first make sure you have the right search images for finding them. (Photograph by Ruth Schowalter.)

The Two Medicine Formation in particular presents a major challenge for cultivating search images because of the variety of fossils in it. Moreover, most of these fossils require very different search images. For example, over my three weeks of prospecting, I looked for the following fossils:

- Plant root traces

- Invertebrate burrows and tracks

- Insect cocoons and pupal chambers

- Dinosaur tracks

- Dinosaur nests

- Dinosaur eggshells

- Dinosaur coprolites

- Dinosaur bones

- Dinosaur toothmarks (on dinosaur bones)

I also found a few other fossils I didn’t expect to find, but there they were. This happenstance served as a good reminder that simply going out into the field with a bullet-point checklist of what you think you’ll find (like what you just read) isn’t good enough. In other words, you also need to see what’s there, rather than just what you expect to be there.

On top of looking for these fossils, I’m a geologist, too. This means I also paid close attention to the rock types in the Two Medicine Formation – sandstones, mudstones, conglomerates, limestones – and their physical sedimentary structures – such as cross-bedding or graded bedding. Moreover, Two Medicine strata in the field area are not necessarily in their original horizontal positions, but instead are bent, tilted, and faulted in places. This is where training I had in structural geology – the study of how rocks were deformed – came in handy.

Originally horizontal sedimentary strata were bent upward into a fold, which we geologists normally call an anticline. In such folds, the fossils in the center of the fold are geologically older, whereas the fossils on the outside of the fold are younger. That is, unless the strata were overturned, in which case we’d call it antiformal syncline, then the fossils would have the opposite age relations. Thank you for teaching this, structural geology professors! (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Originally horizontal sedimentary strata were bent upward into a fold, which we geologists normally call an anticline. In such folds, the fossils in the center of the fold are geologically older, whereas the fossils on the outside of the fold are younger. That is, unless the strata were overturned, in which case we’d call it antiformal syncline, then the fossils would have the opposite age relations. Thank you for teaching this, structural geology professors! (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

It’s not my fault, so we’ll blame the Two Medicine Formation for this breakage of sedimentary rocks. Based on how it looks like the fault block on the right moved up relative to the one on the left, I think this is a reverse fault, which – like the anticline and almost everything else on earth – was caused by plate tectonics. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

It’s not my fault, so we’ll blame the Two Medicine Formation for this breakage of sedimentary rocks. Based on how it looks like the fault block on the right moved up relative to the one on the left, I think this is a reverse fault, which – like the anticline and almost everything else on earth – was caused by plate tectonics. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Thus whenever I stepped into the field each day, I had to rapidly switch, combine, or otherwise tap into different types of vision. I’ve often jokingly referred to my ability to spot traces and trace fossils in the field as “ichnovision” (my most likely comic-book hero superpower), and my geological training means I’m using “geovision.” Yet in the Two Medicine Formation – a rock unit world-famous for its dinosaur bones and eggs – I also had to use “osteovision” (seeing fossil bones) and “oovision” (seeing fossil eggshells). These forms of fossil vision are tough for me, as I never see dinosaur bones or eggshells in the southeastern U.S., which is where I spend most of my time in the field.

So just to give you an appreciation of what it was like during my three weeks of looking for fossils in the Two Medicine Formation, here are a few photos and brief descriptions of some fossils I found. To be sure, there was much more than this, but at least I can share these for now so you can begin to see through my eyes.

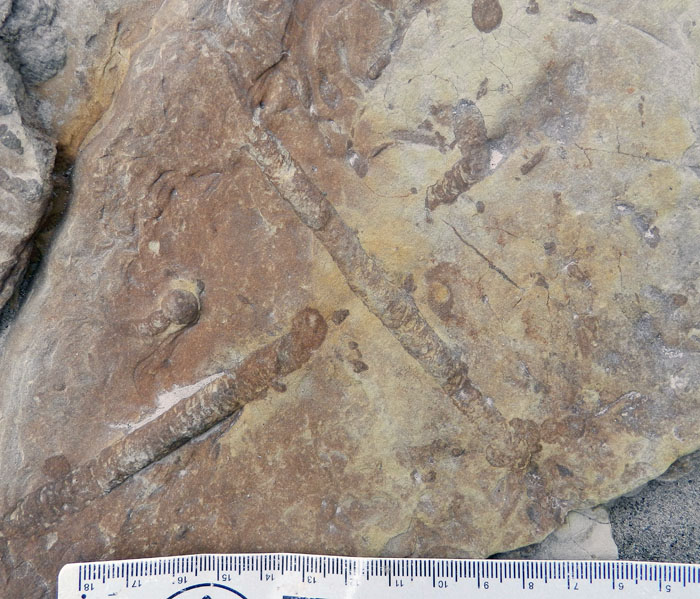

These odd-looking structures weathering out of an outcrop in the Two Medicine Formation had variable diameters, central cores filled with calcite, and branched in places. I’m fairly sure these are fossil plant root traces, but they were the only ones I saw like them during three weeks of field work. So I remain a little skeptical of my identification, and remain open to their being some geological features I’ve just never seen before then. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

These odd-looking structures weathering out of an outcrop in the Two Medicine Formation had variable diameters, central cores filled with calcite, and branched in places. I’m fairly sure these are fossil plant root traces, but they were the only ones I saw like them during three weeks of field work. So I remain a little skeptical of my identification, and remain open to their being some geological features I’ve just never seen before then. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

These are longitudinal sections of horizontal burrows in a sandstone, showing off their beautifully expressed internal structures called meniscae. Meniscae are formed by burrowing invertebrates – such as beetle larvae or cicada nymphs – that pack their burrow with sediment behind them as they move. This means the convex side of the meniscae points in the direction the animal was moving. Go ahead, apply that principal and see what you figure out for yourself. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

These are longitudinal sections of horizontal burrows in a sandstone, showing off their beautifully expressed internal structures called meniscae. Meniscae are formed by burrowing invertebrates – such as beetle larvae or cicada nymphs – that pack their burrow with sediment behind them as they move. This means the convex side of the meniscae points in the direction the animal was moving. Go ahead, apply that principal and see what you figure out for yourself. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

These are more invertebrate burrows, but they’re vertically oriented, meaning you only see their circular cross-sections when you look at the top bedding-plane surface of this sandstone. Notice how some of them are open but others are filled with sandstone. The open ones were filled with mud originally, but that softer sediment has since weathered out, leaving them hollow. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

These are more invertebrate burrows, but they’re vertically oriented, meaning you only see their circular cross-sections when you look at the top bedding-plane surface of this sandstone. Notice how some of them are open but others are filled with sandstone. The open ones were filled with mud originally, but that softer sediment has since weathered out, leaving them hollow. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

These are invertebrate tracks, and they form a distinctive enough pattern that I recognized them as a trackway, where the trackmaker (probably a freshwater horseshoe crab) turned. But they’re also preserved in positive relief (“sticking out”) because the original traces were filled with sand, which made a natural cast of the tracks. Think about how you have to reverse your concept of tracks to recognize these. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

These are invertebrate tracks, and they form a distinctive enough pattern that I recognized them as a trackway, where the trackmaker (probably a freshwater horseshoe crab) turned. But they’re also preserved in positive relief (“sticking out”) because the original traces were filled with sand, which made a natural cast of the tracks. Think about how you have to reverse your concept of tracks to recognize these. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

One of my main research interests in the Two Medicine Formation is its insect trace fossils, which include some of the best-preserved fossil insect cocoons I’ve ever seen in the geologic record. See where the patterns of their original weaves? These cocoons were likely made by wasps – or something acting very much like wasps – 75 million years ago. I usually prospected for these cocoons by looking for their distinctive oval shapes on the ground, then looked more closely for the weave pattern. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

One of my main research interests in the Two Medicine Formation is its insect trace fossils, which include some of the best-preserved fossil insect cocoons I’ve ever seen in the geologic record. See where the patterns of their original weaves? These cocoons were likely made by wasps – or something acting very much like wasps – 75 million years ago. I usually prospected for these cocoons by looking for their distinctive oval shapes on the ground, then looked more closely for the weave pattern. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

This is what a fossil insect cocoon looks like in an outcrop. Sometimes a burrow would be connected to the cocoon, showing where the original mother insect dug a brooding chamber for its intended offspring. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

This is what a fossil insect cocoon looks like in an outcrop. Sometimes a burrow would be connected to the cocoon, showing where the original mother insect dug a brooding chamber for its intended offspring. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

A rare piece of dinosaur bone that actually looks like a bone, even to an untrained eye. Although this one is white, the dinosaur bones in the Two Medicine Formation varied wildly in their colors. So spotting these fossils was more a matter of looking for both a shape and texture that translate into “bone.” (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

A rare piece of dinosaur bone that actually looks like a bone, even to an untrained eye. Although this one is white, the dinosaur bones in the Two Medicine Formation varied wildly in their colors. So spotting these fossils was more a matter of looking for both a shape and texture that translate into “bone.” (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

This is more what most dinosaur bones looked like when I found them in the field area. You probably spotted the big chunk right away, but how about the smaller ones that tend to blend in with the non-dinosaur-bone rocks around them? (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

This is more what most dinosaur bones looked like when I found them in the field area. You probably spotted the big chunk right away, but how about the smaller ones that tend to blend in with the non-dinosaur-bone rocks around them? (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Here’s another example of how fossil tracks are not like modern ones in size, shape, and how it’s preserved. This is a three-toed dinosaur track (probably made by a hadrosaur), but it was originally made in mud, then sand filled in the track-sized hole to make a natural cast, which 75 million years later weathered out so that it’s sitting by itself on the eroded surface of a mudstone. What’s the scale? My boot’s a size 8 1/2 (men’s). Yes, I felt a little inadequate. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Here’s another example of how fossil tracks are not like modern ones in size, shape, and how it’s preserved. This is a three-toed dinosaur track (probably made by a hadrosaur), but it was originally made in mud, then sand filled in the track-sized hole to make a natural cast, which 75 million years later weathered out so that it’s sitting by itself on the eroded surface of a mudstone. What’s the scale? My boot’s a size 8 1/2 (men’s). Yes, I felt a little inadequate. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

What does a natural sandstone cast of a dinosaur track look like when it’s still in outcrop? Look for a lump on the bottom of a sandstone bed. From a side view, you might then see a couple of “toes” pointing in one direction, like in this one: the central toe is to the left and one of the outer toes is on the side, clser to you. Note how the sandstone bed also has a few open invertebrate burrows in it, too. Ichnobonus! (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

What does a natural sandstone cast of a dinosaur track look like when it’s still in outcrop? Look for a lump on the bottom of a sandstone bed. From a side view, you might then see a couple of “toes” pointing in one direction, like in this one: the central toe is to the left and one of the outer toes is on the side, clser to you. Note how the sandstone bed also has a few open invertebrate burrows in it, too. Ichnobonus! (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Check out this big piece of, well, dinosaur coprolite. These trace fossils contained blackened (carbonized) wood fragments that originally passed through the gut of a dinosaur (probably a hadrosaur), and were later cemented by calcite. But you had to look at them doubly, because some of these trace fossils included their own trace fossils made by insects, namely dung beetle burrows. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Check out this big piece of, well, dinosaur coprolite. These trace fossils contained blackened (carbonized) wood fragments that originally passed through the gut of a dinosaur (probably a hadrosaur), and were later cemented by calcite. But you had to look at them doubly, because some of these trace fossils included their own trace fossils made by insects, namely dung beetle burrows. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

You’ve heard of ‘Field of Dreams’? This is a ‘Field of Feces.’ The ground here is adorned with dinosaur coprolites, which are weathering out of the mudstone and breaking apart on the surface. This serves as a good example of how once you know what the dinosaur coprolites look like in this area, you’re less likely to just walk by them, singing “Where Have All the Coprolites Gone?”. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

You’ve heard of ‘Field of Dreams’? This is a ‘Field of Feces.’ The ground here is adorned with dinosaur coprolites, which are weathering out of the mudstone and breaking apart on the surface. This serves as a good example of how once you know what the dinosaur coprolites look like in this area, you’re less likely to just walk by them, singing “Where Have All the Coprolites Gone?”. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

The Two Medicine Formation is famous for its dinosaur eggs and babies, but even more common than those are bits and pieces of dinosaur eggshells. These show up as black flakes on ground surfaces and sometimes in a rock, which you then must distinguish from all other black flakes that are not dinosaur eggshells. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

The Two Medicine Formation is famous for its dinosaur eggs and babies, but even more common than those are bits and pieces of dinosaur eggshells. These show up as black flakes on ground surfaces and sometimes in a rock, which you then must distinguish from all other black flakes that are not dinosaur eggshells. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Can you find the dinosaur eggshell in this photo? I’ll bet the answer was “yes,” but I made it a little easier for you by cropping the photo, placing the eggshell near the center of the image, and oh yea, showing you what typical eggshells look like in the previous photo. Now think about detecting this bit of eggshell from a standing height and while walking. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Can you find the dinosaur eggshell in this photo? I’ll bet the answer was “yes,” but I made it a little easier for you by cropping the photo, placing the eggshell near the center of the image, and oh yea, showing you what typical eggshells look like in the previous photo. Now think about detecting this bit of eggshell from a standing height and while walking. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

After viewing the photos and reading the descriptions, do you think you could recognize each of these fossils if you were somehow magically transported to the Two Medicine Formation in Montana?

The likely answer to that question is, maybe, maybe not. For instance, despite all of my previous paleontological and geological field experience, it took me about two weeks of being in the field before I started accurately identifying dinosaur bones and eggshells. This humbling situation gave me a renewed appreciation for the people who regularly work in the Two Medicine Formation, but also imparted a lesson about taking the time to learn from misidentified burrows, cocoons, coprolites, bones, and eggshells in it. Most things I saw in the Two Medicine were not these fossils, meaning my ways of seeing had to become more discriminating over time.

Thus given enough practice and “dirt time” seeking fossil in the field and correcting your mistakes – preferably with an expert peer-reviewing your finds beside you – the fossil visions will come to you. Then, next thing you know, you start noticing more of what you didn’t see before, expanding your consciousness of the lives that preceded your own.

* * *

Many thanks to Dr. David Varricchio for inviting me to be part of his NSF-sponsored research project in the Two Medicine Formation this summer, and by extension, my deep appreciation to Montana State University and Museum of the Rockies for their logistical support at Camp Makela. May it have many more successful field seasons.

The Seven Samurai of paleontology at Camp Makela, ready for action in the Two Medicine Formation of central Montana. These ruffians/malcontents/Guardians of the Cretaceous Galaxy are otherwise known as (left to right): Ulf, Jared, me, Ashley, Emmy, Paul, and Eric. (Photograph and choreography by Ruth Schowalter.)

The Seven Samurai of paleontology at Camp Makela, ready for action in the Two Medicine Formation of central Montana. These ruffians/malcontents/Guardians of the Cretaceous Galaxy are otherwise known as (left to right): Ulf, Jared, me, Ashley, Emmy, Paul, and Eric. (Photograph and choreography by Ruth Schowalter.)

For more about these people and other human connections between the paleontological research that took place in the Two Medicine Formation – and told from a non-paleontological perspective – go to Cretaceous Summer 2014, which had links to four blog posts done on site by my wife Ruth Schowalter. Also be sure to check out Brad Brown’s blog post from the Burpee Museum of Natural History about his experiences at the field site, Just What the Doctor Ordered: Two Medicine Delivers High Biodiversity in a Low Profile Area.