When you hear the word “shrimp,” you probably picture those that show up in grocery stores and restaurants throughout the world, which are then consumed voraciously by their terrestrial admirers. Also, some recent attention has been given to mantis shrimp, and deservedly so, because they are among the most gorgeous and terrifying of marine invertebrates today. But there are other marine crustaceans bearing the name “shrimp” that are neither gracing seafood buffets nor awesome predators, yet are worthy of our adoration, documentary films, and epic songs, the latter of which will be no doubt performed on Eurovision 2014. Yes, you guessed it: I’m talking about ghost shrimp.

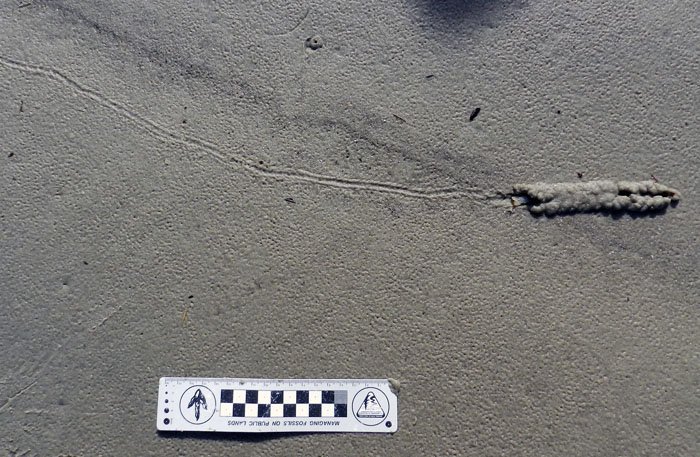

What’s this? We’re looking down on the surface of a Georgia beach at low tide. The collapsed top of a ghost shrimp burrow is in the lower left, but it’s connected to a trackway, which ends in a shallow horizontal burrow, which holds the maker of all three types of traces. Lots of other ghost-shrimp burrow tops are in the upper part of the photo, too. Life doesn’t get much better than this for an ichnologist. You may now envy me. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia; scale in centimeters. )

What’s this? We’re looking down on the surface of a Georgia beach at low tide. The collapsed top of a ghost shrimp burrow is in the lower left, but it’s connected to a trackway, which ends in a shallow horizontal burrow, which holds the maker of all three types of traces. Lots of other ghost-shrimp burrow tops are in the upper part of the photo, too. Life doesn’t get much better than this for an ichnologist. You may now envy me. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia; scale in centimeters. )

Why ghost shrimp? Because they can burrow like nobody’s business. Take a typical ghost shrimp in the Bahamas or the Caribbean, such as Glypterus acanthochirus. This crustacean is only about 10-cm (4-in) long, but if it lives for eight years and burrows continuously through that time, it will have processed a cubic meter of sediment. Individual ghost-shrimp burrows can go as deep as 5 m (16 ft). These would be like a human shoveling more than a cubic kilometer of dirt, or a vertical shaft about 100 m (330 ft) deep, but without a shovel, backhoes, augers, drilling rigs, or other tools. These vertical shafts then connect with extensive branching tunnels, making complicated networks in the sand and mud below the level of the low tide. Now multiply that industriousness by millions, and we’re talking about enormous volumes of sediment processed by ghost shrimp in their respective shallow-water environments. Ghost shrimp are like the ants of the ocean, only not as organized: no queens, workers, soldiers, or other divisions of labor, just lots of individual shrimp burrowing, eating, mating, and defecating.

Every one of these holes is the top of an occupied ghost-shrimp burrow. Now imagine meters-long vertical shafts from each of these going down into the beach sand, then turning into branching horizontal networks of such grandeur, they would further embarrass naked moles rats, which are already apologizing for how they look. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia. Human foot (upper right), still attached to human, for scale.)

Every one of these holes is the top of an occupied ghost-shrimp burrow. Now imagine meters-long vertical shafts from each of these going down into the beach sand, then turning into branching horizontal networks of such grandeur, they would further embarrass naked moles rats, which are already apologizing for how they look. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia. Human foot (upper right), still attached to human, for scale.)

Ghost shrimp share a common ancestor with crabs, lobsters, crayfish, and shrimp, all of these having four pairs of walking legs and one pair of claws. (Mantis shrimp are actually not true shrimp – or even decapods – but stomatopods.) Ghost shrimp are also known by marine biologists and ichnologists as callianassid shrimp, belonging to an evolutionarily linked group (clade), Callianassidae.They burrow through sand and mud using their front two claws, but also carry sediment on their other legs. Ghost shrimp are also well-known for depositing much of the mud on Georgia beaches as elegantly packaged little cylindrical fecal pellets. These bear enough of a resemblance to “chocolate sprinkles” on cupcakes that they become tempting to sample, until you remember that they’re, like, you know, fecal.

Ghost-shrimp fecal pellets, each about 5 mm long, and recently ejected by a ghost shrimp through the top of the burrow, which is the little hole just to the right. If you use them with any cupcake recipes, let me know how that worked for you. (Photo taken by Anthony Martin on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Ghost-shrimp fecal pellets, each about 5 mm long, and recently ejected by a ghost shrimp through the top of the burrow, which is the little hole just to the right. If you use them with any cupcake recipes, let me know how that worked for you. (Photo taken by Anthony Martin on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Geologists love ghost shrimp, too, because of how their burrows are so numerous, fossilize easily, and are sensitive shoreline indicators. I wrote about this before with regard to how geologists in the 1960s were able to map ancient barrier islands of the Georgia coastal plain by looking for trace fossils of these burrows. Since then, geologists and paleontologists have identified and applied these sorts of trace fossils worldwide, and in rocks from the Permian Period to the Pleistocene Epoch.

I could prattle on about ghost shrimp and their ichnological incredibleness for the rest of the year, but will spare you of that, gentle reader, and instead will get to the point of this post. Just when I thought I’d learned nearly everything I needed to know about ghost-shrimp ichnology, one shrimp decided I needed to have my eyes opened to some traces I had never seen them make before just a few months ago. I mentioned these traces briefly in a previous blog post, when I was teaching undergraduate students from my barrier-islands class on Jekyll Island (Georgia) in mid-March. They were tracks and a shallow horizontal burrow made on the surface on the northernmost beach of Jekyll Island, and they were made by a ghost shrimp. How do I know they were made by a ghost shrimp? Well, maybe because they had a ghost shrimp attached to them, but that’s beside the point.

A close-up of the left side of the trackway shows more clearly how it definitely is connected to the funneled top of a burrow. The trackway shows small pointed impressions and a central groove in places, showing that this is an animal with legs and a tail, respectively. The irregular path of the trackway is a record of pauses, where the trackmaker stopped briefly before moving on. The body length of the tracemaker is subtly revealed along the way too, but explaining that would require a more advanced lesson in ichnology. So maybe another time. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

A close-up of the left side of the trackway shows more clearly how it definitely is connected to the funneled top of a burrow. The trackway shows small pointed impressions and a central groove in places, showing that this is an animal with legs and a tail, respectively. The irregular path of the trackway is a record of pauses, where the trackmaker stopped briefly before moving on. The body length of the tracemaker is subtly revealed along the way too, but explaining that would require a more advanced lesson in ichnology. So maybe another time. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

The right side of the trackway, ending in a short and shallow horizontal tunnel, just under the sandy beach surface. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

The right side of the trackway, ending in a short and shallow horizontal tunnel, just under the sandy beach surface. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

The trackway and tail-trail ends in a tunnel with a thin roof of sand. The bilobed pattern was made by the claws and other legs on either side moving sand up and around the body of the tracemaker. Notice the roof collapsed a little on the right, and that its tail is sticking out on the left: kind of like hiding under a too-short blanket. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

The trackway and tail-trail ends in a tunnel with a thin roof of sand. The bilobed pattern was made by the claws and other legs on either side moving sand up and around the body of the tracemaker. Notice the roof collapsed a little on the right, and that its tail is sticking out on the left: kind of like hiding under a too-short blanket. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

Ta-da – the tracemaker revealed! I’m fairly sure this is a Georgia ghost shrimp (Biffarius biformis), but would appreciate all of those marine biologists out there to correct me if I’m wrong. (And not those fake marine biologists, either.) Rest assured, after showing it to my students and allowing them to photograph it, I put it back in the ocean, where it burrowed happily ever after. Unless it died, that is. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

Ta-da – the tracemaker revealed! I’m fairly sure this is a Georgia ghost shrimp (Biffarius biformis), but would appreciate all of those marine biologists out there to correct me if I’m wrong. (And not those fake marine biologists, either.) Rest assured, after showing it to my students and allowing them to photograph it, I put it back in the ocean, where it burrowed happily ever after. Unless it died, that is. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

What truly amazed me about these traces, though, was their rarity. As I shared with my students, in more than 15 years of field work on the Georgia coast, I had never seen anything like this sequence of traces. Even better, the tracemaker was right there, and like the period at the end of a sentence in the story.

Furthermore, the story told by these traces was that something must have threatened the life of this shrimp to cause it to behave in such an unusual way. These shrimp almost never see the light of day, and prefer to stay deep in their burrows, away from the prying eyes and beaks of shorebirds, fish, and other predators. Consequently, they remain largely invisible to humans; hence the “ghost” part of their nickname. This means something very bad must have happened to this one in its burrow, prompting it to abandon its refuge and expose itself so vulnerably. It would be like a fire forcing people out of their fortified underground bunkers, but when they know tyrannosaurs are lurking just outside. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t, but something in this ghost shrimp’s evolutionary program made it take the path of the lesser damned.

What happened? Did a predator find its way into the burrow and chase it out? Was it a chemical cue of some sort, like oxygen-poor water flooding into the bottom of its burrow? Was it competition from another ghost shrimp, evicting it from its home? Was it a mate that decided it had enough of sharing this burrow and needed some “alone time,” or took up with another more comely shrimp? I don’t know, but it made for a good little mystery, yet another posed by life traces on a Georgia beach, and one I was delighted to discover and share with my students on Jekyll Island.