On the other hand, I sometimes think that general & popular Treatises are almost as important for the progress of science as original work.

– Charles Darwin, in a letter to Thomas Huxley, written in his home (Down House) on January 4, 1865

A combined blessing and burden that comes with travel, especially to new places, is the memory we carry of other places. The blessing part comes from the opportunity to connect previously disparate bodies of knowledge and experiences. This is always exciting for anyone who likes that sort of thing, while also satisfying purported promoters of “interdisciplinarity” (which was probably not a word until academia invented it, then pretended to reward those who practice it). On the other hand, the burden is that these thoughts of previous places can act as a veil, obscuring or overlaying our perception of novel sensations. In extreme cases, these remembrances can smother original ideas, especially if the places of our past are idealized and held as some worldly standard to which all other things must be compared.

What does this roundish stone, lying in the ground of the English countryside south of London, have to do with life traces of the Georgia coast? Good question, and if you’d like the start of an answer, please read on.

What does this roundish stone, lying in the ground of the English countryside south of London, have to do with life traces of the Georgia coast? Good question, and if you’d like the start of an answer, please read on.

This Janus-like duality of travel occurred to me after my wife (Ruth) and I left Georgia for a few weeks of vacation in the United Kingdom, yet once there, I thought about my original home of Indiana and the barrier islands of Georgia. Ruth had never been to the U.K., and I hadn’t visited since attending an ichnology conference and field trip in Yorkshire, held in 1999. Fortunately, Ruth has a friend on the northeastern side of London who generously offered us a place to stay before we headed elsewhere. This refuge gave us a few days to learn what London had to offer us while we otherwise adjusted to cultural and temporal differences.

Among the myriad of educational opportunities in the London area is one that had been on my mind for quite a while, thanks to my writing about the Georgia coast. This was an intended visit to Down House, the former home of Charles Darwin and his family. Down House is located in a rural setting of the greater London area – Downe Village in the former parish of Kent – well southeast of Big Ben and all of the other typical touristy trappings of downtown London. Still, it can be visited via public transportation, which became doable for us Yanks once we figured out the needed connections in the intricate rail and bus system weaving throughout the London area.

From where we were staying, it took us nearly two hours to reach Down House. It was a mildly aggravating sojourn by train and bus, but made much better once we realized that driving there in London traffic with a hired car would have been far worse for both us and other people sharing the road (or sidewalk, as it may be). After our bus dropped us off in Downe Village, we saw a small sign pointing the way to Down House, and walked for 15 minutes on a quiet, country road before reaching our goal, a stroll only occasionally interrupted by brief terror induced when cars approached from the direction opposite of our expectations.

When you step off the bus in Downe Village, this is one of the few clues that you’re near Darwin’s home, a place where scientific thought and human history changed in a big way.

A signpost in Downe Village provides a clue that Darwin has something to do with this area, although some horse named “Invicta” gets equal billing, and “St Mary the Virgin” gets bigger typeface. Still, it was nice to see Darwin’s visage there, too.

A signpost in Downe Village provides a clue that Darwin has something to do with this area, although some horse named “Invicta” gets equal billing, and “St Mary the Virgin” gets bigger typeface. Still, it was nice to see Darwin’s visage there, too.

Blink and you’ll miss it: after walking about 10 minutes down the road, here’s the sign pointing the way to Down House. Personally, I thought it could use a neon fringe, or at least some DayGlo™ colors, but subdued is probably the way Darwin would have liked it.

Blink and you’ll miss it: after walking about 10 minutes down the road, here’s the sign pointing the way to Down House. Personally, I thought it could use a neon fringe, or at least some DayGlo™ colors, but subdued is probably the way Darwin would have liked it.

We were also a little surprised at the subdued signage pointing us in the right direction to our goal, and I mused briefly about the homes of people who had far less impact on the advancement of human knowledge and world perspectives whose homes are accorded far more attention and adulation. (Yes, I’m looking at you, Graceland.)

The front of Down House, the home of Charles Darwin and his family from 1842 and after his death in 1882.

The front of Down House, the home of Charles Darwin and his family from 1842 and after his death in 1882.

Down House is both modest and grand, not palatial at all, but impressive inside. Rooms on the second floor (or first floor, if you live in the U.K.) hold displays with a neatly presented synopsis of Darwin’s life and scientific findings, starting with his little boat journey in 1831-1836 through his grand synthesis of evolutionary principles. The ground floor of the house is more or less restored to the time when the Darwin family lived there, with particular attention paid to Mr. Darwin’s study, which was his main writing and experimentation room, or what modern-day scientists might call his “research space.” This is where On the Origin of Species and most other books of his were born. Infused with a purely fan-boy sort of joy, I was thrilled to be in the same place where many of his revolutionary ideas about evolution became expressed through words.

However, one item in the family living room (drawing room) intrigued me in a special way. It was a piano. This object was certainly used for the enjoyment of Darwin family members and guests, with the degree of delight of course depending on the proficiencies and musical choices of whoever played it. But then I was reminded – by the disembodied voice of Sir David Attenborough, no less – that this was not just a musical instrument, but also a scientific tool. (Disappointingly, Sir Attenborough volunteered this information in a recorded audio tour provided with admission to Down House, not through clairvoyance in a Sir Arthur Conan Doyle sense.) On this piano in the room and in the nearby Down House backyard are the places where Darwin conducted some of the earliest quantitative experiments in the behavioral ecology and neoichnology of terrestrial infauna. Or, in plain English, Darwin used this piano and a few other tools to measure and test the behavior of earthworms as tracemakers in soil.

The rear of Down House, with the two windows to the left looking into the drawing room, where the Darwin family piano is located. Unfortunately, photographs are not allowed in the interior of Down House, hence the external, voyeuristic perspective.

The rear of Down House, with the two windows to the left looking into the drawing room, where the Darwin family piano is located. Unfortunately, photographs are not allowed in the interior of Down House, hence the external, voyeuristic perspective.

Darwin enthusiasts know well that the last book Darwin wrote was about a personal passion of his, the biology and behavior of earthworms. This book, titled The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms with Observations on Their Habits (1881), encapsulates many observations and conclusions he made from his long-term study of the oligochaete annelids that lived abundantly in the backyard and gardens of Downe House. As some biographers have noted, Darwin became quite a homebody after his years of voyaging on The Beagle, and he stayed close to Down House for much of his life after moving there in 1842. Nonetheless, this geographically restricted lifestyle did not mean he stopped inquiring about the natural world around him. On the contrary, he carried out intensive studies in and just outside of Down House, some of which dealt with earthworms, a subject that interested him for more than half of his life.

Darwin’s wonderment at worms was jump-started by something he noticed nearly thirty years after he innocuously tried to improve the soil in the pasture behind Down House. Told that he could get rid of mossy areas by laying down cinders and chalk, he obediently did so, and checked those same areas 29 years afterwards. It turned out the anomalous sediments had been buried about 18 cm (7 in) below the surface.

Darwin soon suspected this surface was newly made, formed by generations of earthworms bringing up soil over the preceding three decades. Through the technical support of his son Horace, an engineer, Darwin began to measure just how much earth an earthworm could worm. He already knew that earthworms burrowed through, consumed, and defecated sediment, which resulted in thoroughly mixed and chemically altered soils. So using his geologically inspired sense of time and rates of processes, he also rightly imagined that the daily activities of earthworms, multiplied by millions of worms and enough years, changed the very ground underneath his feet in a way so that it, well, evolved.

Ever the good scientist, though, Darwin tested this basic idea through experimentation. His assessment was accomplished through a precise measuring device invented by his son and flat, circular rocks, nicknamed wormstones, which were set out in the backyard of Down House. Based on my visual and tactile examination of the one wormstone that still lies outside of Down House, it looked like a quartz sandstone. However, out of respect for it and its ichnological and historical heritage, I did no other tests of its composition.

One of Darwin’s original “wormstones” (foreground center) placed in a pastoral setting behind Down House. Paleontologist Barbie (just behind the wormstone), who has accompanied me for much field work on the Georgia coast, helpfully provides scale.

One of Darwin’s original “wormstones” (foreground center) placed in a pastoral setting behind Down House. Paleontologist Barbie (just behind the wormstone), who has accompanied me for much field work on the Georgia coast, helpfully provides scale.

Close-up view of wormstone, showing three metal slots set into a central ring and two rods, which provided the datum for measuring change in the wormstone’s depth over time. £10 note (with Darwin’s portrait on the right) for scale.

Close-up view of wormstone, showing three metal slots set into a central ring and two rods, which provided the datum for measuring change in the wormstone’s depth over time. £10 note (with Darwin’s portrait on the right) for scale.

The experiment was elegantly simple. Using a device invented by Horace in 1870 (illustrated below, and photo here), the surface of the wormstone was measured relative to the height of the surrounding soil surface. This change in relative horizon was discerned by fitting the device on three metal slots that had been added to the edge of a central hole in the wormstone. Metal rods inserted through this same hole were connected to underlying bedrock, ensuring that these would stay stationary as worms churned the surrounding soil. Thus these rods acted as a horizontal datum through which any changes in the ground surface could be compared.

Illustration of Horace Darwin’s “wormstone measuring instrument,” with “K” pointing to where the instrument was placed to contact with the metal rods; the change with each measurement over time between this and “A” (a metal ring) would then show how much the stone had sunk downward. My source of this figure is from an online PDF by the Bromley Partnerships, Discover Darwin: An Education Resource for Key Stage Two, but its primary source is not cited there, and I could not otherwise find an attribution.

Illustration of Horace Darwin’s “wormstone measuring instrument,” with “K” pointing to where the instrument was placed to contact with the metal rods; the change with each measurement over time between this and “A” (a metal ring) would then show how much the stone had sunk downward. My source of this figure is from an online PDF by the Bromley Partnerships, Discover Darwin: An Education Resource for Key Stage Two, but its primary source is not cited there, and I could not otherwise find an attribution.

Darwin figured that the burrowing activity of earthworms underneath the stone, as well as sediment deposition at the surface as fecal castings, would result in the stone “sinking” over time, becoming buried from below. He was right. Using the wormstone and Horace’s measuring device, he calculated the approximate rate of sinking (2.2 mm/year). This was also a measure of soil deposition, which he attributed to earthworms depositing the sediment through fecal castings. Extrapolating these results further, he estimated that 7.5 to 18 tons (6.8-16.4 tonnes) of soil were moved by worms in a typical acre (0.4 hectares) of land.

Something very important to remember in Darwin’s approach to this study was that he was not just a biologist, but also an excellent geologist, taught early in his career – and later befriended – by one of the founders of modern geology, Charles Lyell. Consequently, he had a long-term view of how small, incremental changes every year added up to big changes over time. Or, to put it in Darwin’s own words (The Formation of Vegetable Mould, p. 6), when he responded to a critic claiming that earthworms were too small and weak to have any large-scale effect on their surroundings:

Here we have an instance of that inability to sum up the effects of a continually recurrent cause, which has often retarded the progress of science, as formerly in the case of geology, and more recently in that of the principle of evolution.

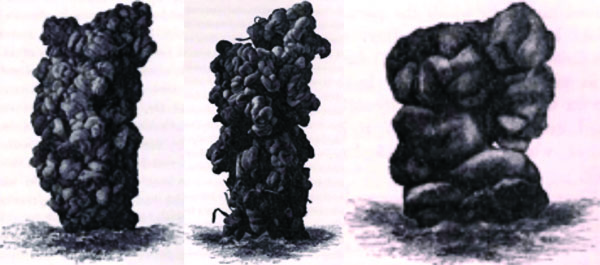

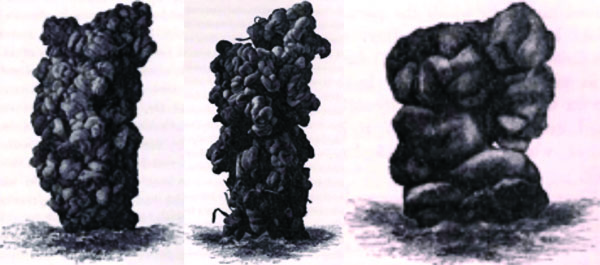

Darwin wasn’t just a quantitative ichnologist, but he also described and illustrated some of the traces made by earthworms, such as their burrows, aestivation chmabers, fecal pellets, and turrets made by their fecal casts. (Much later, in 2007, South American paleontologists described fossil examples of fecal pellets and aestivation chambers from Pleistocene rocks of Uruguay.) Darwin even noted the orientations and species of leaves earthworms pulled into burrows to plug these (p. 64-82), then he independently tested these results with pine needles and triangles of paper (p. 82-90)!

Illustrations of turrets made by fecal pellets of earthworms, in The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms with Observations on Their Habits (1881): from left to right, Figure 2 (p. 107), Figure 3 (p. 124), and Figure 4 (p. 127).

In short, Darwin, through combining his vast knowledge of biology with geological principles, had all the right stuff to make for a formidable ichnologist. Even better, he was keenly interested in the ichnological processes happening just outside his house, and didn’t feel the need to take a long boat trip to watch these processes in some far-off, exotic land. Unknowingly, he was also providing an example of how to do “backyard science” long before this term became associated with cost-effective means for introducing children to nature observation.

All of this marvelous research done by Darwin, culminating in his writing a book at Down House that ended up being one of his most popular, leads me to a bit of a mini-rant, followed by my connecting this science to my homes of Indiana and Georgia, and ending with a message of hope, if I may.

Darwin’s earthworm research epitomized the sort of long-term, DIY experimentation that seemingly only Darwin could have done, and in his day. In contrast, to show how far science has changed since his time, the current profit-oriented business model afflicting modern research universities might have demanded Darwin write a multi-million dollar (or pound) grant to conduct this study. (I suppose the piano would have been the most expensive item on the equipment list, and the wormstones the least.)

Moreover, in this hypothetical scenario, Darwin only could have written such a grant after “pre-confirming” most of his results by publishing a series of research papers. And not just by publishing these papers, but also by making sure they were in prestigious journals, most of which would require expensive subscriptions to read, ensuring that only a small handful of people would read about his work. (A book written for a popular audience? Please.) Had Darwin been a young man, the completion of a 30-year-long study also would have depended on whether he was granted tenure early on. This likely would have been decided by people with little or no expertise in geological processes, earthworms, and bioturbation, but who could certainly count grant revenue and compare journal impact factors.

Fortunately, though, Darwin was independently wealthy, well established as a senior scientist, and never had to worry about tenure or other such trivial matters. Instead, he could just focus on studying his much beloved worms, then think of how to share his vast knowledge of them with a broader audience. Darwin never used the word “ichnology” in his writings, let alone “neoichnology,” and he wrote a book on this topic for natural-history enthusiasts, rather than through a series of research papers published in inaccessible journals. Nonetheless, in his own way, he surely advanced the popularization of ichnology through his slow, deliberate, careful, and imaginative methods, which he combined with a desire to communicate these results to all who were interested.

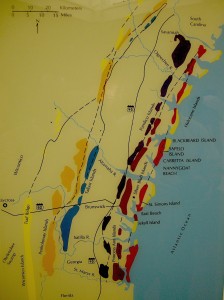

How does all of this link with Indiana and Georgia? Well, Darwin’s “backyard science” reminded me of how I, like many naturalists of a certain generation, grew up learning about nature through what was in my own backyard. Today I have no doubt that my fascination with the behavior and ecology of insects, plants, and yes, earthworms in my Indiana backyard all contributed to a subsequent desire to do science outside as an adult. To satisfy this urge, I later picked geology as my main subject of study, but also took advantage of my biological leanings by concentrating on ichnology in graduate school. My living in Georgia since 1985 and other serendipitous events then eventually led to my writing a book about traces of the Georgia barrier islands (being published through Indiana University Press). In one chapter of this book, when I introduce earthworms as tracemakers, I made sure to write at least a few pages about Mr. Darwin and his experiments with earthworms. So although Darwin never traveled to Indiana or the Georgia coast, I carried my boyhood and adult experiences of both places in my mind to his former home.

Now here’s the hopeful message (not to be confused with a “hopeful monster“). Lots of field-oriented scientists spend much of their time outside for their research, and many require only modest amounts of money for their studies. So what they have begun to do is side-step the reigning corporate mentality influencing so-called “big science” at universities, while also making active attempts to better connect their research with more people than their academic peers. Through organized efforts like The SciFund Challenge and other crowd-sourcing methods, scientists are seeking small personal donations from the public, allowing them to better focus on their research, rather than spending much time, energy, and angst in writing massive research grants that have little chance of being funded. Thus much like earthworm castings, these donations add up over time and provide rich, fertile ground for conducting basic science. (OK, maybe not the best metaphor, but you get the point.)

Another facet of this research is the stated commitment of scientists to report their research progress through blogs, then publish their peer-reviewed results in open access journals, which provide articles free for anyone with an Internet connection and curiosity in a scientific subject. All of this means that small investigations with big implications – like Darwin’s study on earthworms – are more likely to happen, and are better assured of reaching a public eager to learn about these sciences, while giving the opportunity for people to witness the direct benefits of their investments.

So how does the Darwin family piano relate to his study of earthworms? Do the southeastern U.S., earthworms, and Darwin’s study of their behavior somehow intersect? In answer to the first question, it’s interesting, and in answer to the second, yes. But an explanation of both will have to wait until next time.

In the meantime, if you go out for a walk later today, pay attention to the ground beneath you, and think of how it reflects an ichnological landscape, a result of collective traces made by those “lowly” earthworms, and how Charles Darwin clearly explained this fact in 1881. For me, it was an honor to stand in the same area where Darwin made his measurements, used his humble instruments, and applied his fine mind; this despite my later realization that I was standing on a new ground surface relative to where Darwin stood. After all, 130 years has passed since his death, meaning the ground had been recycled by descendants of the same earthworms he watched with his appreciative and discerning eyes. All of which makes for a different kind of descent with modification, one that instead reflects an ichnological perspective well articulated and appreciated by Darwin.

Darwin’s “sandwalk,” a walking route behind Down House he often took to help with his thinking, and a visible trace today of Darwin’s legacy as one of the first popularizers of ichnology.

Darwin’s “sandwalk,” a walking route behind Down House he often took to help with his thinking, and a visible trace today of Darwin’s legacy as one of the first popularizers of ichnology.

Further Reading

Darwin, C. 1881. The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms with Observations on Their Habits. John Murray, London: 326 p. (A scan of the original book, converted to a PDF document, is here.]

Pemberton, S. George and Robert W. Frey. 1990. Darwin on worms: the advent of experimental neoichnology. Ichnos, 1: 65-71. (Text for article here.)

Quammen, D. 2006. The Reluctant Mr. Darwin: An Intimate Portrait of Charles Darwin and the Making of His Theory of Evolution. W.W. Norton, New York: 304 p.

Verde, M., Ubilla, M., Jiménez, J.J., and Genise, J.F. 2006. A new earthworm trace fossil from paleosols: aestivation chambers from the Late Pleistocene Sopas Formation of Uruguay. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 243: 339-347.

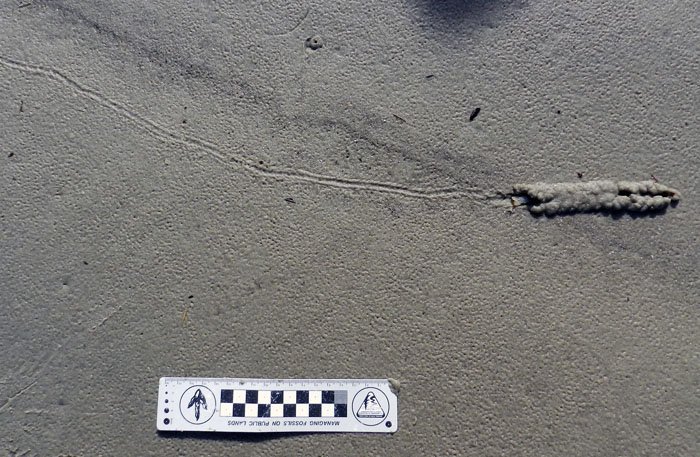

What’s this? We’re looking down on the surface of a Georgia beach at low tide. The collapsed top of a ghost shrimp burrow is in the lower left, but it’s connected to a trackway, which ends in a shallow horizontal burrow, which holds the maker of all three types of traces. Lots of other ghost-shrimp burrow tops are in the upper part of the photo, too. Life doesn’t get much better than this for an ichnologist. You may now envy me. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia; scale in centimeters. )

What’s this? We’re looking down on the surface of a Georgia beach at low tide. The collapsed top of a ghost shrimp burrow is in the lower left, but it’s connected to a trackway, which ends in a shallow horizontal burrow, which holds the maker of all three types of traces. Lots of other ghost-shrimp burrow tops are in the upper part of the photo, too. Life doesn’t get much better than this for an ichnologist. You may now envy me. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia; scale in centimeters. ) Every one of these holes is the top of an occupied ghost-shrimp burrow. Now imagine meters-long vertical shafts from each of these going down into the beach sand, then turning into branching horizontal networks of such grandeur, they would further embarrass naked moles rats, which are already apologizing for how they look. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia. Human foot (upper right), still attached to human, for scale.)

Every one of these holes is the top of an occupied ghost-shrimp burrow. Now imagine meters-long vertical shafts from each of these going down into the beach sand, then turning into branching horizontal networks of such grandeur, they would further embarrass naked moles rats, which are already apologizing for how they look. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia. Human foot (upper right), still attached to human, for scale.) Ghost-shrimp fecal pellets, each about 5 mm long, and recently ejected by a ghost shrimp through the top of the burrow, which is the little hole just to the right. If you use them with any cupcake recipes, let me know how that worked for you. (Photo taken by Anthony Martin on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Ghost-shrimp fecal pellets, each about 5 mm long, and recently ejected by a ghost shrimp through the top of the burrow, which is the little hole just to the right. If you use them with any cupcake recipes, let me know how that worked for you. (Photo taken by Anthony Martin on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.) A close-up of the left side of the trackway shows more clearly how it definitely is connected to the funneled top of a burrow. The trackway shows small pointed impressions and a central groove in places, showing that this is an animal with legs and a tail, respectively. The irregular path of the trackway is a record of pauses, where the trackmaker stopped briefly before moving on. The body length of the tracemaker is subtly revealed along the way too, but explaining that would require a more advanced lesson in ichnology. So maybe another time. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

A close-up of the left side of the trackway shows more clearly how it definitely is connected to the funneled top of a burrow. The trackway shows small pointed impressions and a central groove in places, showing that this is an animal with legs and a tail, respectively. The irregular path of the trackway is a record of pauses, where the trackmaker stopped briefly before moving on. The body length of the tracemaker is subtly revealed along the way too, but explaining that would require a more advanced lesson in ichnology. So maybe another time. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.) The right side of the trackway, ending in a short and shallow horizontal tunnel, just under the sandy beach surface. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

The right side of the trackway, ending in a short and shallow horizontal tunnel, just under the sandy beach surface. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.) The trackway and tail-trail ends in a tunnel with a thin roof of sand. The bilobed pattern was made by the claws and other legs on either side moving sand up and around the body of the tracemaker. Notice the roof collapsed a little on the right, and that its tail is sticking out on the left: kind of like hiding under a too-short blanket. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

The trackway and tail-trail ends in a tunnel with a thin roof of sand. The bilobed pattern was made by the claws and other legs on either side moving sand up and around the body of the tracemaker. Notice the roof collapsed a little on the right, and that its tail is sticking out on the left: kind of like hiding under a too-short blanket. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.) Ta-da – the tracemaker revealed! I’m fairly sure this is a Georgia ghost shrimp (Biffarius biformis), but would appreciate all of those marine biologists out there to correct me if I’m wrong. (And not those fake marine biologists, either.) Rest assured, after showing it to my students and allowing them to photograph it, I put it back in the ocean, where it burrowed happily ever after. Unless it died, that is. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

Ta-da – the tracemaker revealed! I’m fairly sure this is a Georgia ghost shrimp (Biffarius biformis), but would appreciate all of those marine biologists out there to correct me if I’m wrong. (And not those fake marine biologists, either.) Rest assured, after showing it to my students and allowing them to photograph it, I put it back in the ocean, where it burrowed happily ever after. Unless it died, that is. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)