(The following post is one of a series about traces of important invasive species of mammals on the Georgia barrier islands and the ecological effects of these traces. An introduction to this topic from last week is here.)

Perhaps the most charismatic yet problematic of non-native animals on any of the Georgia barrier islands are the wild horses (Equus caballus) of Cumberland Island. These horses are the source of much controversy, which becomes even more apparent whenever anyone tries to apply some actual science to them. So I will talk about them here from my perspective as a paleontologist and geologist in the hope that this will add another dimension to what is often presented as a two-sided and emotional argument.

Ah, the wild horses of Cumberland Island, Georgia, roaming free since the time of the Spanish in a pristine, unspoiled landscape, grazing contently on the sea oats and strolling through the coastal dunes, in perfect harmony with nature. How much of the preceding sentence is wrong? Almost all of it. If you want to find out why, please read on. But if your mind is already made up about the feral horses of Cumberland and you don’t want to hear anything bad said about them, then you might like this site. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Ah, the wild horses of Cumberland Island, Georgia, roaming free since the time of the Spanish in a pristine, unspoiled landscape, grazing contently on the sea oats and strolling through the coastal dunes, in perfect harmony with nature. How much of the preceding sentence is wrong? Almost all of it. If you want to find out why, please read on. But if your mind is already made up about the feral horses of Cumberland and you don’t want to hear anything bad said about them, then you might like this site. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Cumberland Island, much of which is part of the U.S. National Park system as a National Seashore, is the only Georgia barrier island with a population of feral horses. Nevertheless, despite their uniqueness and fame – the latter figuring as key attractions in advertisements about Cumberland and inspiring dreamy book titles – their origins remain murky. One of the recurring romanticized claims is that these horses descended from livestock brought there by Spanish expeditions in the 16th century. This idea is reassuring to the people who repeat it for two reasons:

(1) It establishes horses as living in the landscape for a long time (especially by American standards), meaning that their presence there now is considered “natural.”

(2) It lends itself to the comforting thought that the horses connect to a European cultural heritage, putting an Old World imprint on a New World place.

However, once said enough times, such just-so stories become faith-based and any evidence contradicting them is not tolerated. Thus even when genetic studies of the Cumberland horses show they are not appreciably different from populations of horses on other islands of the eastern U.S. (arguing against a purely Spanish origin), any questioning of the stated premise – in my experience – provokes angry responses from its defenders.

I suspect this virulent reaction is a direct result of challenging both the “naturalness” and “cultural heritage” of the horses on Cumberland. In reality, though, these are opposing values. After all, an admission that these feral horses came from European stock at any point during the past 500 years supports how they clearly do not belong on Cumberland Island, or anywhere else in the Western Hemisphere if we’re talking about the last 10,000 years or so. In other words, the point is moot whether the current horse population originated in the 16th, 17th, 18th, 19th, or 20th century, or is a mixture of older and newer stock. If only horses could talk, then we would know for sure. (A detailed history of the horses on Cumberland Island is provided here for anyone interested in learning more about this.)

Arguments of heritage aside, these horses are newcomers in a geological and ecological sense. The fossil record of the modern Georgia barrier islands backs this up, as some of the islands (including Cumberland) have sediments more than 40,000 years old, but none have body or trace fossils of horses, or anything like a horse. Although three species of horses were living on the mainland part of North America during the Pleistocene Epoch until their respective extinctions more than 10,000 years ago, none were known to have inhabited any of the barrier islands, Pleistocene or recent. The closest ancient analogue to horses on any of the Georgia barrier islands would have been bison (Bison bison), but their bones are rare. This scarcity leads paleontologists to wonder whether the islands ever had self-sustaining populations of large herbivores.

So with all of that human history and pre-history in mind, the traces made by the feral horses of Cumberland and their ecological effects are exceptional to it and every other Georgia barrier island, and hence worth our attention. Just to keep this simple, I will cover three primary types of traces made by these horses. What these traces all have in common (other than being made by a horse, of course) is the decidedly negative impacts these have on the native plants and animals of Cumberland, including keystone species in the oft-labeled “pristine” ecosystems of the island.

• Tracks and trails – These traces are the abundant and easily spotted on Cumberland, even to someone with little or no training in ichnology. Horses are unguligrade, which means they are walking on their toenails (unguals), and the ungual (more popularly called a hoof) is on a single digit. Hooves make circular to slightly oval compression shapes, but if preserved in the right substrate – like a firm mud or fine sand – they will show a “Pac-Man”-like form. Front-foot (manus) tracks are slightly larger than rear-foot (pes) tracks; manus impressions are 11-14 cm (4.3-5.5 in) long and 10-13 cm (4-5.1 in) wide, whereas pes impressions are 11-13 cm (4.3-5.1 in) long and 9-12 cm (3.5-4.7 in) wide, with variations in size depending on ages of the horses making the tracks.

Trackway of feral horse moving through the coastal dunes of Cumberland Island. Note the diagonal walking pattern and how front- and rear-foot impressions merge to make oblong compound traces.

Trackway of feral horse moving through the coastal dunes of Cumberland Island. Note the diagonal walking pattern and how front- and rear-foot impressions merge to make oblong compound traces.

An important point to keep in mind when tracking horses or any other hoofed animals is that their feet readily cut through sediments and vegetation, leaving much more sharply defined and deeper impressions than padded feet of an equivalent-sized animal. Because Georgia-coast sands contain whitish quartz and darker heavy minerals, these contrasting sand colors help to outline horse tracks on surfaces and in cross-section as deep and sharply defined structures that cut across the bedding.

When asked to think about horses in motion, it might be tempting to imagine them galloping, especially along a beach at sunset. Nonetheless, a horse would tire quickly if it galloped all day, especially for no valid reason. Instead, its normal gait is a slow walk, which causes the rear foot to register partially on top of the front-foot impression, but slightly behind; with a slightly faster walk, the rear foot will exceed the front-foot impression. The overall trackway pattern then is what many trackers call “diagonal-walking,” as the right-left-right alternation of steps can be linked with imaginary diagonal lines. Trackway width, also known as straddle, is about 20-40 cm (8-16 in) if a horse was just walking normally, but narrows noticeably once it starts picking up speed.

Feral-horse tracks on Cumberland Island, a close-up of the same trackway shown in the previous photo. This one was likely doing a slow walk, with indirect register of the rear foot just behind and onto the front-foot impression. The scale (my shoe) is a size 8½ mens. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Feral-horse tracks on Cumberland Island, a close-up of the same trackway shown in the previous photo. This one was likely doing a slow walk, with indirect register of the rear foot just behind and onto the front-foot impression. The scale (my shoe) is a size 8½ mens. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Given enough back-and-forth movement along preferred paths, repeating and overlapping trackways result in trails, which can be picked out as linear bare patches of exposed sand or mud cutting through vegetation. Because horses are much larger than the native white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) on Cumberland, their trails are considerably wider.

Feral-horse trail along the edge of a low salt marsh where they have trampled and overgrazed the smooth cordgrass in that marsh (Spartina alterniflora). (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Cumberland Island.)

Feral-horse trail along the edge of a low salt marsh where they have trampled and overgrazed the smooth cordgrass in that marsh (Spartina alterniflora). (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Cumberland Island.)

• Chew marks – Horses are grazers and low-level browsers, and they eat a wide variety of vegetation on Cumberland. The most important plant species they eat through grazing are smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora), sea oats (Uniola paniculata), and live oak (Quercus virginiana). All three of these plants are keystone species in their respective ecosystems: smooth cordgrass predominates in the low salt marshes, sea oats are the mainstay plants of coastal dunes, and live oaks are the largest and most long-lived trees in the maritime forests. Their effects of horses consuming smooth cordgrass and sea oats is straightforward, as these plants hold in sediments in place keep them from eroding, but how do horses affect live oaks? They eat the seedlings, which means that older oaks are being replaced by younger ones at a slower rate.

Grazing traces consist of clean cuts of vegetation within a vertical swath and over a broad area. Horses, unlike white-tailed deer, have teeth on both their upper and lower jaws, thus they shear plants on the branches, stems, or leaves. In contrast, deer leave more ragged marks, as they only have teeth on their lower jaws and hence have to pull on vegetation to break it off. Horses also can make a browse line, which is an abrupt horizontal line of decreased vegetation at a certain consistent height that more-or-less correlates with the average head height of the horses.

• Dung – During any given stroll on Cumberland, you cannot avoid seeing, smelling, and stepping in horse feces. This abundance of fecal material means that the feces are not being recycled quickly enough into the ecosystems, which implies that native populations of dung beetles are overwhelmed by such abundance. I have seen a few traces of dung beetles in fresh piles of feces, but no matter how hard I have looked, I have yet to witness great thundering herds of beetles rolling balls of dung across the Cumberland Island landscape.

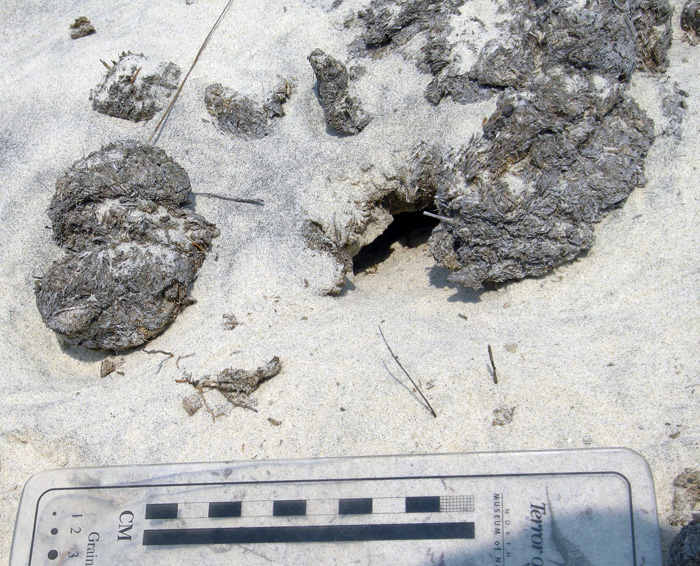

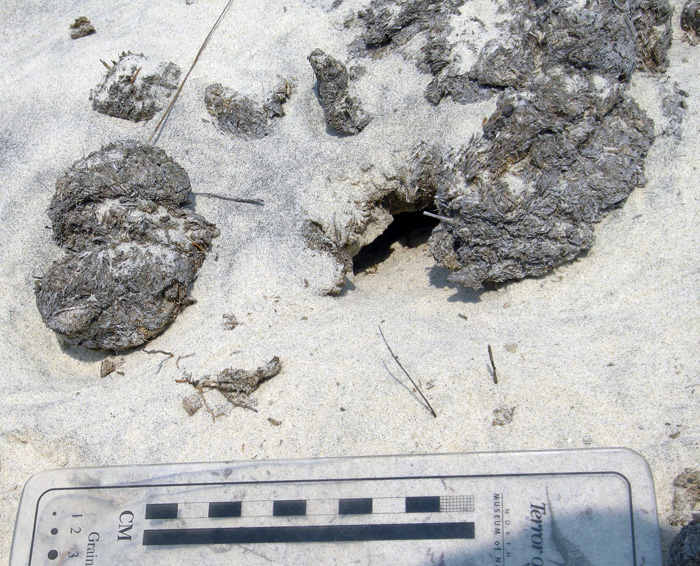

An impressive collection of horse dung, which was probably dropped by a single horse. Note the small holes in the middle, which were likely made by dung beetles that tunneled into this rich supply of food for their offspring.

An impressive collection of horse dung, which was probably dropped by a single horse. Note the small holes in the middle, which were likely made by dung beetles that tunneled into this rich supply of food for their offspring.

Close-up of those probable dung-beetle burrows, some with short trails attached. The white quartz sand sprinkled on top shows how it was pulled up by beetles from underneath the dung pile and onto the top surface, thus giving a minimum depth of the burrows. (Both photographs by Anthony Martin, taken on Cumberland Island.)

Close-up of those probable dung-beetle burrows, some with short trails attached. The white quartz sand sprinkled on top shows how it was pulled up by beetles from underneath the dung pile and onto the top surface, thus giving a minimum depth of the burrows. (Both photographs by Anthony Martin, taken on Cumberland Island.)

One of the more interesting ecological consequences of horse dung I have seen on Cumberland is how it influences the behavior of smaller animals as pellets or piles form a microtopography. For example, on some of the dunes near Lake Whitney on Cumberland – the largest body of fresh water on any of the Georgia barrier islands – I was surprised to see that small lizards – probably skinks – were moving around the dung piles or burrowing under them.

Horse droppings as a part of the landscape for small lizards. Here their tracks, accompanied by tail dragmarks, wind around partially buried feces in a sand dune. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Cumberland Island.)

Horse droppings as a part of the landscape for small lizards. Here their tracks, accompanied by tail dragmarks, wind around partially buried feces in a sand dune. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Cumberland Island.)

Small lizard burrow entrance immediately below a horse pellet, showing its use as a sort of roof. This could probably inspire some clever statement on shingles and, well, you know, but I’ll refrain for now. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Cumberland Island.)

Small lizard burrow entrance immediately below a horse pellet, showing its use as a sort of roof. This could probably inspire some clever statement on shingles and, well, you know, but I’ll refrain for now. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Cumberland Island.)

All three categories of traces – tracks, chew marks, and dung – can be found together in ecosystems wherever horses are trampling, grazing, and defecating, respectively.

So now let’s put on our paleontologist or geologist hats (not to be confused with archaeologist hats) and ask ourselves about the likelihood of such traces making it into the fossil record, and how we would recognize them if they did. Their likelihood of preservation, in order, would be tracks, feces, and chew marks. Tracks would be evident as large compression shapes in horizontal bedding planes or deep disruptions of bedding planes in vertical section. Feces, or their fossil versions called coprolites, might get preserved, although herbivore feces, filled with vegetative material, is less likely to make it into the fossil record compared to carnivore feces, which may have lots of bone material in it. The last of these – chew marks – would be nearly impossible to tell from normal tearing and other degradation of plant material before it became fossilized. Good luck on that.

But could the ecological damage caused by an invasive species, in which the introduction of a species serve as a sort of trace fossil in itself? In the case of horses or ecologically similar animals, subtle changes to the landscape over time might take place. This experiment actually has been done on Assateauge Island (North Carolina), which also has a feral horse population. In areas where horses were excluded by fences, the dunes were on average 0.6 meters (2 ft) feet higher than those of overgrazed and trampled dunes. Geologists conducted another study done on Shackleford Banks (North Carolina) in which they examined areas where fences had separated non-horse from horse-occupied parts of the island. These geologists similarly found that horses caused dunes to be less than 1.5 m (5 ft) high, whereas dunes without horses were as much as 3.5 m (11.5 ft) high. This meant that storms more easily penetrated the barriers provided by coastal dunes, more commonly resulting in storm-washover fans.

This change in the coastal geology of back-dune areas also means that ground-nesting shorebirds will become less common, as their nests and nestlings will be drowned or buried more frequently. Horses also are known to step on shorebird eggs and nests, or can scare away parents from nests, which increases the likelihood of egg or nest predators taking out the next generation of shorebirds.

If any horses made it to the Georgia barrier islands during the Pleistocene and established breeding populations, a geologic sequence following their arrival would look like this, from bottom to top: high dunes suffused with root traces (before horses); lower dunes corresponding with fewer root traces and deep disruptions of bedding (horse tracks); increased numbers of storm-washover fans; and a high salt-marsh. In short, a geologist would see an overall progression from a dune-dominated shoreline to a high salt marsh. Similarly, a paleontologist might see a decrease in root trace fossils and shorebird nests, eggshells, and tracks, possibly culminating in local extinctions of each.

This is your Georgia coast.

This is your Georgia coast.

This is your Georgia coast with horses. Any questions?

This is your Georgia coast with horses. Any questions?

Top panorama is of high-amplitude coastal dunes and well-vegetated back-dune meadows on Sapelo Island, whereas the bottom panorama is of low-amplitude dunes with no appreciable back-dune meadows on Cumberland Island. (Both panoramas based on photos taken by Anthony Martin.)

Based on what we know then, should the feral horses of Cumberland Island be removed? Yes. Will they be removed? Probably not. However, regardless of happens, I will keep teaching about the horses of Cumberland Island and their traces, both as an educator and a concerned citizen. Perhaps with enough awareness, circumstances will change for the better so that Cumberland Island can not only remain a beautiful place, but also will become more like what it was before the arrival of horses there.

(Next week in this series about invasive mammal species of the Georgia barrier islands and their traces, I’ll cover a less inflammatory but still intriguing topic: the feral cattle of Sapleo Island.)

Further Reading

Buynevich, I.V., Darrow, J.S., Grimes, T.A.Z., Seminack, C.T., and Griffis, N. 2011. Ungulate tracks in coastal sands: recognition and sedimentological significance. Journal of Coastal Research, Special Issue 64: 334-338.

De Stoppalaire, G.H., Gillespie, T.W., Brock, J.C., and Tobin, G.A. 2004. Use of remote sensing techniques to determine the effects of grazing on vegetation cover and dune elevation at Assateague Island National Seashore: impact of horses. Environmental Management, 34: 642-649.

Dilsaver, L.M. 2004. Cumberland Island National Seashore: A History of Conservation Conflict. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville, Virginia: 304 p.

Elbroch, M. 2003. Mammal Tracks and Sign: A Guide to North American Species. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: 779 p.

Goodloe, R.B., Warren, R.J., Osborn, D.A., and Hall, C. 2000. Population characteristics of feral horses on Cumberland Island and their management implications. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 64: 114-121.

Sabine, J.B., Schweitzer, S.H., and Meyers, J.M. 2006. Nest Fate and Productivity of American Oystercatchers, Cumberland Island National Seashore, Georgia. Waterbirds, 29: 308-314.

Turner, M.G. 1987. Effects of grazing by feral horses, clipping, trampling, and burning on a Georgia salt marsh. Estuaries and Coasts, 10: 54-60.

Turner, M.G. 1988. Simulation and management implications of feral horse grazing on Cumberland Island, Georgia. Journal of Range Management, 41: 441-447.

After a 45-minute ferry ride to Cumberland Island, the students received a different sort of lecture when naturalist extraordinaire Carol Ruckdeschel – who is writing a book about the natural history of Cumberland Island – met with them and gave them a brilliant overview of the island ecology. She mostly talked with the students about the effects of feral animals on the island, then spent another hour with us in the maritime forest and through the back-dune meadows. It was a real treat for the students and me, and a great way to start the field trip.

After a 45-minute ferry ride to Cumberland Island, the students received a different sort of lecture when naturalist extraordinaire Carol Ruckdeschel – who is writing a book about the natural history of Cumberland Island – met with them and gave them a brilliant overview of the island ecology. She mostly talked with the students about the effects of feral animals on the island, then spent another hour with us in the maritime forest and through the back-dune meadows. It was a real treat for the students and me, and a great way to start the field trip. A leaf-cutter bee trace! Despite my writing about these and illustrating them in my book, these distinctive incisions were the first I can recall seeing on the Georgia barrier islands. These traces were abundantly represented in the leaves of a red bay tree we spotted along a trail through the maritime forest, making for a great impromptu natural history lesson for the students.

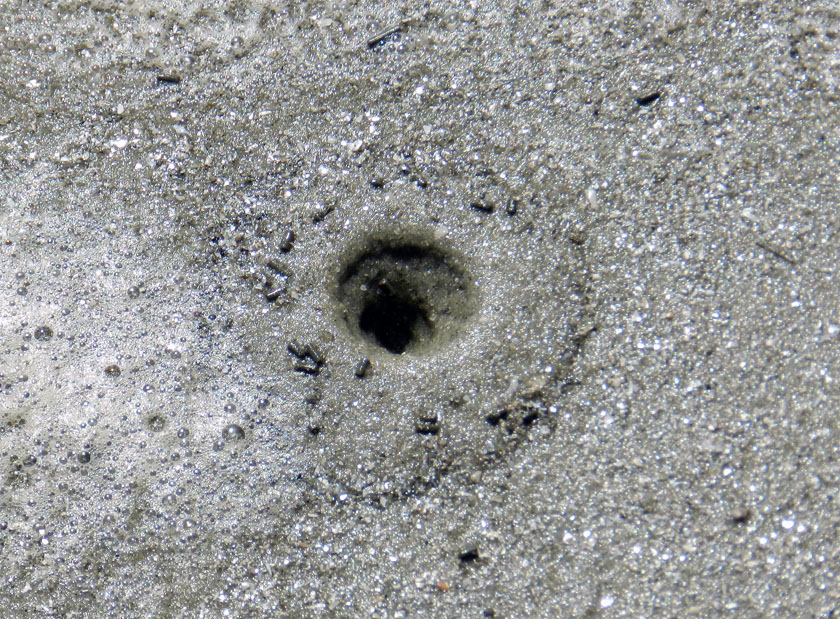

A leaf-cutter bee trace! Despite my writing about these and illustrating them in my book, these distinctive incisions were the first I can recall seeing on the Georgia barrier islands. These traces were abundantly represented in the leaves of a red bay tree we spotted along a trail through the maritime forest, making for a great impromptu natural history lesson for the students. A freshly erupted ghost shrimp burrow on the beach at Cumberland, in which the students were lucky enough to witness the forceful ejection of muddy fecal pellets by the shrimp from the top of its burrow. I mean, really: explain to me how the life of an ichnologist-educator can get any better than that?

A freshly erupted ghost shrimp burrow on the beach at Cumberland, in which the students were lucky enough to witness the forceful ejection of muddy fecal pellets by the shrimp from the top of its burrow. I mean, really: explain to me how the life of an ichnologist-educator can get any better than that? The fine tradition a field lunch, made even more fine by the addition of fine quart sand to our meals, freely delivered by a brisk sea breeze. Did the sand leave any microwear marks on our teeth? I certainly hope so.

The fine tradition a field lunch, made even more fine by the addition of fine quart sand to our meals, freely delivered by a brisk sea breeze. Did the sand leave any microwear marks on our teeth? I certainly hope so. A student is delighted to test my ichnologically based method for finding buried whelks underneath beach sands, and find out that it is indeed correct. (Was there any doubt?) Here she is proudly holding a live knobbed whelk, which I can assure you she promptly placed back into the water once its photo shoot was finished for the day.

A student is delighted to test my ichnologically based method for finding buried whelks underneath beach sands, and find out that it is indeed correct. (Was there any doubt?) Here she is proudly holding a live knobbed whelk, which I can assure you she promptly placed back into the water once its photo shoot was finished for the day. Just to join in the fun, other students decided my “buried whelk prospecting” method required further testing. Let’s just say this student did not disprove the hypothesis, but rather seemed to confirm it, and doubly so. It’s almost as if ichnology is a real science! (Yes, these whelks went back into the water, too.)

Just to join in the fun, other students decided my “buried whelk prospecting” method required further testing. Let’s just say this student did not disprove the hypothesis, but rather seemed to confirm it, and doubly so. It’s almost as if ichnology is a real science! (Yes, these whelks went back into the water, too.) OK, enough about marine predatory gastropods (for now). How about some of the largest horseshoe crabs (limulids) in the world? We found a large deposit of their carapaces above the high-tide mark, some of which were probably molts, but others recently dead. Sadly, though, we did not see any of their traces. Bodies only do so much for me.

OK, enough about marine predatory gastropods (for now). How about some of the largest horseshoe crabs (limulids) in the world? We found a large deposit of their carapaces above the high-tide mark, some of which were probably molts, but others recently dead. Sadly, though, we did not see any of their traces. Bodies only do so much for me. Where do dunes come from? Well, a mother and father dune love each other very much… No wait, wrong story. What happens is that dead cordgrass from the salt marshes washes up onto the beach, where it starts slowing down wind-blown sand enough that it accumulates. Now it just needs some wind-blown seeds of sea oats and other plants to start colonizing it, and next thing you know, dune. Dude.

Where do dunes come from? Well, a mother and father dune love each other very much… No wait, wrong story. What happens is that dead cordgrass from the salt marshes washes up onto the beach, where it starts slowing down wind-blown sand enough that it accumulates. Now it just needs some wind-blown seeds of sea oats and other plants to start colonizing it, and next thing you know, dune. Dude. Ah, a geological tradition in action: comparing actual sand from a real outdoor environment to the sand categories on a handy grain-size chart, and using a hand lens. It’s enough to bring a tear to the eyes of this geo-educator. Or maybe that was just the wind-blown sand.

Ah, a geological tradition in action: comparing actual sand from a real outdoor environment to the sand categories on a handy grain-size chart, and using a hand lens. It’s enough to bring a tear to the eyes of this geo-educator. Or maybe that was just the wind-blown sand. Finally, something that really matters, like ichnology! This is a three-for-one special, too: sanderling feces (left), tracks, and regurgitants (right), the last of these also known as cough pellets. Looks like it had coquina and dwarf surf clams for breakfast.

Finally, something that really matters, like ichnology! This is a three-for-one special, too: sanderling feces (left), tracks, and regurgitants (right), the last of these also known as cough pellets. Looks like it had coquina and dwarf surf clams for breakfast. Wow, more shorebird traces! The tracks are from a loafing royal tern, and it clearly needed to get a load off its mind before moving on with the rest of its day.

Wow, more shorebird traces! The tracks are from a loafing royal tern, and it clearly needed to get a load off its mind before moving on with the rest of its day. Tired of shorebird traces? How about a modern terrestrial theropod? Wild turkey tracks in the back-dune meadows of Cumberland were a happy find, leading to my grilling the students with the seemingly simple question, “What bird made this?” They did not do well on this, but hey, it was the first day, and at least no one said “robin” or “ostrich.”

Tired of shorebird traces? How about a modern terrestrial theropod? Wild turkey tracks in the back-dune meadows of Cumberland were a happy find, leading to my grilling the students with the seemingly simple question, “What bird made this?” They did not do well on this, but hey, it was the first day, and at least no one said “robin” or “ostrich.” Did somebody say “doodlebug?” This long, meandering, and collapsed tunnel of an ant lion (a larval neuropteran, or lacwing) tells us that this insect was looking for prey in all the wrong places.

Did somebody say “doodlebug?” This long, meandering, and collapsed tunnel of an ant lion (a larval neuropteran, or lacwing) tells us that this insect was looking for prey in all the wrong places. Behold, tracks that bespeak of great, thundering herds of sand-fiddler crabs that used to roam the sand flats above the salt marsh. Where have they gone, and will they ever come back? Who knows where the males might be waving their mighty claws? Do the female fiddler crabs suffer from big-claw envy, or are they enlightened enough to reject cheliped-based hierarchies imposed upon them by fiddler-crab society? All good questions, deserving answers, none of which make any sense.

Behold, tracks that bespeak of great, thundering herds of sand-fiddler crabs that used to roam the sand flats above the salt marsh. Where have they gone, and will they ever come back? Who knows where the males might be waving their mighty claws? Do the female fiddler crabs suffer from big-claw envy, or are they enlightened enough to reject cheliped-based hierarchies imposed upon them by fiddler-crab society? All good questions, deserving answers, none of which make any sense. Yes, that’s right, feral horses are really bad for salt marshes. Between overgrazing and trampling, they aren’t exactly what anyone could call “eco-friendly.” My students had heard me say this repeatedly throughout the semester, and Carol Ruckdeschel said the same thing earlier in the day. But then there’s seeing it for themselves, another type of learning altogether.

Yes, that’s right, feral horses are really bad for salt marshes. Between overgrazing and trampling, they aren’t exactly what anyone could call “eco-friendly.” My students had heard me say this repeatedly throughout the semester, and Carol Ruckdeschel said the same thing earlier in the day. But then there’s seeing it for themselves, another type of learning altogether. And the day ended with beautiful ripple marks, beckoning from the sandflat below the boardwalk on our trip back onto the ferry. Even this ichnologist can appreciate the aesthetic appeal of gorgeous physical sedimentary structures.

And the day ended with beautiful ripple marks, beckoning from the sandflat below the boardwalk on our trip back onto the ferry. Even this ichnologist can appreciate the aesthetic appeal of gorgeous physical sedimentary structures.