A first day of field work in the natural sciences can be expected to hold surprises, no matter what type of science is being attempted. Sometimes these are unpleasant ones, such as finding out the fuel gauge in your field vehicle – which you are driving for the first time, and in a remote place – doesn’t work. Other times, you make a fantastic discovery, like a new species of spider, a previously undocumented invasive plant, or a fossil footprint. But sometimes you see something that just makes you scratch your head and say, “What the heck is that?”, or more profane variations on that sentiment.

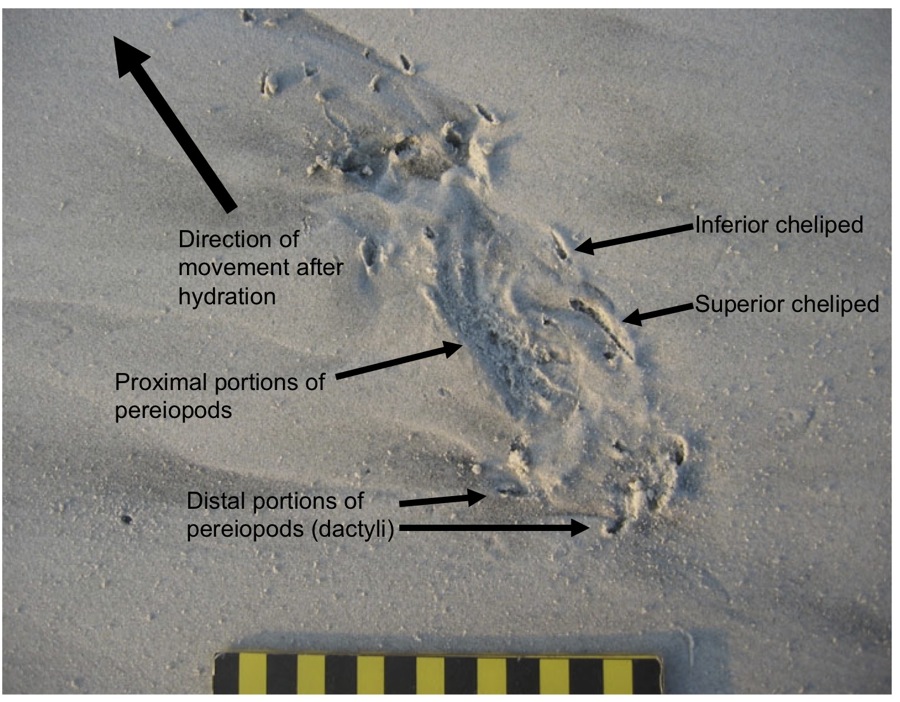

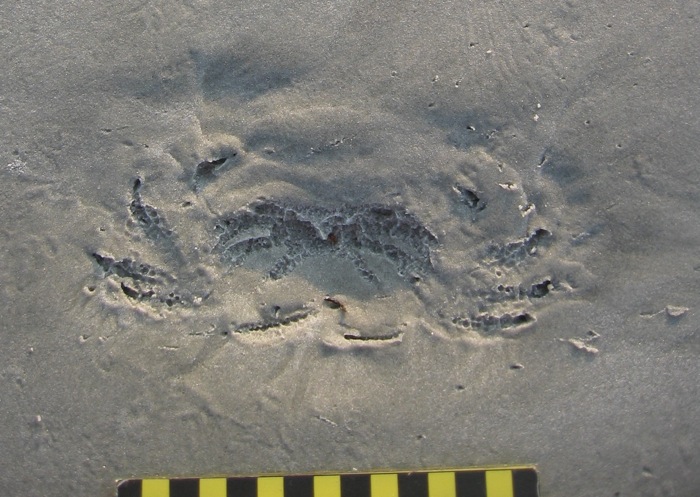

What is this long, meandering ridge making its way through a beach to the high tide mark on Sapelo Island, Georgia, and what made it? If you’re curious, please read on. But if you already know what it is, then you know a lot more than I did the first time I saw something like this. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

What is this long, meandering ridge making its way through a beach to the high tide mark on Sapelo Island, Georgia, and what made it? If you’re curious, please read on. But if you already know what it is, then you know a lot more than I did the first time I saw something like this. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

The last of those three scenarios happened to me on Sapelo Island, Georgia, in June 2004. My wife Ruth was with me, and we had just arrived on the island the previous afternoon, having stayed overnight at the University of Georgia (Athens) Marine Institute, or UGAMI. We decided that our first full morning in the field would be at Nannygoat Beach on the south end of Sapelo, which is a 5-minute drive or a 20-minute walk from the UGAMI.

We drove a field vehicle there (the gas gauge and everything else worked), parked, and took the boardwalk over the coastal dunes. Our elevated view from the boardwalk afforded a good look at many insect, ghost crab, bird, and mammal tracks made in the early morning. Circular holes punctured the dunes, made by ghost crabs (Ocypode quadrata). Sand aprons composed of still-moist sand were next to these burrow entrances, bearing crisply defined ghost-crab tracks, although early-morning sea breezes had already started to blur these.

At some point after walking onto the beach, though, we saw traces that we had not noticed in previous visits to Sapelo, and ones I have rarely seen there or on other Georgia barrier islands since. These oddities were meters-long, slightly sinuous to meandering ridges, about 15-20 cm (6-8 in) wide, extending in the sandy areas from the dunes through the berm and down to the high-tide mark, where they ended abruptly.

Same meandering ridge shown in the first photo, but viewed from the high-tide mark, showing how it connects with the primary dunes. Note how a few holes are punched in the part near me: more about those soon. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia. P.S.: My wife Ruth is the scale in both photos, fulfilling one of the top 10 signs that I might be a geologist.)

Same meandering ridge shown in the first photo, but viewed from the high-tide mark, showing how it connects with the primary dunes. Note how a few holes are punched in the part near me: more about those soon. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia. P.S.: My wife Ruth is the scale in both photos, fulfilling one of the top 10 signs that I might be a geologist.)

Although a few ridges crossed one another, they rarely branched, and if they did, the branches were quite short, only about 10-15 cm (4-6 in). When we followed them to the dunes, they seemed to originate from some unseen place below the sandy surfaces. We investigated further by cutting through some of the ridges to see what they looked like inside. They turned out to be mostly open tunnels with circular cross sections about 5 cm (2 in) wide, slightly wider than a U.S. dollar coin. They were mostly hollow, and only occasionally did we encounter a plug of sand interrupting tunnel interiors. This supposition was backed up by ridges that had collapsed into underlying voids. A few of the ridges stopped with a rounded end the same diameter as the ridge, or as a larger, raised, elliptically shaped “hill.”

Ridge with quite a bit of meander in it. Check out the short branch toward the top right, where the tracemaker must have changed its mind and backed up, then continued digging toward the viewer. Scale = 15 cm (6 in). (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

Ridge with quite a bit of meander in it. Check out the short branch toward the top right, where the tracemaker must have changed its mind and backed up, then continued digging toward the viewer. Scale = 15 cm (6 in). (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

Two separate ridges intersecting, caused by one crossing the other, resulting in “false branching.” Also notice the partial collapse of sand into underlying hollow tunnels and how one of the ridges ends in a rounded mound. Scale = 15 cm (6 in). (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

Two separate ridges intersecting, caused by one crossing the other, resulting in “false branching.” Also notice the partial collapse of sand into underlying hollow tunnels and how one of the ridges ends in a rounded mound. Scale = 15 cm (6 in). (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

A short ridge ending in a raised, elliptical “hill,” connected to a partially collapsed tunnel that is not otherwise evident as an elevated surface. Same scale as before. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

A short ridge ending in a raised, elliptical “hill,” connected to a partially collapsed tunnel that is not otherwise evident as an elevated surface. Same scale as before. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

Ruth and I agreed that these tunnels were burrows, instead of some random features made by the winds, tides, or waves. But by what? Clearly their makers were impressive burrowers, capable of digging through meters of sand. Their bodies also were probably just a little narrower than the burrow interiors, which helped us to think about body sizes. Then we considered where we were – dunes and beach – and what animals were the most likely ones to burrow in these environments.

A process of elimination – determining what they were not – was a good way to start figuring out their potential makers. For example, no way these burrows were from insects, such as beetle larvae, ant lion larvae, or mole crickets, because they were just too big. Insects also have a tough time handling salinity, so once they got to the surf zone with its saturated, saline sand, they would have had problems, or (more likely) an aversive reaction and turned around immediately instead of plowing ahead.

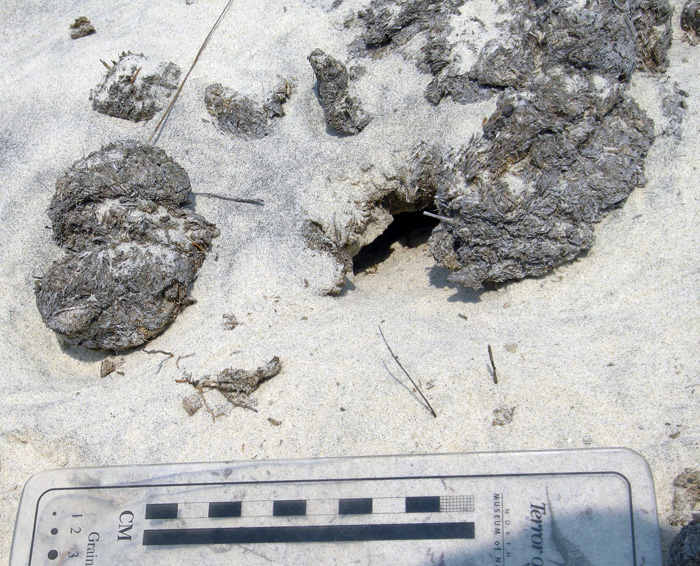

Insect burrow in coastal dune sand, made by a small beetle. Look at both the form and scale, and you’ll see this is not a match for what we were seeing. Scale in centimeters. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Cumberland Island, Georgia.)

Insect burrow in coastal dune sand, made by a small beetle. Look at both the form and scale, and you’ll see this is not a match for what we were seeing. Scale in centimeters. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Cumberland Island, Georgia.)

Small mammals, like beach mice (Peromyscus polionotus), didn’t seem like good candidates either. Beach-mouse burrows are totally different from what we were seeing, and their burrows do not run all of the way down to the intertidal zone. Mice, like insects, also don’t like marine-flavored water; even if they might be able to temporarily tolerate it, they wouldn’t continue to burrow through moist, salty sand.

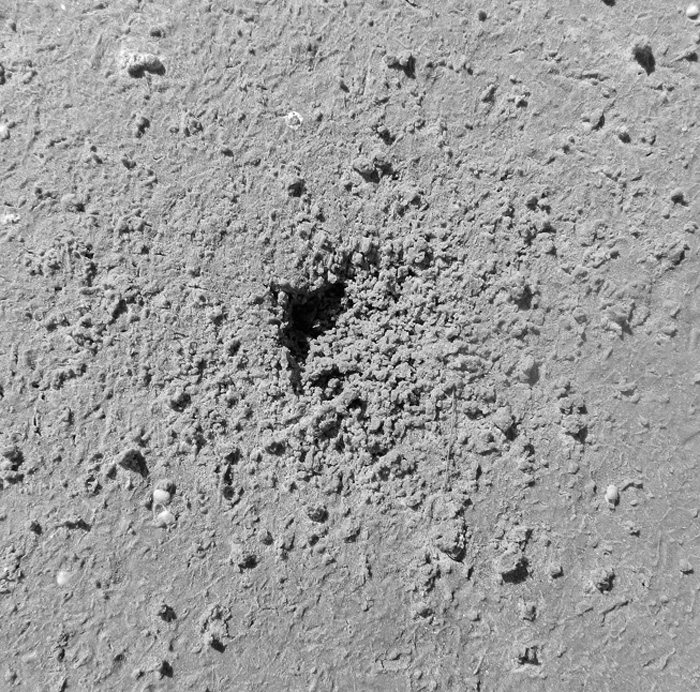

A beach-mouse burrow, with their tracks coming and going. Either the mice dug this burrow, or they occupied an abandoned ghost-crab burrow. Regardless, this also doesn’t match our mystery traces. Scale in millimeters. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Little St. Simons Island, Georgia.)

A beach-mouse burrow, with their tracks coming and going. Either the mice dug this burrow, or they occupied an abandoned ghost-crab burrow. Regardless, this also doesn’t match our mystery traces. Scale in millimeters. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Little St. Simons Island, Georgia.)

This led to an initial hypothesis that these burrows were from one of the most common larger burrowing animals in the area, and one comfortable in dune, berm, and beach environments with saturated, salty sand. These could only be from ghost crabs, I thought, an explanation supported by undoubted ghost crab burrows that perfectly intersected these tunnels, accompanied by undoubted ghost-crab tracks.

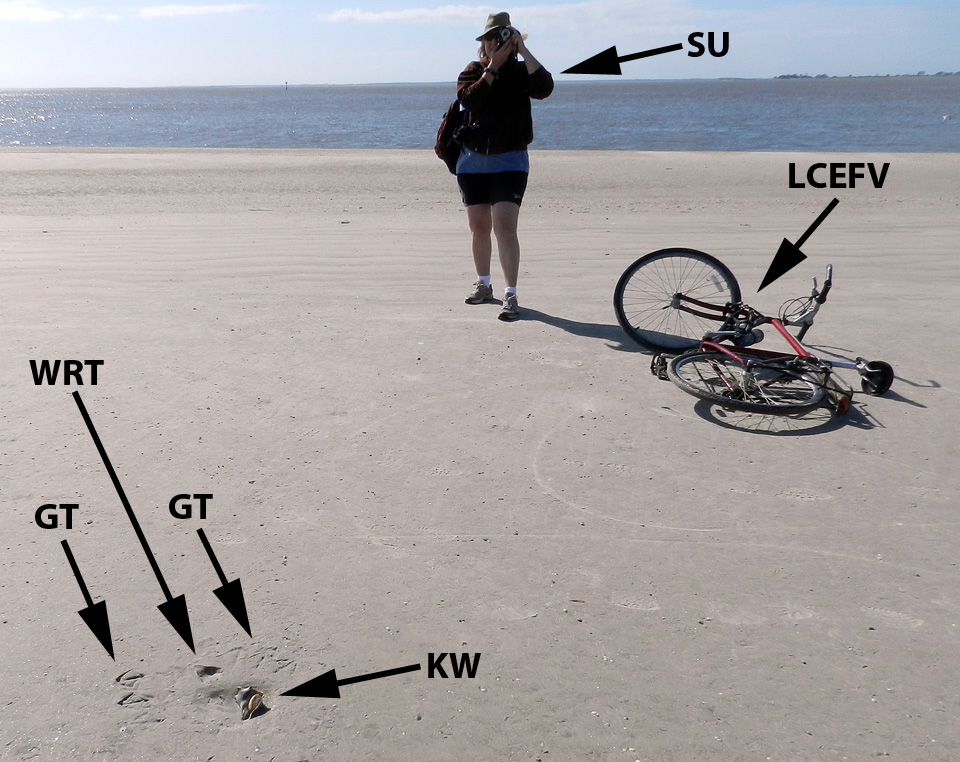

Ghost-crab burrows intersecting tunnels, accompanied by lots of ghost-crab tracks. Wow, that’s really convincing circumstantial evidence, wouldn’t you say? (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

Ghost-crab burrows intersecting tunnels, accompanied by lots of ghost-crab tracks. Wow, that’s really convincing circumstantial evidence, wouldn’t you say? (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

End of story, right? Well, no. I and a lot of other scientists have said this before, but it bears repeating: part of how science works is that in its practice we do not prove, we disprove. I somehow knew the “ghost crab burrowing horizontally through meters of sand from the dunes to the beach” hypothesis was a shaky one, and it bothered me that it just didn’t seem right. So I started reading as much as possible about ghost-crab burrowing behaviors. I thought I already knew a lot about this subject, but nonetheless was willing to acknowledge that there might be some holes in my learning (get it – holes?) that needed filling (get it – filling? Oh, never mind).

The gentle reader probably surmised what happened next. That’s right: not a single peer-reviewed reference mentioned ghost crabs digging meters-long shallow tunnels from the dunes to the beach. So either I was wrong, or I had documented a previously unknown and spectacular tracemaking behavior in this very well-studied species. A single cut by Occam’s Razor simply said, “You’re wrong.”

You thought I made long horizontal burrows that go all of the way from the dunes to the surf zone? Wow, you primates are dumber than I thought. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

You thought I made long horizontal burrows that go all of the way from the dunes to the surf zone? Wow, you primates are dumber than I thought. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

If not a ghost crab then, what else could make meters-long horizontal burrows of the diameter we had seen? This is when I began to reconsider my original rejection of moles as possible tracemakers.

So what am I: chopped liver? (Photograph from Kenneth Catania, Vanderbilt University, and taken from Wikipedia.org here.)

So what am I: chopped liver? (Photograph from Kenneth Catania, Vanderbilt University, and taken from Wikipedia.org here.)

Here’s what was the most interesting about this mistaken interpretation: it was made because of where we were. In other words, our initial mystification about these traces stemmed from their environmental context. Had we seen these burrows winding down a sandy road in the middle of a maritime forest on Sapelo Island, we would not have hesitated to say the word “mole.” Yet because we saw exactly the same types of burrows in coastal dunes and beaches, we said, “something else.”

A long, meandering mole burrow in the sandy road going through a maritime forest on the north end of Sapelo Island. So if you see a burrow like this in the forest, you instantly say “mole.” But if you see it on the beach, you say, “Um, uh, duh…must be something else!” My tracks (size 8 1/2, mens) and 15 cm (6 in) photo scale for, well, scale. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

A long, meandering mole burrow in the sandy road going through a maritime forest on the north end of Sapelo Island. So if you see a burrow like this in the forest, you instantly say “mole.” But if you see it on the beach, you say, “Um, uh, duh…must be something else!” My tracks (size 8 1/2, mens) and 15 cm (6 in) photo scale for, well, scale. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Another long, meandering ridge ended in a rounded “hill,” a trace that no one would hesitate to call a mole burrow, especially because it’s in the middle of a maritime forest. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

Another long, meandering ridge ended in a rounded “hill,” a trace that no one would hesitate to call a mole burrow, especially because it’s in the middle of a maritime forest. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

A trip back to the literature further confirmed the mole hypothesis while also serving up a big slice of humble pie. I was embarrassed to find that these same burrows were described and interpreted as mole burrows in an article published in 1986. Even more mortifying: my dissertation advisor (Robert “Bob” Frey) was the first author on the article; it had been published while I was doing my dissertation work with him; and I had read the article years ago, but didn’t remember the part about mole traces. It was like these burrows were saying to me, “Go back to school, young man.”

OK, so these are mole burrows. Case closed. Now that we’ve identified them, we can stop thinking about them, and go on to name something else. But that ain’t science either, is it? This one answer – mole burrows – actually inspires a lot of other questions about them, which could lead to heaps more science:

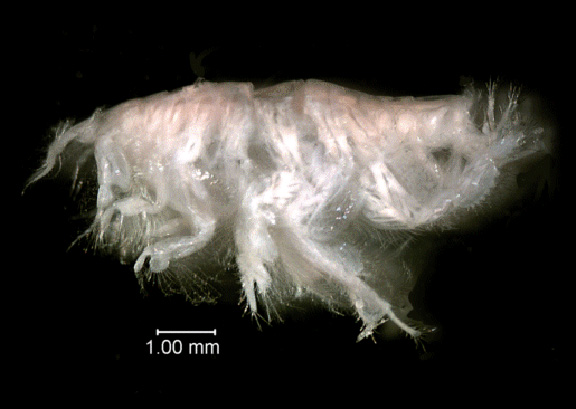

• Which moles made these burrows? The Georgia barrier islands have two documented species of moles, the eastern mole (Scalopus aquaticus) and star-nosed mole (Condylura cristata). Of these two, eastern moles are relatively common on island interiors, whereas star-nosed moles are either rare or locally extinct from some of the islands. But star-nosed moles are also more comfortable next to water bodies and seek underwater prey. So could these traces actually signal the presence of star-nosed moles in dune and beach environments? Frey and his co-author, George Pemberton, originally interpreted these as eastern mole burrows, but they also didn’t eliminate the possibility of star-nosed moles as the tracemakers, either.

• What is the evolutionary history of moles on the Georgia barrier islands? Are these moles descended from populations isolated from mainland ones 10,000 years ago by the post-Pleistocene sea-level rise, or do they represent more modern stock that somehow made its way to the islands? A genetic study would probably resolve this issue, but who the heck is going to compare the genetic relatedness of moles from the Georgia barrier islands to those on the mainland?

• What were they eating? Moles don’t just burrow for the exercise, but for the food. While burrowing, they are also voraciously chowing down on any invertebrate they encounter in the subsurface. But what would they eat in beach sands? As many shorebirds know, Georgia beaches are full of yummy amphipods, which would likely more than substitute for a mole’s typical earthworm– and insect-filled diet in terrestrial environments. Yet as far as I can find in the scientific literature, no one has documented mole stomach contents or scat from coastal environments to test whether these small crustaceans are their main prey or not.

• What happened to these moles once their burrows got to the surf zone? Did they turn around and burrow back, or did they go for a swim in the open ocean? The latter is actually not so far fetched, as moles are excellent swimmers, especially star-nosed moles. But how often would they do this?

• Just how common (or rare) are these burrows in beaches? Just because I just perceive these burrows as rare could be an example of sample bias. Yes, I wrote an entire book about Georgia-coast traces and tracemakers and have done field work on the islands since 1998. But I don’t live on the Georgia barrier islands, nor have I spent more than a week continuously on any of them. Keenly observant naturalists who live on the islands or otherwise spend much time there could better answer this question than me. I suspect they’re actually much more common than I originally supposed, and now look for them to photograph or otherwise document whenever I go back to any of the islands.

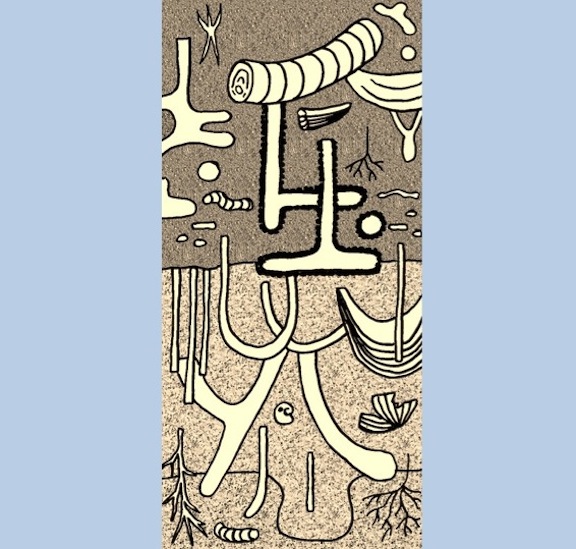

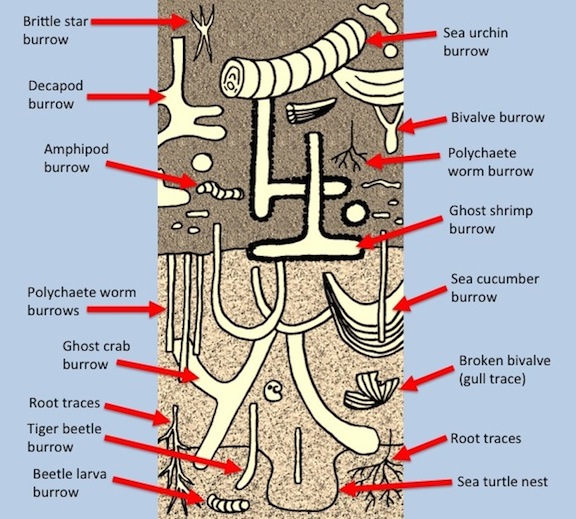

• Would such burrows preserve in the geologic record? Probably so, especially if they were made in dunes and filled with a differently colored or textured sand. But I’ll bet that nearly every paleontologist or geologist would make the same mistake I did, and reach for a burrowing marginal-marine crab or some other invertebrate as the tracemaker.

Geologists would be further fooled if fossil mole tunnels were intersected by genuine ghost-crab burrows, which would constitute a great example of a composite trace made by more than one species of animal. But why did the crabs burrow into the mole tunnels? Because it was easier. After all, the moles left hollow spaces and loosened sand over wide areas, practically begging ghost crabs to exploit these disturbed areas.

Anyway, I doubt many geologists would think of a small terrestrial mammal as a tracemaker for such burrows in sedimentary rocks formed in marginal-marine environments, although I’d love to be proved wrong on this. I’m hoping my writing about it here will help to prevent such confusion, and that whoever benefits from it will buy me an adult beverage as thanks.

In summary, this example of making a crab burrow out of a mole tunnel thus serves as a cautionary tale of how where we are when making observations in the field can influence our perceptions. But it also goes to show us how our wonderment with what we observe in natural environments can be renewed and encouraged by daring to be wrong once in a while, and learning from those mistakes.

Further Reading

Frey, R.W., and Pemberton, S.G. 1986. Vertebrate lebensspuren in intertidal and supratidal environments, Holocene barrier island, Georgia. Senckenbergiana Maritima, 18: 97-121.

Gorman, M.L., and Stone, R.D. 1990. The Natural History of Moles. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois: 138 p.

Harvey, M.J. 1976. Home range, movement, and diel activity of the eastern mole, Scalopus aquaticus. American Midland Naturalist, 95: 436-445.

Henderson, R.F. 1994. Moles. Prevention and Control of Wildlife Damage, Paper 49, University of Nebraska, Lincoln: D51-58. (Entire text here.)

Hickman, G.C. 1983. Influence of the semiaquatic habit in determining burrow structure of the star-nosed mole (Condylura cristata). Canadian Journal of Zoology, 61: 1688-1692.