At this time last year, Fernbank Museum of Natural History was hosting the Darwin exhibit. On loan from the American Museum of Natural History, this exhibit was a major coup for the museum and the Atlanta area, which has enjoyed a growing culture of celebrating science during the past few years. Along with this exhibit, the museum also planned and concurrently displayed an evolution-themed art show, appropriately titled Selections, which I wrote about then here.*

Descent with Modification (2011), mixed media (colored pencils and ink) on paper, 24″ X 36.” Although this artwork might at first look like a tentacled creature infested with crustaceans and living on a sea bottom, its main form actually mimics a typical burrow system made by ten-legged crustaceans (decapods). Yet it’s also an evolutionary hypothesis. Intrigued? If so, please read on. If not, there are plenty of funny cat-themed Web sites that otherwise require your attention. (Artwork and photograph of the artwork by Anthony Martin.)

Descent with Modification (2011), mixed media (colored pencils and ink) on paper, 24″ X 36.” Although this artwork might at first look like a tentacled creature infested with crustaceans and living on a sea bottom, its main form actually mimics a typical burrow system made by ten-legged crustaceans (decapods). Yet it’s also an evolutionary hypothesis. Intrigued? If so, please read on. If not, there are plenty of funny cat-themed Web sites that otherwise require your attention. (Artwork and photograph of the artwork by Anthony Martin.)

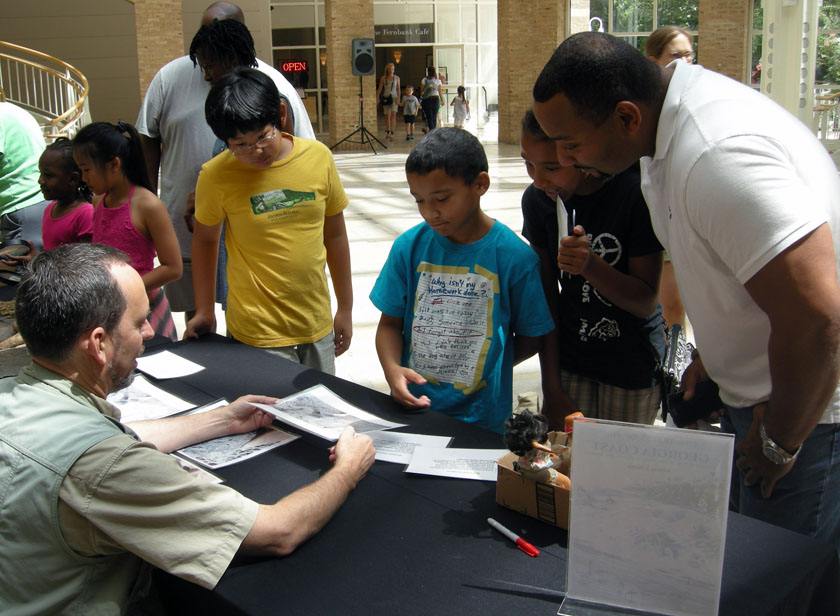

One unusual feature of this art show was that five of the eight artists were also scientists (full confession: I was one of them). Furthemore, one of the other artists was married to a scientist (fuller confession: that would be my wife Ruth). The show stayed up for more than three months, which was also as long as the Darwin exhibit resided at Fernbank. Thus we like to think it successfully exposed thousands of museum visitors to the concept that scientists, like many other humans, have artistic inspirations and abilities, neatly refuting the stereotype that not all of us are joyless, left-brained automatons and misanthropes.

Last week I was reminded of this anniversary and further connections between science and art during a campus visit last week by marine biologist and crustacean expert Joel Martin (no relation). Dr. Martin was invited to Emory University to give a public lecture with the provocative title God or Darwin? A Marine Biologist’s Take on the Compatibility of Faith and Evolution. His lecture was the first of several on campus this year about the intersections between matters of faith and science, the Nature of Knowledge Seminar Series. This series was organized as a direct response to the university inviting a commencement speaker this past May who held decidedly strong and publicly expressed anti-science views.

Dr. Martin, who is also an ordained elder in his Presbyterian church and has taught Sunday school to teenagers in his church for more than 20 years, gave an informative, organized, congenial, and otherwise well-delivered presentation to an audience of more than 200 students, staff, faculty, and other people from the Atlanta community. In his talk, Martin effectively explored the false “either-or” choice often presented to Americans who are challenged by those who unknowingly misunderstand or deliberately misrepresent evolutionary theory in favor of their beliefs. Much of what he mentioned, he said, is summarized in a book he wrote for teenagers and their parents, titled The Prism and the Rainbow: A Christian Explains Why Evolution is Not a Threat.

I purposefully won’t mention any of the labels that have been applied to the people and organizations who promote this divisiveness between evolutionary theory and faith. After all, words have power, especially when backed up by Internet search engines. Moreover, it is an old and tired subject, of which I grow weary discussing when there is so much more to learn from the natural world. Better to just say that Martin persuasively conveyed his personal wonder for the insights provided by evolutionary theory, how science informs and melds with his faith, and otherwise showed how science and faith are completely compatible with one another. You know, kind of like science and art.

Previous to his arrival, his host in the Department of Biology asked Emory science faculty via e-mail if any of us would like to have a one-on-one meeting with Dr. Martin during his time here. I leaped at the chance, and was lucky enough to secure a half-hour slot in his schedule. When he and I met in my office, we had an enjoyable chat on a wide range of topics, but mostly on our shared enthusiasm for the evolution of burrowing crustaceans, and particularly marine crustaceans.

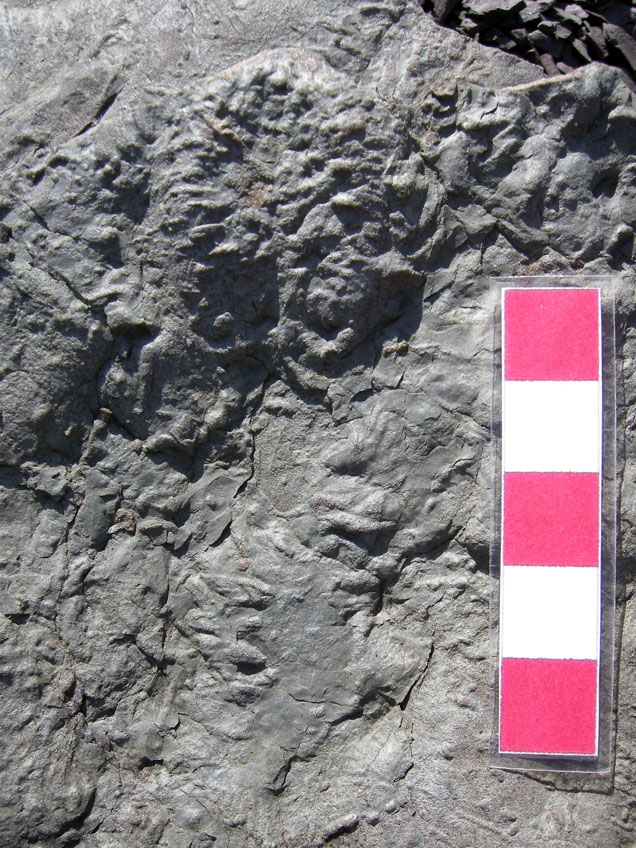

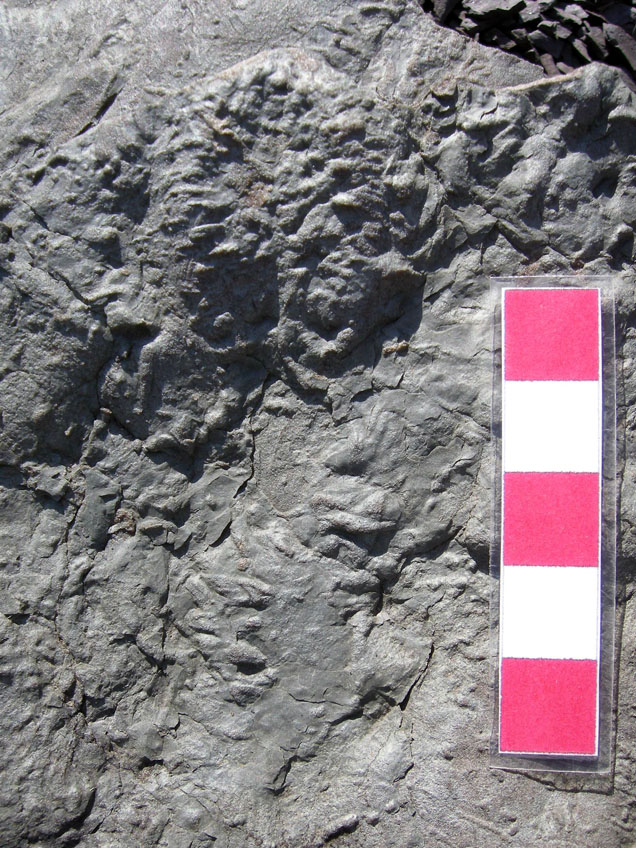

Ophiomorpha nodosa, a burrow network in a Pleistocene limestone of San Salvador, Bahamas. In this instance, the burrows were probably made by callianassid shrimp, otherwise known as “ghost shrimp,” and are preserved in what was a sandy patch next to a once-thriving reef from 125,000 years ago. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Ophiomorpha nodosa, a burrow network in a Pleistocene limestone of San Salvador, Bahamas. In this instance, the burrows were probably made by callianassid shrimp, otherwise known as “ghost shrimp,” and are preserved in what was a sandy patch next to a once-thriving reef from 125,000 years ago. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Interestingly, during this conversation we also touched on on how art and science work together, and I was pleasantly surprised to find out that Dr. Martin is a talented artist, too. It turns out he has illustrated many of his articles with exquisite line drawings of his beloved subjects, marine crustaceans. Yes, I realize that some artists like to draw a line (get it?) between being an “artist” and an “illustrator,” with the latter being held in some sort of disdain for merely “copying” what is seen in nature. If you’re one of those, sorry, I don’t have the time or inclination to argue about this with you. (Now go back to putting a red dot on a white canvas and leave us alone.)

Cover art of branchiopod Lepidurus packardi from California, drawn by Joel W. Martin, for An Updated Classification of the Recent Crustacea, also co-authored by Joel W. Martin and George E. Davis: No. 39, Science Series, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, California.

Cover art of branchiopod Lepidurus packardi from California, drawn by Joel W. Martin, for An Updated Classification of the Recent Crustacea, also co-authored by Joel W. Martin and George E. Davis: No. 39, Science Series, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, California.

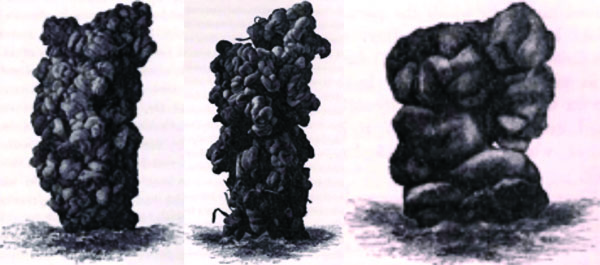

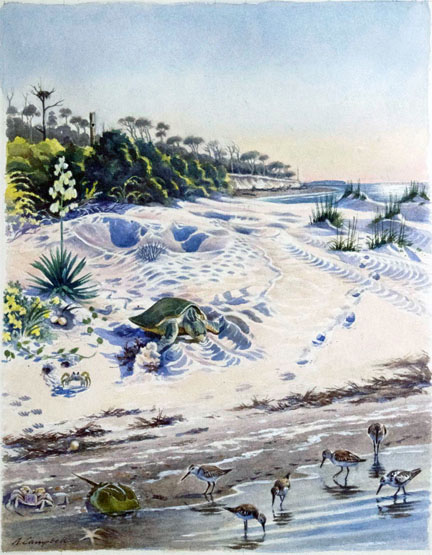

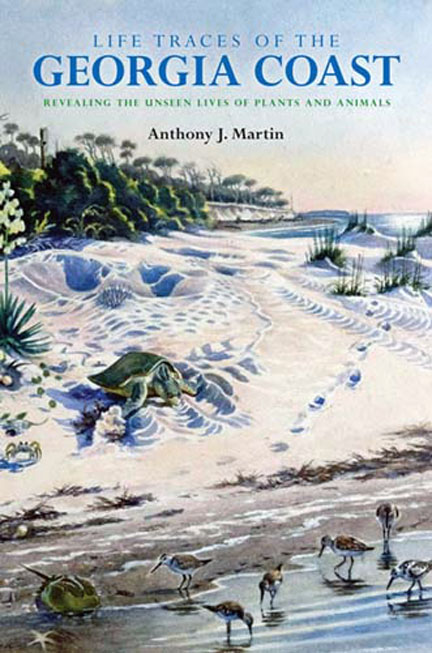

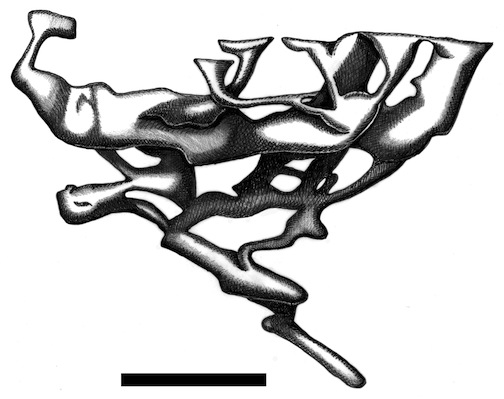

During our discussion in my office, I pointed out a enlarged reproduction of a drawing of mine depicting the burrow complex of an Atlantic mud crab (Panopeus herbstii). He immediately recognized it as a crustacean burrow, for which I was glad, because it is an illustration of just that in my upcoming book, Life Traces of the Georgia Coast.

Burrow complex made by Atlantic mud crab (Panopeus herbstii), originally credited to a snapping shrimp (Alpheus heterochaelis). Scale = 5 cm (2 in). (Illustration by Anthony Martin, based on epoxy resin cast figured by Basan and Frey (1977).

Burrow complex made by Atlantic mud crab (Panopeus herbstii), originally credited to a snapping shrimp (Alpheus heterochaelis). Scale = 5 cm (2 in). (Illustration by Anthony Martin, based on epoxy resin cast figured by Basan and Frey (1977).

After his campus visit, though, I realized that an even more appropriate artistic work to have shown him was the following one made for the Selections art exhibit last fall, titled Descent with Modification. This title in honor of the phrase used by Charles Darwin to describe the evolutionary process, but also is a play on words connecting to the evolution of burrowing crustaceans.

Descent with Modification again, but this time look at it as an evolutionary chart, where the burrow junctions in the burrow system reflect divergence points (nodes) from common ancestors. For example, from left to right, the ghost shrimp is more closely related to a mud shrimp, and both of these are more closely related to the ghost crab (middle) than they are to the lobster and freshwater crayfish (right). The main vertical burrow shaft represents their common ancestry from a “first decapod,” which may have been as far back as the Ordovician Period, about 450 million years ago.

Descent with Modification again, but this time look at it as an evolutionary chart, where the burrow junctions in the burrow system reflect divergence points (nodes) from common ancestors. For example, from left to right, the ghost shrimp is more closely related to a mud shrimp, and both of these are more closely related to the ghost crab (middle) than they are to the lobster and freshwater crayfish (right). The main vertical burrow shaft represents their common ancestry from a “first decapod,” which may have been as far back as the Ordovician Period, about 450 million years ago.

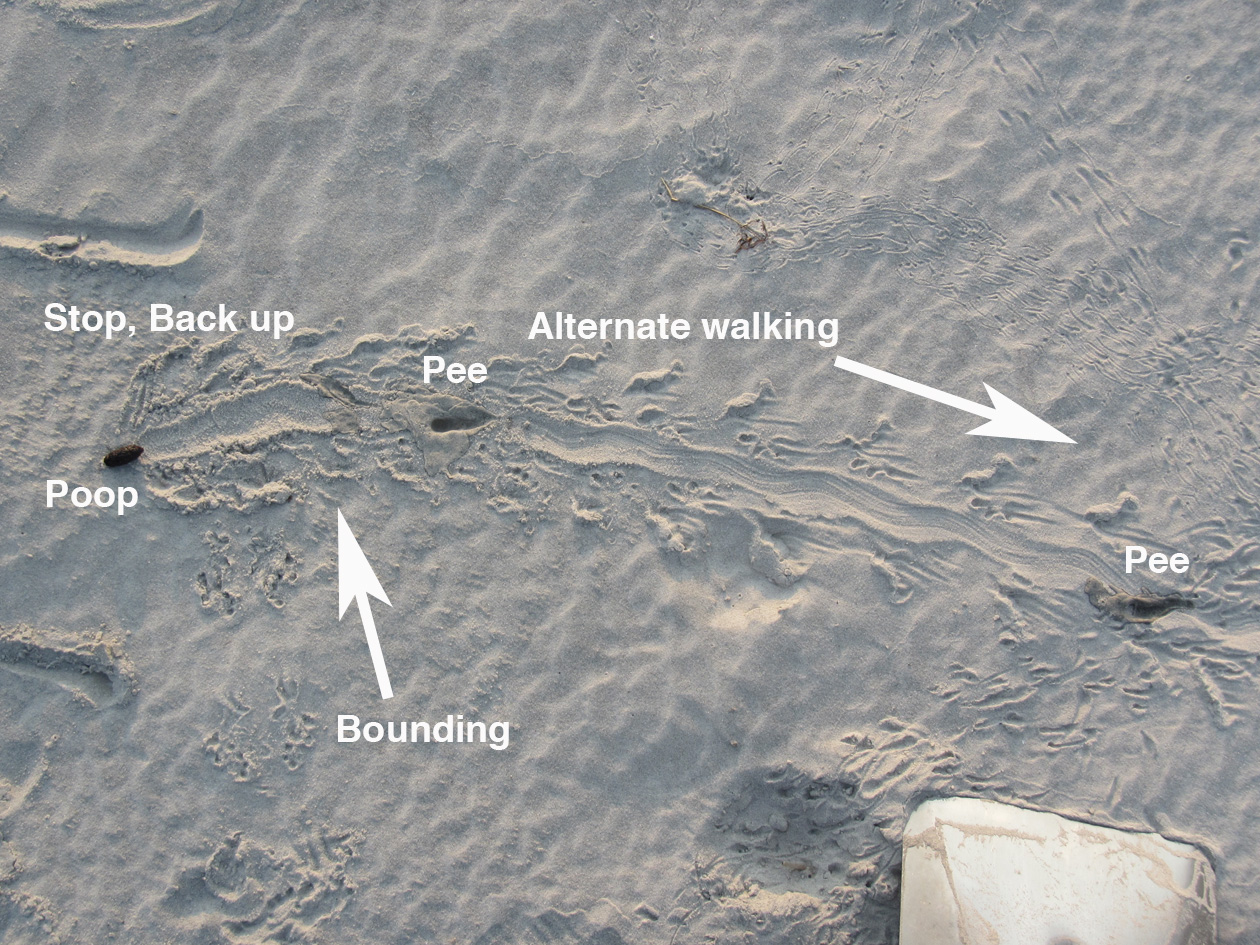

The image shows five burrowing crustaceans, or to be more specific, ten-legged crustaceans called decapods. Along with these is a structure, which has a burrow entrance surrounded by a conical mound of excavated and pelleted sediment, a vertical shaft connecting to the main burrow network, and branching tunnels that lead to terminal chambers. A burrowing crustacean occupies each chamber, and these are, from left to right: a ghost shrimp (Callichirus major), a mud shrimp (Upogebia pusilla), a ghost crab (Ocypode quadrata), a marine lobster (Homarus gammarus), and a freshwater crayfish (Procambarus clarkii).

Here’s the cool part (or at least I think so): this burrow system also serves as an evolutionary chart – kind of a cladogram – depicting the ancestral relationships of these modern burrowing decapods. For example, lobsters and crayfish are more closely related to one another (share a more recent common ancestor) than lobsters are related to crabs. Mud shrimp are more closely related to crabs than ghost shrimp. Accordingly, the burrow junctions show where these decapod lineages diverged. So the title of the artwork is a double entendre with reference to Darwin’s phrase describing evolution as a process of “descent with modification,” along with burrowing decapods undergoing change through time as they descend in the sediment.

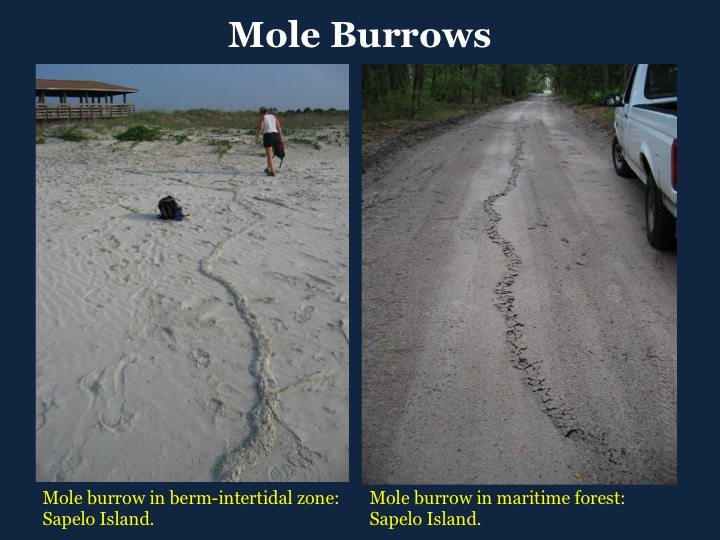

Modern decapod burrows and trace fossils of probable decapod burrows support both the science and the artwork, too. Here are a few examples to whet your ichnological and aesthetic appetites:

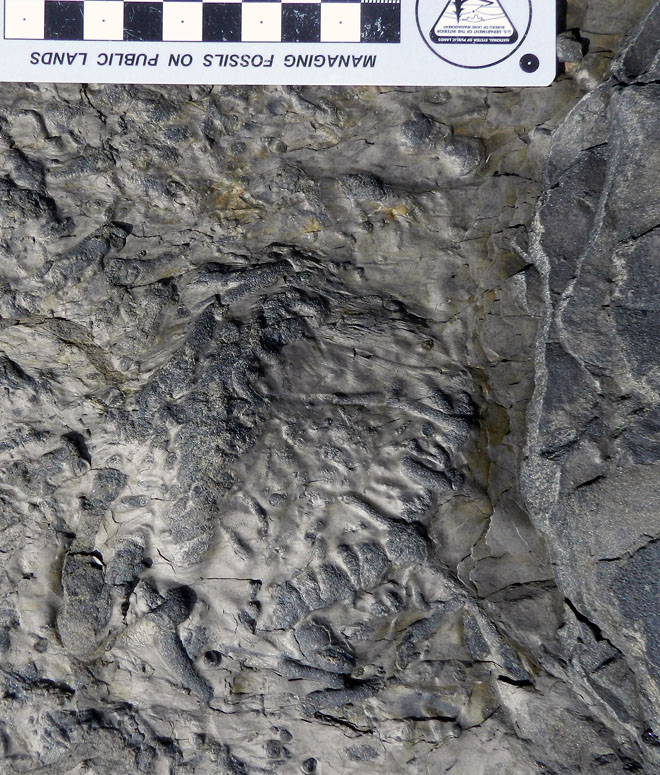

Thalassinoides, a trace fossil of horizontally oriented and branching burrow systems made by decapods in Early Cretaceous rocks (about 115 mya) of Victoria, Australia. In this case, these burrows were likely by freshwater decapods, such as crayfish, which had probably diverged from a common ancestor with marine lobsters more than 100 million years before then. Scale = 10 cm (4 in). (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Thalassinoides, a trace fossil of horizontally oriented and branching burrow systems made by decapods in Early Cretaceous rocks (about 115 mya) of Victoria, Australia. In this case, these burrows were likely by freshwater decapods, such as crayfish, which had probably diverged from a common ancestor with marine lobsters more than 100 million years before then. Scale = 10 cm (4 in). (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Thalassinoides again, but this time in limestones formed originally in marine environments, from the Miocene of Argentina. Note the convergence in forms of the burrows with those of the freshwater crayfish ones in Australia. Think that might be related to some sort of evolutionary heritage? Scale = 15 cm (6 in). (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Thalassinoides again, but this time in limestones formed originally in marine environments, from the Miocene of Argentina. Note the convergence in forms of the burrows with those of the freshwater crayfish ones in Australia. Think that might be related to some sort of evolutionary heritage? Scale = 15 cm (6 in). (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Horizontally oriented burrow junction of a modern ghost shrimp – probably made by a Carolina ghost shrimp (Callichirus major) – exposed along the shoreline of Sapelo Island, Georgia. Note the pelleted exterior, which is also visible on the burrow networks of the fossil ones in the Bahamas, pictured earlier. So if fossilized, this would be classified as the trace fossil Ophiomorpha nodosa. Scale in centimeters. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Horizontally oriented burrow junction of a modern ghost shrimp – probably made by a Carolina ghost shrimp (Callichirus major) – exposed along the shoreline of Sapelo Island, Georgia. Note the pelleted exterior, which is also visible on the burrow networks of the fossil ones in the Bahamas, pictured earlier. So if fossilized, this would be classified as the trace fossil Ophiomorpha nodosa. Scale in centimeters. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Two ghost-shrimp burrow entrances on a beach of Sapelo Island, Georgia, with the one on the right showing evidence of its occupant expelling water from its burrow. No scale, but burrow mound on right is about 5 cm (2 in) wide. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Two ghost-shrimp burrow entrances on a beach of Sapelo Island, Georgia, with the one on the right showing evidence of its occupant expelling water from its burrow. No scale, but burrow mound on right is about 5 cm (2 in) wide. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Burrow entrance and conical, pelleted mound made by a freshwater crayfish (probably a species of Procambarus) in the interior of Jekyll Island, Georgia. Scale = 1 cm (0.4 in). (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Burrow entrance and conical, pelleted mound made by a freshwater crayfish (probably a species of Procambarus) in the interior of Jekyll Island, Georgia. Scale = 1 cm (0.4 in). (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

So the take-away message of all of these musings and visual depictions is that evolution, faith, science, art, trace fossils, modern burrows, and burrowing decapods can all co-exist and be celebrated, regardless of whether we sing Kumbaya or not. So let’s stop dividing one another, get out there, and learn.

*I’m also proud to say that my post from October 17, 2011, Georgia Life Traces as Art and Science, was nominated for possible inclusion in Open Laboratory 2013. Thank you!

Further Reading

Basan, P.B., and Frey, R.W. 1977. Actual-palaeontology and neoichnology of salt marshes near Sapelo Island, Georgia. In Crimes, T.P., and Harper, J.C. (editors), Trace Fossils 2. Liverpool, Seel House Press: 41-70.

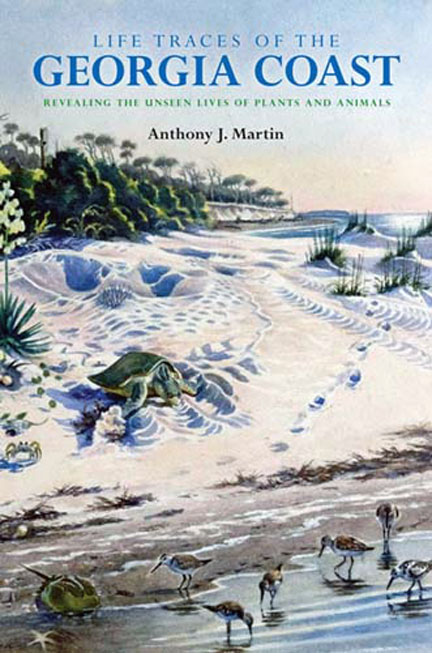

Martin, A.J. In press. Life Traces of the Georgia Coast: Revealing the Unseen Lives of Plants and Animals. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN: 680 p.

Martin, A.J., Rich, T.H., Poore, G.C.B., Schultz, M.B., Austin, C.M., Kool, L., and Vickers-Rich, P. 2008. Fossil evidence from Australia for oldest known freshwater crayfish in Gondwana. Gondwana Research, 14: 287-296.

Martin, J.W. 2010. The Prism and the Rainbow: A Christian Explains Why Evolution is Not a Threat. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD: 192 p.

Martin, J.W., and Davis. G.E. 2001. An Updated Classification of the Recent Crustacea, No. 39, Science Series, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, California: 132 p.