Every time I travel away from home, I make a point of looking at the ground. The main reason for this seemingly odd behavior is to make sure I detect traces of whoever else might be living in my temporary neighborhood. This ichnological practice came in handy last month while I was doing field work in the high plains of central Montana. Located just east of the front range of the Rocky Mountains, this area – which happens to have some lovely Late Cretaceous trace fossils – is also prime real estate for grizzly bears.

Had we found this in the woods, it would have answered just one specific question. But because it was in the high plains of Montana, it generated a lot more questions than answers. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in central Montana.)

Had we found this in the woods, it would have answered just one specific question. But because it was in the high plains of Montana, it generated a lot more questions than answers. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in central Montana.)

Grizzly bears (Ursus arctos) are the largest land carnivores in North America. The earliest written records describing grizzly bears came from Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who traipsed through this part of Montana with their expedition in the early 19th century. After several encounters, they soon verified that this species was much tougher than they had presupposed, often taking more than ten shots from then-modern rifles to kill. To make matters worse, it had a low tolerance for upright bipeds traipsing, skipping, sashaying, or dosey-doeing in its territory. Moreover, these bears possessed the means to enforce their you-no-go-here zones. There’s something about weighing 300+ kg (700+ lbs), having powerful limbs ending in huge claws, big teeth, an ability to run more than 50 kph (30+ mph), and an aggressive attitude that persuasively argued for people to avoid them whenever possible.

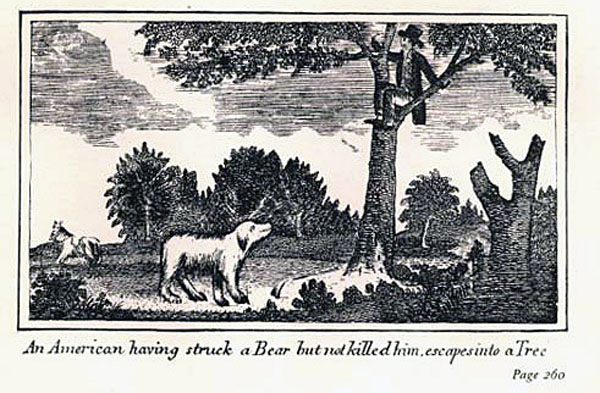

Lewis and Clark thought they were badasses because they carried boom sticks, but Mr. Chocolate soon showed them why grizzlies were the Mongos of the animal kingdom: shooting them sometimes got them mad. (Image is originally from Sargent Patrick Gass’s journal and borrowed from Frances Hunter’s American Heroes Blog, co-written by Mary and Liz Clare.)

Lewis and Clark thought they were badasses because they carried boom sticks, but Mr. Chocolate soon showed them why grizzlies were the Mongos of the animal kingdom: shooting them sometimes got them mad. (Image is originally from Sargent Patrick Gass’s journal and borrowed from Frances Hunter’s American Heroes Blog, co-written by Mary and Liz Clare.)

So although the area where I did field work in Montana is world famous for its dinosaur nests and other fossil evidence, modern grizzly-bear traces there also mean I associate this place with these animals. For instance, I’ll never forget my first morning there in 2000, when – while walking to an outcrop I’d be studying by myself for the next six days – I encountered fresh grizzly tracks in one of the arroyos. These traces readily explained why I heard a pack of coyotes making a racket the night before, while also invoking mild anxiety in this petite paleontologist once I realized the surrounding environment lacked any trees or other means of escaping an angry grizzly.

Left rear-foot track of an adult grizzly bear, left in the muddy sand of an arroyo next to a Cretaceous outcrop where I did field work in 2000. Notice the length of its claws, which left marks well in front of its toes. Photo was taken about four days after I had seen them freshly made my first day in this area of Montana. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Left rear-foot track of an adult grizzly bear, left in the muddy sand of an arroyo next to a Cretaceous outcrop where I did field work in 2000. Notice the length of its claws, which left marks well in front of its toes. Photo was taken about four days after I had seen them freshly made my first day in this area of Montana. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

This time, with 14 more years of tracking experience behind me, I felt a little more confident about detecting grizzly-bear tracks and other sign, and looked forward to seeing these traces, but not their tracemakers. Thus I was pleased when my field companions and I found several-weeks-old evidence of a grizzly during my first morning there. Yet these traces were not tracks. Instead, they consisted of scat bearing (sorry) some never-before-seen items (for me, anyway), accompanied by nearby feeding signs that directly connected to another trace made by another animal.

So let’s first talk feces. Based on its size alone, we quickly determined that this deposit was from a grizzly bear, as the two pieces collectively were about 15 cm (6 in) long and about 5 cm (2 in) wide. Nearby coyote scat nearby gave some perspective: although 20 cm (8 in) long, it was only 2 cm (0.8 in) wide, indicating a much smaller anal diameter. However, that wasn’t the largest grizzly scat I’d ever seen, which made us think that maybe it was from a young bear.

But was really puzzled us was the contents of the scat: it was full of ants and grass stems. Despite none of us being entomologists, let alone myrmecologists, we recognized the red-and-black ant parts in the scat were from an ant common there in the high plains, and probably some species of Formica. Colonies of this ant built nests with prominent domes at the ground surface, which are composed of a mixture of soil and grass stems. Hmm, ants and grass stems: what could it mean?

See all of those orange and black bits in this scat? Those are ant parts that passed through the digestive tract of a grizzly bear. Notice these pieces are accompanied by lots of plant fibers, which must have provided some healthy roughage. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in central Montana.)

See all of those orange and black bits in this scat? Those are ant parts that passed through the digestive tract of a grizzly bear. Notice these pieces are accompanied by lots of plant fibers, which must have provided some healthy roughage. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in central Montana.)

OK, you already got it: this scat was evidence of a grizzly bear that ate ants. But the grass also showed that this grizzly ingested a lot of plant debris along with these yummy insects. This implied that it must have been chowing down on the top of an ant nest, scooping up insects and grass stems indiscriminately, like it was dining on an ant salad. Furthermore, knowing how ants tend to defend attacks on their nests, they probably swarmed upward in great numbers and straight into this grizzly bear’s mouth, unwittingly aiding its efforts. (Incidentally, an insectivorous member of our field crew had been tasting these ants just minutes before we found the scat and independently confirmed their delectable qualities.)

Ant-nest mound in the field area composed mostly of grass stems, and probably made by a species of Formica. Scale is a size 8 1/2 (men’s) boot. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Ant-nest mound in the field area composed mostly of grass stems, and probably made by a species of Formica. Scale is a size 8 1/2 (men’s) boot. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Close-up of the ants in the colony moving in and out of a nest entrance, in between all of the grass stems. Also, check out those black abdomens and reddish-orange thoraxes and heads, which we now know don’t change color much after spending time inside a grizzly bear. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in central Montana.)

Close-up of the ants in the colony moving in and out of a nest entrance, in between all of the grass stems. Also, check out those black abdomens and reddish-orange thoraxes and heads, which we now know don’t change color much after spending time inside a grizzly bear. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in central Montana.)

So how did we know that the grizzly was “scooping” (using its paws) instead of simply mashing its face into the nest like it was competing in an ant-eating contest at a grizzly-bear fair? Ah, that was the other trace evidence. Only a couple of meters away from the scat were two big pits. These pits showed exactly where the ant-eating grizzly had used its big-clawed paws to rip into a couple of nests. While taking into consideration the needed residence time of ants in a grizzly gut, we figured this bear had already raided a nest somewhere else and pooped here, or it came back to this place for seconds the next day. Either way, it left a little calling card for us bipeds and any other mammals in the area, warning us to stay away from its ant stash.

Ever wonder what a grizzly-bear-ant-eating pit looks like? Wonder no more, here’s two of them. The one on the left was about a meter (3.3 ft) across, whereas the one on the right was closer to 1.5 m (5 ft) wide. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Ever wonder what a grizzly-bear-ant-eating pit looks like? Wonder no more, here’s two of them. The one on the left was about a meter (3.3 ft) across, whereas the one on the right was closer to 1.5 m (5 ft) wide. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

What was very gratifying about these traces is how they reflected the same sort of insectivorous bear behaviors I had discerned in black-bear traces in forests of Wyoming and Idaho. The big difference, though, was in the types of insects and substrates. Insect-eating bears in forests rip open rotten logs for their fodder, which mostly would hold wood-eating beetle grubs; this behavior leaves huge gouges and scatters wood chips around the feeding site. Without trees, the same behavior means digging into the soil, and after different insects, such as moths and ants, and the traces will be large pits like the ones we saw.

So how would traces like these look in the fossil record? Better yet, how would our knowledge of these grizzly-bear traces help us to test whether any dinosaurs did similar behaviors, such as tearing into Mesozoic ant or termite nests and feasting on these little protein-rich treats?

Well, you’re lucky that I’m the person asking such rhetorical questions, because I just happened to have talked about about this in my most recent book, Dinosaurs Without Bones. Based on their anatomies, dinosaurs accused of ant- or termite-eating behaviors include a few unusual theropods, such as alvarezasaurs and therizinosaurs. Very simply, dinosaur trace fossils of insectivory would be analogous to what we saw with these grizzly-bear traces in Montana. Lacking dinosaur skeletons with insect parts in its gut region, trace fossils might include coprolites containing abundant ant parts, accompanied by sediments or plant debris from their nests. Even better would be a fossil ant or termite nest with visible damage matching the claws or other body parts of these suspected dinosaurs.

Have paleontologists ever found such two-for-one ichnological specials? Not yet, but given an awareness of modern insect-eating animals and the traces – some of which are next to Mesozoic rocks – I have every confidence that we’ll discover find them some day.