American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis) tend to provoke strong feelings in people, but the one I encounter the most often is awe, followed closely by fear. Both emotions are certainly justifiable, considering how alligators are not only the largest reptiles living on the Georgia barrier islands, but also are the top predators in both freshwater and salt-water ecosystems in and around those islands. I’ve even encountered them often enough in maritime forests of the islands to regard them as imposing predators in those ecosystems, too.

Time for a relaxing stroll through the maritime forest to revel in its majestic live oaks, languid Spanish moss, and ever-so-green saw palmettos. Say, does that log over there look a little odd to you? (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island.)

Time for a relaxing stroll through the maritime forest to revel in its majestic live oaks, languid Spanish moss, and ever-so-green saw palmettos. Say, does that log over there look a little odd to you? (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island.)

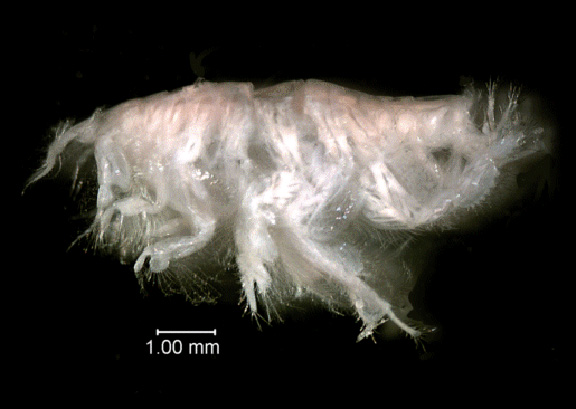

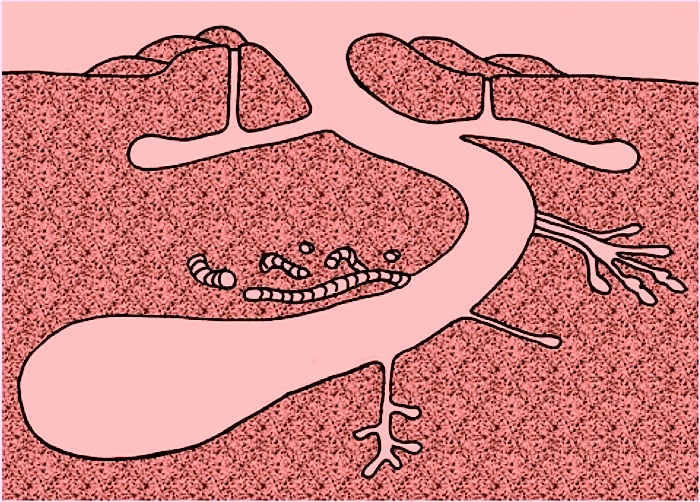

But what many people may not know about these Georgia alligators is that they burrow. I’m still a little murky on exactly how they burrow, but they do, and the tunnels of alligators, large and small, are woven throughout the interiors of many Georgia barrier islands. Earlier this week, I was on one of those islands – St. Catherines – having started a survey of alligator burrow locations, sizes, and ecological settings.

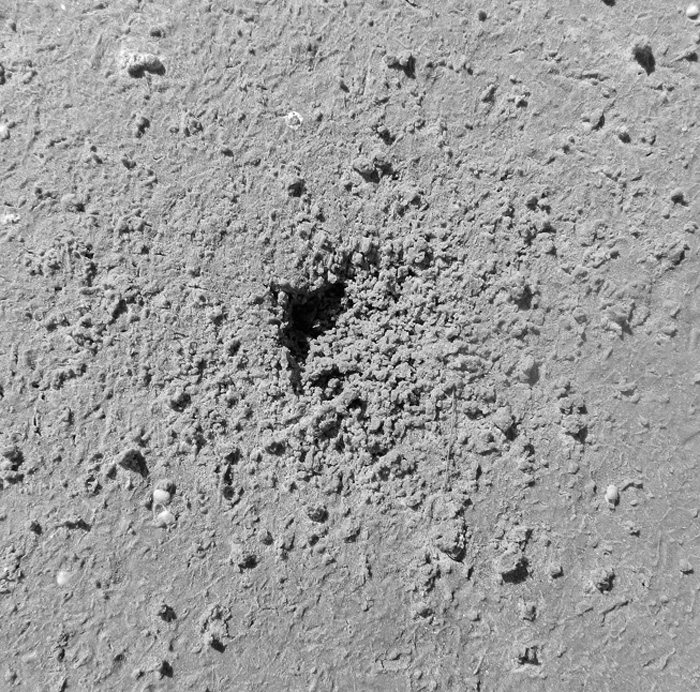

Entrance to an alligator burrow in a former freshwater marsh, now dry, yet the burrow is filled with water. How did water get into the burrow, and how does such traces help alligators to survive and thrive? Please read on. (Photograph by Anthony Martin and taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Entrance to an alligator burrow in a former freshwater marsh, now dry, yet the burrow is filled with water. How did water get into the burrow, and how does such traces help alligators to survive and thrive? Please read on. (Photograph by Anthony Martin and taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

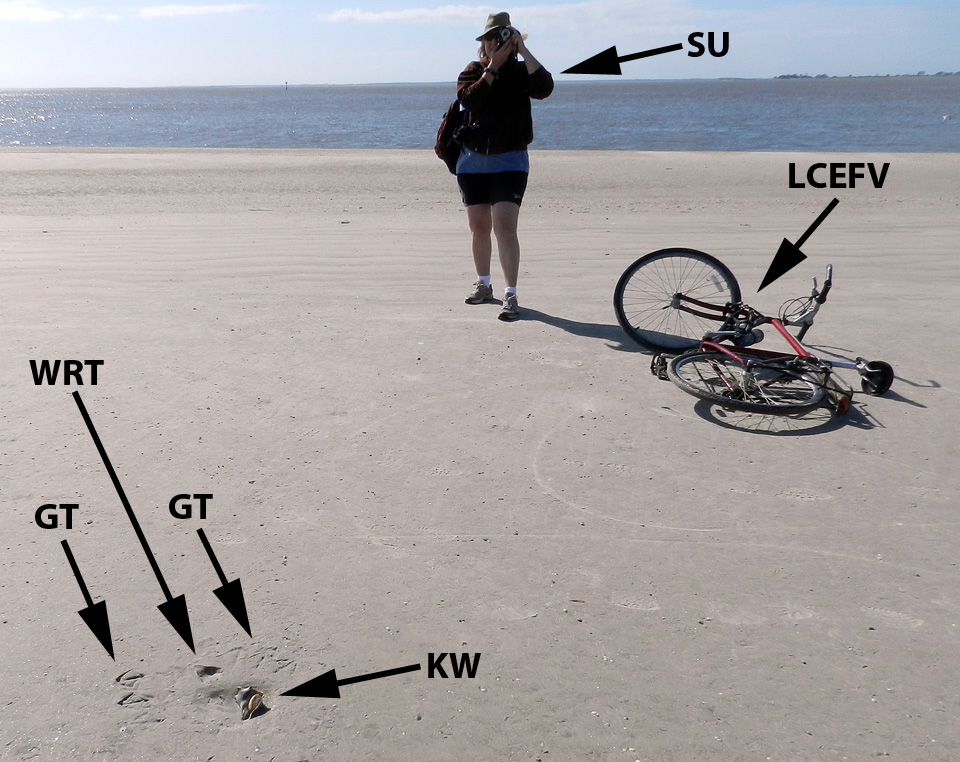

In this project, I’m working cooperatively (as opposed to antagonistically) with a colleague of mine at Emory University, Michael Page, as well as Sheldon Skaggs and Robert (Kelly) Vance of Georgia Southern University. As loyal readers may recall, Sheldon and Kelly worked with me on a study of gopher tortoise burrows, also done on St. Catherines Island, in which we combined field descriptions of the burrows with imaging provided by ground-penetrating radar (also known by its acronym, GPR). Hence this project represents “Phase 2” in our study of large reptile burrows there, which we expect will result in at least two peer-reviewed papers and several presentations at professional meetings later this year.

Why is a paleontologist (that would be me) looking at alligator burrows? Well, I’m very interested in how these modern burrows might help us to recognize and properly interpret similar fossil burrows. Considering that alligators and tortoises have lineages that stretch back into the Mesozoic Era, it’s exciting to think that through observations we make of their descendants, we could be witnessing evolutionary echoes of those legacies today.

Indeed, for many people, alligators evoke thoughts of those most famous of Mesozoic denizens – dinosaurs – an allusion that is not so farfetched, and not just because alligators are huge, scaly, and carnivorous. Alligators are also crocodilians, and crocodilians and dinosaurs (including birds) are archosaurs, having shared a common ancestor early in the Mesozoic. However, alligators are an evolutionarily distinct group of crocodilians that likely split from other crocodilians in the Late Jurassic or Early Cretaceous Period, an interpretation based on both fossils and calculated rates of molecular change in their lineages.

Archosaur relatives, reunited on the Georgia coast: great egrets (Ardea alba), which are modern dinosaurs, nesting above American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis), which only remind us of dinosaurs, but shared a common ancestor with them in the Mesozoic Era. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Archosaur relatives, reunited on the Georgia coast: great egrets (Ardea alba), which are modern dinosaurs, nesting above American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis), which only remind us of dinosaurs, but shared a common ancestor with them in the Mesozoic Era. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Along these lines, I was a coauthor on a paper that documented the only known burrowing dinosaur – Oryctodromeus cubicularis – from mid-Cretaceous rocks in Montana. In this discovery, we had bones of an adult and two half-grown juveniles in a burrow-like structure that matched the size of the adult. I also interpreted similar structures in Cretaceous rocks of Victoria, Australia as the oldest known dinosaur burrows. Sadly, these structures contained no bones, which of course make their interpretation as trace fossils more contentious. Nonetheless, I otherwise pointed out why such burrows would have been likely for small dinosaurs, especially in Australia, which was near the South Pole during the Cretaceous. At least a few of these reasons I gave in the published paper about these structures were inspired by what was known about alligator burrows.

Natural sandstone cast of the burrow of the small ornithopod dinosaur, Oryctodromeus cubicularis, found in Late Cretaceous rocks of western Montana; scale = 15 cm (6 in). (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Montana, USA.)

Natural sandstone cast of the burrow of the small ornithopod dinosaur, Oryctodromeus cubicularis, found in Late Cretaceous rocks of western Montana; scale = 15 cm (6 in). (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Montana, USA.)

Enigmatic structure in Early Cretaceous rocks of Victoria, Australia, interpreted as a small dinosaur burrow. It was nearly identical in size (about 2 meters long) and form (gently dipping and spiraling tunnel) to the Montana dinosaur burrow. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Victoria, Australia.)

Enigmatic structure in Early Cretaceous rocks of Victoria, Australia, interpreted as a small dinosaur burrow. It was nearly identical in size (about 2 meters long) and form (gently dipping and spiraling tunnel) to the Montana dinosaur burrow. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken in Victoria, Australia.)

What are the purposes of modern alligator burrows? Here are four to think about:

• Dens for Raising Young Alligators – Many of these burrows, like the burrow interpreted for the dinosaur Oryctodromeus, serve as dens for raising young. In such instances, these burrows are occupied by big momma ‘gators, who use them for keeping their newly hatched (and potentially vulnerable) offspring safe from other predators.

Two days ago, Michael and I experienced this behavioral trait in a memorable way while we documented burrow locations. As we walked along the edge of an old canal cutting through the forest, baby alligators, alarmed by our presence, began emitting high-pitched grunts. This then provoked a large alligator – their presumed mother – to enter the water. Her reaction effectively discouraged us from approaching the babies; indeed, we promptly increased our distance from them. (Our mommas didn’t raise no dumb kids.) So although we were hampered in finding out the exact location of this mother’s den, it was likely very close to where we first heard the grunting babies. I have also seen mother alligators on St. Catherines Island usher their little ones through a submerged den entrance, quickly followed by the mother turning around in the burrow and standing guard at the front door.

Oh, what an adorable little baby alligator! What’s that? You say your mother is a little over-protective? Oh. I see. I think I’ll be leaving now… (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island.)

Oh, what an adorable little baby alligator! What’s that? You say your mother is a little over-protective? Oh. I see. I think I’ll be leaving now… (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island.)

• Temperature Regulation – Sometimes large male alligators live by themselves in these burrows, like some sort of saurian bachelor pad. For male alligators on their own, these structures are important for maintaining equitable temperatures for these animals. Alligators, like other poikilothermic (“cold-blooded”) vertebrates, depend on their surrounding environments for controlling their body temperatures. Even south Georgia undergoes freezing conditions during the winter, and of course summers there can get brutally hot. Burrows neatly solve both problems, as these “indoor” environments, like caves, provide comfortable year-round living in a space that is neither too cold nor too hot, but just right. The burrowing ability of alligators thus makes them better adapted to colder climates than other crocodilians, such as the American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus), which does not make dwelling burrows and is restricted in the U.S. to the southern part of Florida.

• Protection against Fires – Burrows protect their occupants against a common environmental hazard in the southeastern U.S., fire. This is an advantage of alligator burrows that I did not appreciate until only a few days ago while in the field on St. Catherines. Yesterday, the island manager (and long-time resident) of St. Catherines, Royce Hayes, took us to a spot where last July a fire raged through a mixed maritime forest-freshwater wetland that also has numerous alligator burrows. The day after the fire ended, he saw two pairs of alligator tracks in the ash, meaning that these animals survived the fire by seeking shelter, and further reported that at least one of these trackways led from a burrow. The idea that these burrows can keep alligators safe from fires makes sense, similar to how gopher tortoises can live long lives in fire-dominated long-leaf pine ecosystems.

An area in the southern part of St. Catherines Island, scorched by a fire last July, that is also a freshwater wetland inhabited by alligators with burrows. The burrow entrances are all under water right now, which would work out fine for their alligator occupants if another fire went through there tomorrow. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island.)

An area in the southern part of St. Catherines Island, scorched by a fire last July, that is also a freshwater wetland inhabited by alligators with burrows. The burrow entrances are all under water right now, which would work out fine for their alligator occupants if another fire went through there tomorrow. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island.)

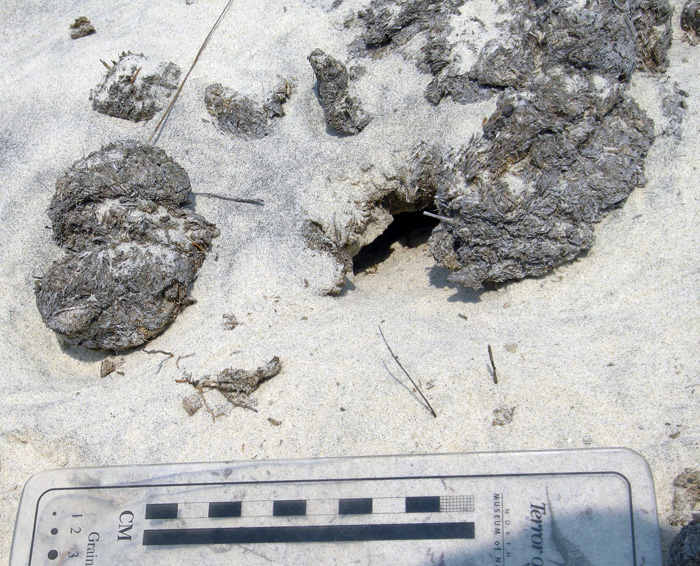

• Protection against Droughts – Burrows also probably help alligators keep their skins moist during droughts. Because these burrows often intersect the local water table, alligators might continue to use them as homes even when the accompany surface-water body has dried up. We saw several examples of such burrows during the past few days, some of which were occupied by alligators, even though their adjacent water bodies were nearly dry.

For example, yesterday Michael and I, while scouting a few low-lying areas for either occupied or abandoned dens, saw a small alligator – only about a meter (3.3 ft) long – in a dry ditch cutting through the middle of a pine forest. Curious about where alligator’s burrow might be, we approached it to see where it would go. It ran into a partially buried drainage pipe under a sandy road, a handy temporary refuge from potentially threatening bipeds. Seeing no other opening on that side of the road, we then checked the other side of the road, and were pleasantly surprised to find a burrow entrance with standing water in it. This small alligator had made the best of its perilously dry conditions by digging down to water below the ground surface.

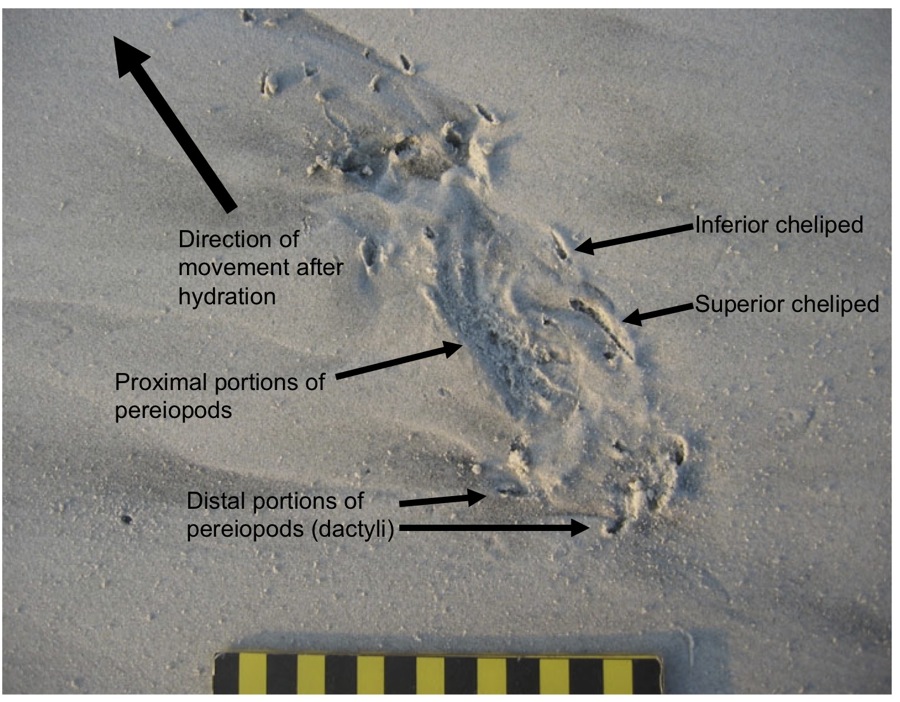

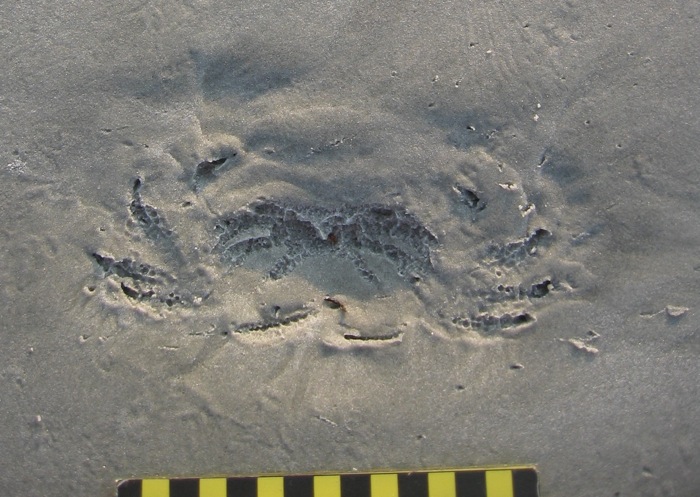

Alligator burrow (right) on the edge of a former water body. Notice how water is pooling in the front of the burrow, showing how it intersects the local water table. The entrance also had fresh alligator tracks and tail dragmarks at this entrance, showing that it was still occupied despite the lack of water outside of it. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Cumberland Island, Georgia.)

Alligator burrow (right) on the edge of a former water body. Notice how water is pooling in the front of the burrow, showing how it intersects the local water table. The entrance also had fresh alligator tracks and tail dragmarks at this entrance, showing that it was still occupied despite the lack of water outside of it. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Cumberland Island, Georgia.)

Alligator burrows (left foreground and middle background) in a maritime forest, also not associated with a wetland but marking the former location of one. Although the one to the left was unoccupied when we looked at it, it had standing water just below its entrance. This meant an alligator could have hung out in this burrow for a while after the wetland dried up, and it may have just recently departed. Also, once these burrows are high and dry, bones strewn about in front of them also add a delicious sense of dread. Here, Michael Page points at a deer pelvis, minus the rest of the deer. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Alligator burrows (left foreground and middle background) in a maritime forest, also not associated with a wetland but marking the former location of one. Although the one to the left was unoccupied when we looked at it, it had standing water just below its entrance. This meant an alligator could have hung out in this burrow for a while after the wetland dried up, and it may have just recently departed. Also, once these burrows are high and dry, bones strewn about in front of them also add a delicious sense of dread. Here, Michael Page points at a deer pelvis, minus the rest of the deer. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

What is especially interesting about the American alligator is how the only other species of modern alligator, A. sinensis in China, is also a fabulous burrower, digging long tunnels there too, which they use for similar purposes. This behavioral trait in two closely related but now geographically distant species implies a shared evolutionary heritage, in which burrowing provided an adaptive advantage for their ancestors.

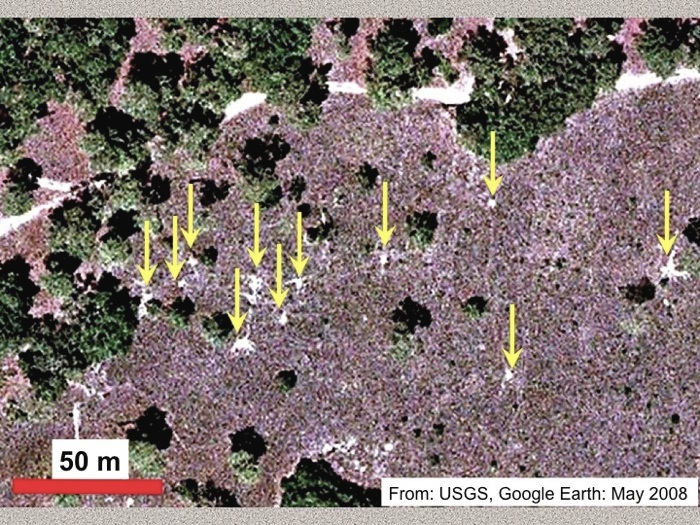

Thus like many research problems in science, we won’t really know much more about alligator burrows until we gather information about them, test some of the questions and other ideas that emerge from our study, and otherwise do more in-depth (pun intended) research. Nonetheless, our all-too-short trip to St. Catherines Island this week gave us a good start in our ambitions to apply a comprehensive approach to studying alligator burrows. Through a combination of ground-penetrating radar, geographic information systems, geology, and old-fashioned (but time-tested) field observations, we are confident that by the end of our study, we will have a better understanding of how burrows have helped alligators adapt to their environments since the Mesozoic.

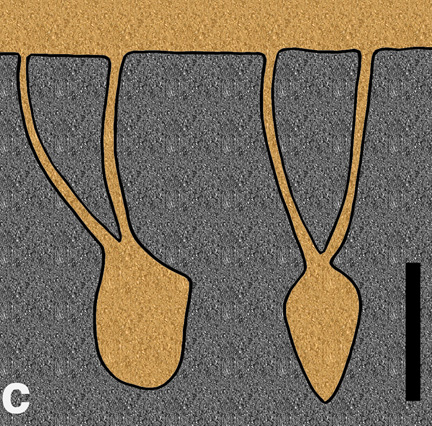

Juvenile alligators just outside two over-sized burrows, made and used by previous generations of older and much larger alligators. How might such burrows get preserved in the fossil record? How might we know whether these burrows were reused by younger members of the same species? Or, would we even recognize these as fossil burrows in the first place? All good questions, and all hopefully answerable by studying modern alligator burrows on the Georgia barrier islands. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

Juvenile alligators just outside two over-sized burrows, made and used by previous generations of older and much larger alligators. How might such burrows get preserved in the fossil record? How might we know whether these burrows were reused by younger members of the same species? Or, would we even recognize these as fossil burrows in the first place? All good questions, and all hopefully answerable by studying modern alligator burrows on the Georgia barrier islands. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

Further Reading

Erickson, G.M., et al. 2012. Insights into the ecology and evolutionary success of crocodilians revealed through bite-force and tooth-pressure experimentation. PLoS One, 7(3): doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031781.

Martin, A.J. 2009. Dinosaur burrows in the Otway Group (Albian) of Victoria, Australia and their relation to Cretaceous polar environments. Cretaceous Research, 30: 1223-1237.

Martin, A.J., Skaggs, S., Vance, R.K., and Greco, V. 2011. Ground-penetrating radar investigation of gopher-tortoise burrows: refining the characterization of modern vertebrate burrows and associated commensal traces. Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs, 43(5): 381.

St. John, J.A., et al., 2012. Sequencing three crocodilian genomes to illuminate the evolution of archosaurs and amniotes. Genome Biology, 13: 415.

Varricchio, D.J., Martin, A. J., and Katsura, Y. 2007. First trace and body fossil evidence of a burrowing, denning dinosaur. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B, 274: 1361-1368.

Waters, D.G. 2008. Crocodlians. In Jensen, J.B., Camp, C.D., Gibbons, W., and Elliott, M.J. (editors), Amphibians and Reptiles of Georgia. University of Georgia Press, Athens, Georgia: 271-274.

Acknowledgements: Much appreciation is extended to the St. Catherines Island Foundation, which supported our use of their facilities and vehicles on St. Catherines this week, and Royce Hayes, who enthusiastically shared his extensive knowledge of alligator burrows. I also would like to thank my present colleagues and future co-authors – Michael Page, Sheldon Skaggs, and Kelly Vance – for their valued contributions to this ongoing research: we make a great team. Lastly, I’m grateful to my wife Ruth Schowalter for her assistance both in the field and at home. She’s stared down many an alligator burrow with me on multiple islands of the Georgia coast, which says something about her spousal support for this ongoing research.