One of the more popular topics discussed nowadays by scientists and science writers via online social media and meetings regards how academic scientists – you know, those Ph.D. types who live in Ivory Towers – might most effectively conduct public outreach. Public outreach is also known as public engagement, or (my favorite) “engaged scholarship,” a term that stops just short of sheepishly admitting that most mainstream academic scholarship at universities is disengaged from the public. This allusion is connected to a consensus that academic scientists don’t do enough public outreach, causing people to nod their heads knowingly in agreement, even though this idea normally lacks, like, you know, actual data. (One exception is here, though.)

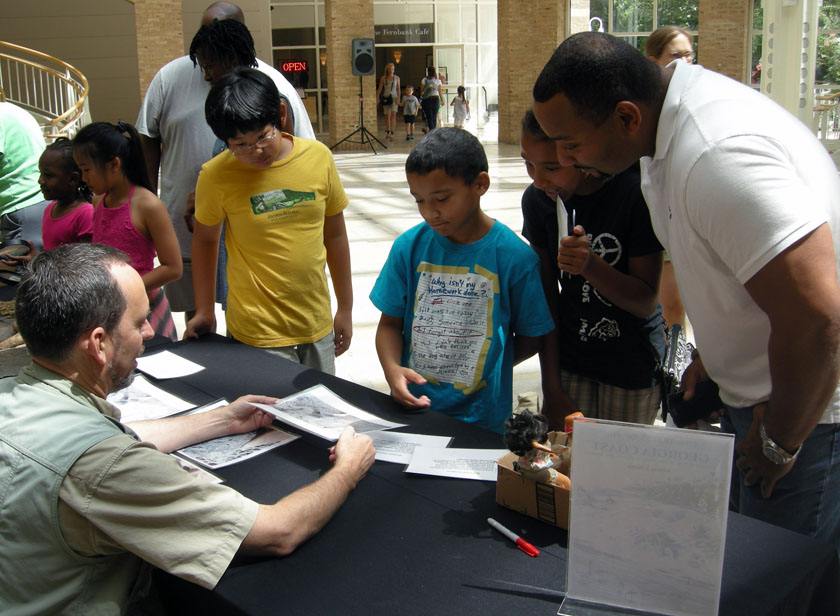

Wow, look a real paleontologist! Or maybe it’s a clever use of animatronics, or a holographic projection simulating a paleontologist, because everyone knows university scientists never go out to meet the public. (Photograph by Ruth Schowalter, taken at Fernbank Museum of Natural History in Atlanta, Georgia.)

Wow, look a real paleontologist! Or maybe it’s a clever use of animatronics, or a holographic projection simulating a paleontologist, because everyone knows university scientists never go out to meet the public. (Photograph by Ruth Schowalter, taken at Fernbank Museum of Natural History in Atlanta, Georgia.)

Regardless of whether academic scientists are disengaged, engaged, or simply eloping with people outside of their peer groups, at least part of the discussion revolves around how academics can be rewarded for their outreach. The conventional wisdom nowadays I read and hear about university scientists is that:

- They are terrible at communicating their science to laypeople, so everyone is better off if they just stay in their labs or in the field and not even try to talk with anyone other than their few (and I mean, very few) geeky friends.

- They will not be rewarded for doing outreach, unless it’s required by the granting agency that gave them whatever research grant they have at the time (grant blackmailing, you might say).

- They are actively discouraged from doing outreach, even if they’re already doing it through blogging, public presentations, making informative videos, working with science educators and science journalists, and so on.

With regard to the last of these, the negative consequence of outreach has been sometimes nicknamed the “Sagan Effect” (yes, that Sagan), in which non-outreaching scientists – arms crossed against their chests – may shun, poop-poo, or otherwise denigrate those scientists who dare to talk to the public. This basal primate behavior stems from the perception that scientists who are guilty of such slumming, including their writing books for non-colleagues, talking to journalists, and appearing on TV, must not be very good or very serious scientists (the latter being a far harsher judgement). And despite evidence to the contrary, this prejudice seemingly lingers.

Fortunately, my personal sense and one shared by many in the online science-loving community is that the tide has turned on this pernicious attitude. This shift is partly because most of those in academia who think “scientists who also try to be communicators = scum” are retiring, dying, or otherwise removing themselves from the meme pool, and their ranks are being filled incrementally by people who embrace public outreach. In other words, even ivory towers can evolve, especially if the next generation, schooled by people like Carl Sagan, pass on their memes.

Did you know that one of the best and most well-known science communicators – Bill Nye the Science Guy – does not have a Ph.D. in science and has never been a research scientist at a university? He “only” has a B.S. degree in mechanical engineering from Cornell University and some honorary degrees. Yet here he is, explaining natural selection (a basic principle of evolutionary theory) and connecting it to human alterations of environments, all while employing a masterfully mesmerizing blend of enthusiasm and ferocity that makes most of us Ph.D. types look like milquetoast. Or Wonder Bread. Or Miller Lite. Or some other grain-based metaphor that means really bland and boring. And he did it in less than two minutes. Oh, and did you know that one of his professors at Cornell was research scientist and science communicator Carl Sagan? That’s probably not a coincidence, just like the use of this video as an allegory for what’s happening to academic scientists in the U.S. right now.

Impediments also revolve around the discernment by scientists in the U.S. that most people may not be interested in what scientists have to say, regardless of what they have to say and how well they say it. I mean, when the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) has to put out an official statement denying the existence of mermaids, it’s going to be an uphill battle no matter how enthusiastic and knowledgeable a scientist might be. Incidentally, as an ichnologist, I can independently verify that NOAA is very likely correct: thus far, I have not seen a single mermaid trace on any Georgia beach or elsewhere in the world. Although that would make for a good April Fool’s post next year. (You’ve been warned.)

Actual photographic evidence of the existence of mermaids. In your face, NOAA! But what intrigues me here is the distinctive ichnological evidence resulting from the resting trace of a extant half-piscine-half-hominin tracemaker in a sandy intertidal environment, and how to assess the fossilization potential of such evidence. (Photograph originally from the documentary film Splash, with many copies available all over The Internets.)

Actual photographic evidence of the existence of mermaids. In your face, NOAA! But what intrigues me here is the distinctive ichnological evidence resulting from the resting trace of a extant half-piscine-half-hominin tracemaker in a sandy intertidal environment, and how to assess the fossilization potential of such evidence. (Photograph originally from the documentary film Splash, with many copies available all over The Internets.)

Related to this problem, though, is that the dream of young, academically trained scientists to become tenured research-oriented scientists in the U.S., who will then have little or no contact with people outside of their research group, is turning into a quaint anachronism. For one, anybody who has been following trends in U.S. universities knows that tenure-track positions in scientific fields are shrinking, especially as university budgets continue to tighten, salaries stagnate, and faculty support lessens. In other words, tenure-track positions are already alternative careers, not the norm.

This means that more people being trained as research scientists at those universities should expect to seek out or carve out their own careers in capacities other than those as traditional research scientists. One of these roles, of course, could be as scientists who communicate science to the public. Even so, scientists who wish to become science communicators with a public presence may not be rewarded for doing this in non-tenure-track positions at universities, or given enough time, as they will be teaching more classes and students. This means they may have to find other creative ways to channel their scientific knowledge while also earning a living wage. Not to mention health insurance, life insurance, retirement funds, and other mundane perks – ones we assumed that came with all of the hard work behind earning a Ph.D. in a scientific field – that are also in danger of diminishing in academia.

Wow, those are some broad-sweeping problems that require lots more discussion and some serious solutions! So what better way to do that than with personal anecdotes expressed through a blog and using my research specialty of ichnology? Stay tuned for that part tomorrow, Act I in Public Outreach via Ichnology, a mini-series based on a variety of real-life public-outreach encounters I’ve had as an academic paleontologist during the past week. And just to summarize what happened, while also foreshadowing: it was fun, real, and real fun.

How were these two photos of traces used to conduct public outreach of science with children at a natural history museum? If you want to find out, I guess you’ll have to read my next post.

How were these two photos of traces used to conduct public outreach of science with children at a natural history museum? If you want to find out, I guess you’ll have to read my next post.

Further Reading

Ecklund, E.H., James, S.A., and Lincoln, A.E. 2012. How academic biologists and physicists view science outreach. PLoS ONE, 7(5): e36240. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036240.

Mason, M.A. 2012. The Future of the Ph.D. Chronicle of Higher Education, May 12, 2012.