(This post is the second in a series discussing academic scientists and public outreach of their science, but with a focus on my recent experiences in using ichnology and paleontology for public outreach. The first of the series, introducing science outreach in general and some of its challenges for academic scientists, is here.)

One of the clichés of the environmentalism is to “think globally, act locally,” and the same principle applies well to public outreach done by scientists. For example, here in Atlanta, Georgia, I live near Fernbank Museum of Natural History. And by “near,” I mean I can ride my bicycle to it in 10-15 minutes from either home or my workplace at Emory University. Over my 20+ years in Atlanta, I’ve tried to cultivate a relationship with Fernbank, having done some informal consulting for them on exhibits, given public lectures about my research in ichnology and paleontology, shown some of my science-based artwork there, and otherwise done volunteer work that qualifies as public outreach.

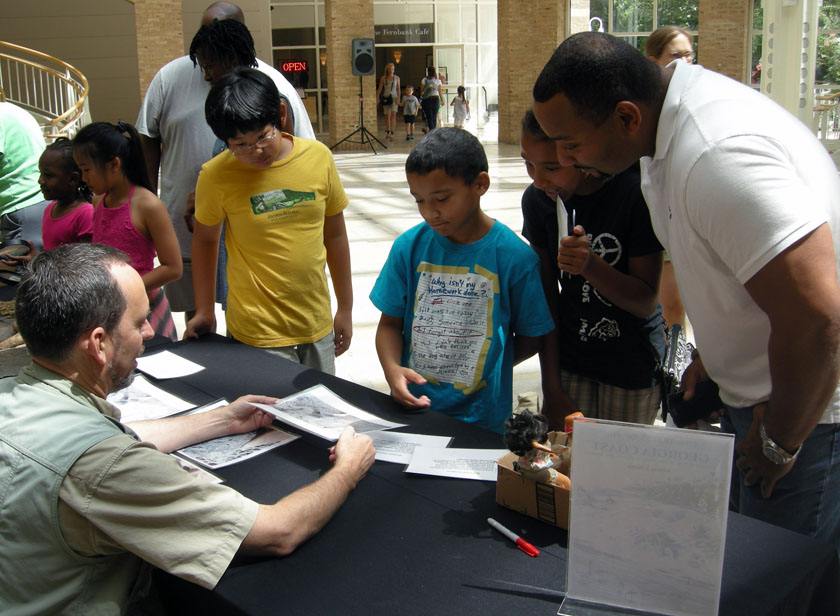

Look, a real paleontologist who somehow escaped from his “ivory tower” (or stone house) and found time to talk with the public! This is a small visual sample of the fun I had this past Saturday at Fernbank Museum of Natural History, talking with children and their parents about dinosaur trace fossils. Why yes, those are Paleontologist Barbies (one of them quite famous) sitting in the box to the right of me. Do you have a problem with that? (Photograph by Ruth Schowalter.)

Look, a real paleontologist who somehow escaped from his “ivory tower” (or stone house) and found time to talk with the public! This is a small visual sample of the fun I had this past Saturday at Fernbank Museum of Natural History, talking with children and their parents about dinosaur trace fossils. Why yes, those are Paleontologist Barbies (one of them quite famous) sitting in the box to the right of me. Do you have a problem with that? (Photograph by Ruth Schowalter.)

But one of my acknowledged deficiencies in public outreach with Fernbank and elsewhere has been sharing my science with kids. Full confession: I don’t have children. (As far as I know, that is. If I ever run for political office, I’ll find out for sure.) Moreover, nearly all of the students I teach are 18 to 22 years old, and I normally don’t have children around me through family, friends, or neighbors in everyday life. Thus most of my experience in communicating science at any level is with adults. This leaves me feeling a little handicapped and less confident about my abilities to adapt and use the unique set of skills needed for relating sometimes-complex scientific concepts to children.

Why should I bother getting bothered about this, especially in doing outeach with a local natural history museum? Well, a simple reality of natural history museums today is that their economic survival relies on children visiting them, and preferably (although not necessarily) with their parents in tow. Sure, educating the young has always been a role of natural history museums. But pitching science solely to kids while bypassing adults has become so pronounced in some museums that adults have begun complaining about the “infantilization” of museum exhibits.

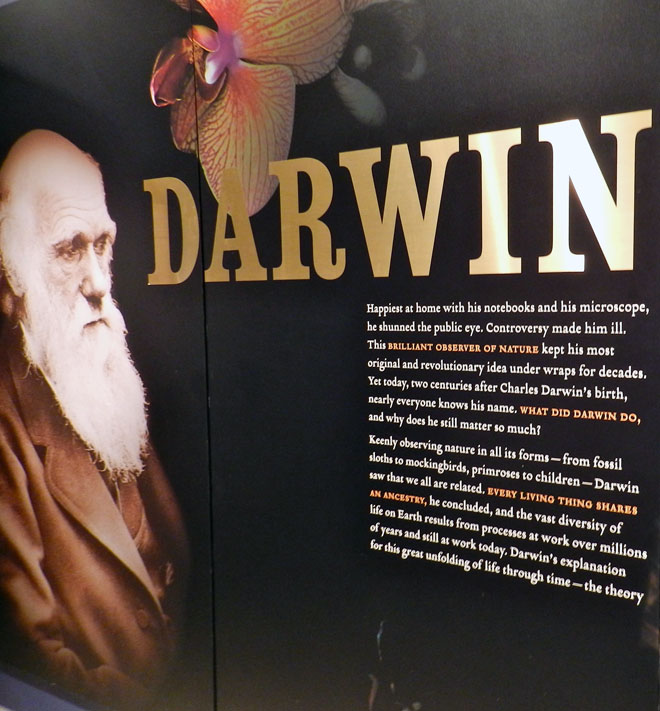

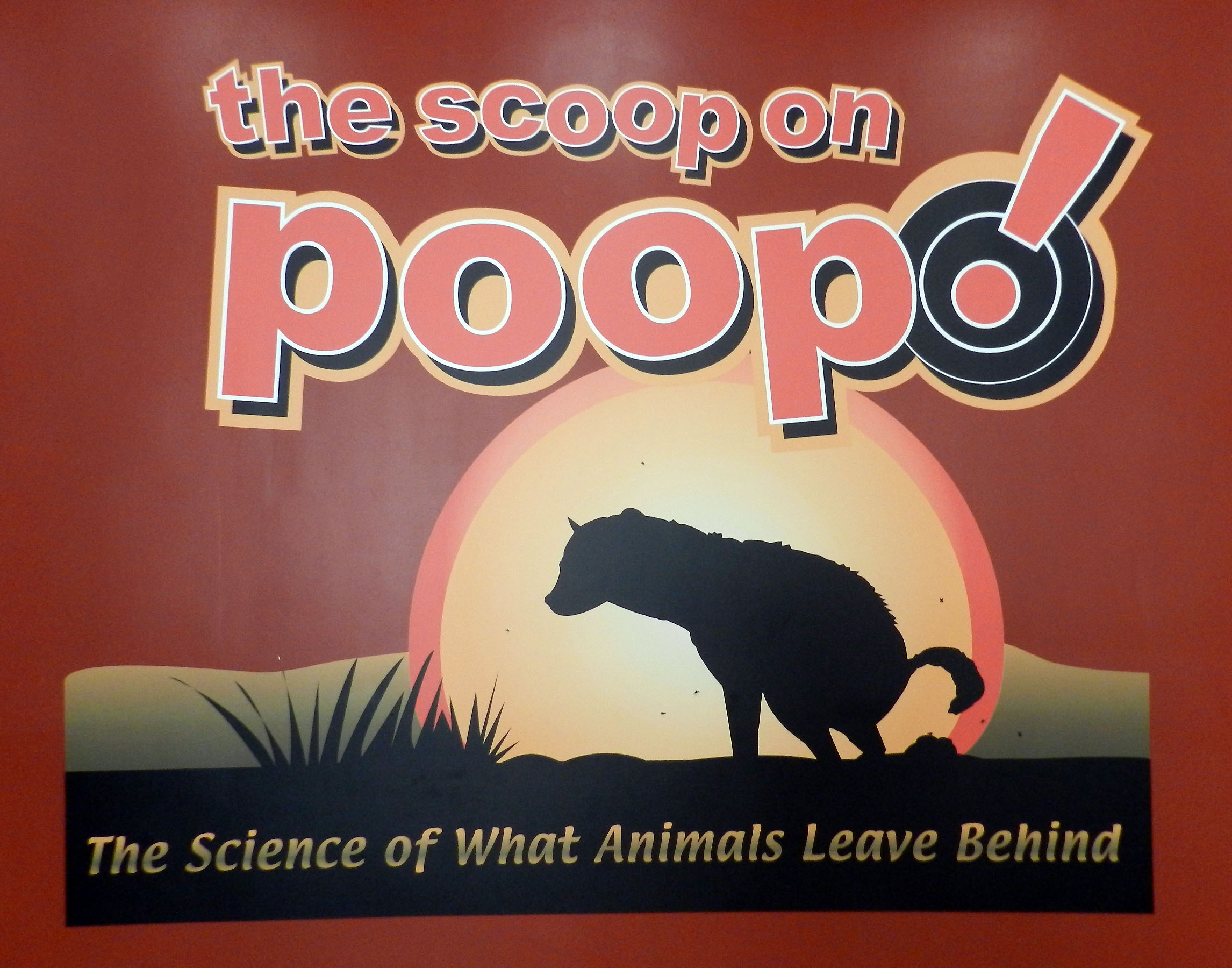

Fernbank is not immune to this charge. For example, the traveling exhibit they have there now – The Scoop on Poop – is clearly aimed at viewers 10 years old and younger, and is inspired by a children’s book with the same title. To be fair, though, Fernbank hosting the Darwin exhibit from the American Museum of Natural History last year was a refreshing concession to adults who certainly felt like kids, filled with excitement and awe, while learning about the roots of evolutionary theory.

A study in contrasts of traveling exhibits that have been to Fernbank Museum. Above, here’s part of the sign that greeted visitors to the Darwin exhibit, shown there September-December 2011…

A study in contrasts of traveling exhibits that have been to Fernbank Museum. Above, here’s part of the sign that greeted visitors to the Darwin exhibit, shown there September-December 2011…

…and here’s the sign welcoming people to the Scoop on Poop exhibit, showing there now. Gee, do you think each was intended for a different audience?

…and here’s the sign welcoming people to the Scoop on Poop exhibit, showing there now. Gee, do you think each was intended for a different audience?

So it was with a mixture of mild trepidation, but also eagerness, that I welcomed an opportunity for outreach with kids and their parents last Saturday, July 14. One of my friends who works at Fernbank asked me several weeks ago if I’d be interested in participating in a museum event they organized for July 14-15, called “The Scoop on Dinosaurs.” In this event, Fernbank put together a range of dinosaur- and other science-related activities and programs for kids, but of course also designed it with the assumption that these kids would be accompanied by parents or other adults. The problem was, all of the planned activities lacked a real, practicing scientist, let alone a paleontologist. And seeing that I’m one of the few paleontologists in the Atlanta area, I live close by, and I enjoy doing public outreach, it made sense for me to participate.

After discussing it with my Fernbank friend, we decided that a simple “meet the paleontologist” format would work best, with me sitting at a table and talking informally with people about one of my research topics – dinosaur trace fossils – as they dropped by. I also thought it would be good to have a few props, and ones that would provoke inquiry-based learning, or what educators used to call “thinking.”

For example, I brought with me two sets of dinosaur bones, one of which was noticeably denser than the other. (And by the way, real bones are essential, so the kids could say and remember when they held real dinosaur bones.) These differences, which engaged a sense other than sight, lent well to the question, “Why is one bone heavier than the other, even though they’re the same size?,” followed by a discussion of the preservation of dinosaur bones.

Whoa, dinosaur bones! The darker dinosaur bone on the left is noticeably heavier than the lighter-colored one on the right, which the kids could feel for themselves right away when they put one in each hand. After they noticed this, I asked them why, and next thing you knew, we were having a scientific discussion.

Whoa, dinosaur bones! The darker dinosaur bone on the left is noticeably heavier than the lighter-colored one on the right, which the kids could feel for themselves right away when they put one in each hand. After they noticed this, I asked them why, and next thing you knew, we were having a scientific discussion.

Of course, because I’m ichnologist, you just knew some traces and trace fossils were somehow going to be involved in this, too. Sure enough, my friends at Fernbank printed out and laminated the following two photographs of mine, which I used to introduce the concept of dinosaur tracks to the kids. But rather than just blabbing on about each track, I showed them the photos and asked “Which one is the dinosaur track, which one is the bird track?” One track was from a modern sandhill crane (Grus canadensis) made on a Georgia barrier island, whereas the other was from a non-avian Cretaceous theropod dinosaur.

Which is the bird track and which is the dinosaur track? It’s kind of a trick question, but one that also introduces the concept that questions can have multiple right answers, and those answers lead to more questions and deeper meaning. And just in case you were wondering, the track on the left is from a theropod dinosaur, preserved in Early Cretaceous rocks that are about 105 million years old, and the one on the right is from a modern sandhill crane. (Both photographs by Anthony Martin, the left one taken in Victoria, Australia, and right one taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Which is the bird track and which is the dinosaur track? It’s kind of a trick question, but one that also introduces the concept that questions can have multiple right answers, and those answers lead to more questions and deeper meaning. And just in case you were wondering, the track on the left is from a theropod dinosaur, preserved in Early Cretaceous rocks that are about 105 million years old, and the one on the right is from a modern sandhill crane. (Both photographs by Anthony Martin, the left one taken in Victoria, Australia, and right one taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

For the more shy kids, I asked them to just point to the one they thought was the dinosaur track, and assured them that it was OK to be wrong, because being wrong is also part of science. So what was fun about this exercise was how they could be right no matter which they picked. If they pointed to dinosaur track, I would tell them they were right. But if they instead pointed to the modern sandhill crane track, I smiled and said, “You’re right, but it’s from a modern dinosaur, because birds are dinosaurs, too.”

This revelation led to a short explanation of how some dinosaurs are still around as birds, even if all of the other dinosaurs went extinct 65 million years ago. (Most of the kids already knew this, but I’m not so sure all of their parents did.) They also could clearly see that the tracks, which were very similar in size and shape, comprised one piece of evidence showing the relatedness of these two animals, even though they were separated by more than 100 million years. With a few of the older kids, we even talked some about how they were able to distinguish the fossil track from the modern one. (“That looks like a rock, and that looks like sand,” some of them said. Couldn’t have said it better myself.) What was really fun about this approach was to see how much the kids’ parents learned from this ichnologically based exercise, too. In other words, this wasn’t just done with children in mind.

Another simple trace-fossil-oriented quiz came from a photo of a 75-million-year-old dinosaur coprolite. Only I didn’t tell them it was a coprolite; instead, I told them what was in it (bits and pieces of plants), that my hand was in the picture (showing the size of the rock), and that the rock was a type of dinosaur trace fossil.

What’s this? It has bits and pieces of plants in it, it’s big (there’s my hand for scale), and it came from a dinosaur. If you said “paleo-puke,” that’s not bad, but you’re thinking of the wrong end of the dinosaur. It’s a coprolite, probably from a hadrosaur (like Maisaura), and is from the Late Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of northwestern Montana.

What’s this? It has bits and pieces of plants in it, it’s big (there’s my hand for scale), and it came from a dinosaur. If you said “paleo-puke,” that’s not bad, but you’re thinking of the wrong end of the dinosaur. It’s a coprolite, probably from a hadrosaur (like Maisaura), and is from the Late Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of northwestern Montana.

With just those few clues, sometimes aided by my holding my nose, some kids actually figured it out (“DINOSAUR POOP!”), and even those who didn’t immediately get it were delighted with their answer after guiding them with just a few more questions. There’s probably something about their having recently learned proper toilet habits (reinforced daily) that makes feces loom large in a child’s imagination. So linking such traces to dinosaurs makes those feces even bigger, smellier, and hence more memorable.

With regard to other academic paleontologists who do public outreach, several parents mentioned that their kids regularly watch the TV show Dinosaur Train on PBS, and that’s how their children were learning about paleontology (or, more narrowly, just dinosaurs and pterosaurs). Although I’ve only seen a few clips from this show, I knew its host is also a real, academically trained research paleontologist with a Ph.D., Dr. Scott Sampson, sometimes known simply by the kids as “Dr. Scott.” So I made sure to tell these parents how fantastic it was to see an academic paleontologist with such credentials teaching paleontology in a children’s show. In other words, I was trying to counter the “Sagan effect,” while helping to dissuade parents from the notion that academic scientists are all disengaged from the public. (Maybe we paleontologists could call it the “Sampson effect.”)

Dr. Scott Sampson, an academic paleontologist who went on to do something a little different in his career, which was to become a science communicator with a recent focus on teaching paleontology to kids. Yet he still does peer-reviewed research on dinosaurs, meaning the two are not mutually exclusive. And you know what? The rest of us academic paleontologists think that’s cool.

Of course, I had lots of kids say, “I want to be a paleontologist!” Not wanting to crush their dreams with tales of pessimistic woe from academia (see my previous post if you need a big downer on that), I instead saw this as a chance for them to learn science in upcoming years, regardless of whether they become paleontologists or not. So advice I gave to those kids included (in particular order):

- Get outside as much as possible. Although I’m not an overly fervent acolyte of Richard Louv and his “get kids in nature” movement, I do agree with the basic premise that kids need to connect more directly with nature by simply getting their little butts outside. From what I understand, “Dr. Scott” preaches the same message, so it’s good for kids to hear this coming from paleontologists, who do lots of their best work outside.

- When you’re not outside, read as much as possible. Although, now that I think about it, I should have advised them to read outside.

- Take lots of math classes. These kids represent the future, and the future of paleontology means more computer applications and more quantification of our data. So they can’t think about doing paleontology without also thinking about how math will be used in that science. Even though some kids wrinkled their tiny noses at me when I said “lots of math,” they got the message.

- Take lots of science classes. And for the science classes, I told them that they’d better take geology, but also biology and chemistry. (I’m not sure if I mentioned physics, but maybe that was my way of getting back at fictional physicist Sheldon Cooper for what he’s said about geology.)

Yes, I know, all of this sounds wonderful, in a self-congratulatory, back-patting sort of way. Yay me! Nonetheless, while doing this outreach, I remained conscious of how I also fulfill a tenacious stereotype in paleontology. This typecasting has been discussed by fellow paleo-bloggers Victoria Arbour (here) and Brian Switek, the latter dubbing it the “male and pale” syndrome. It’s a syndrome exemplified by documentary filmmakers who pretend that the entire paleontological community is composed of middle-aged men of European descent, or, to throw in some diversity, older men of European descent.

Considering I live in an ethnically diverse place – Atlanta is more than 50% African-American, for starters – I’m reminded daily that my face doesn’t match those of most kids around me (and it’s not just the beard). This was certainly true for those kids and parents who stopped by to see me on Saturday: it was a rainbow of ethnicities totally unlike anything I experienced as a kid growing up in Indiana in the 1960s. But for here in Atlanta and many major metropolitan areas in the U.S. and around the world, this is normal. So if paleontologists who look like me plan to do public outreach, they have to be mindful of this reality, get educated about other ethnicities, and adjust accordingly. In this respect, I’ve been enlightened through working some with Emory’s Center for Science Education, which has had great success in implementing a variety of programs working to increase minority participation at all levels in STEM (science, technology, engineering, math) in the Atlanta area.

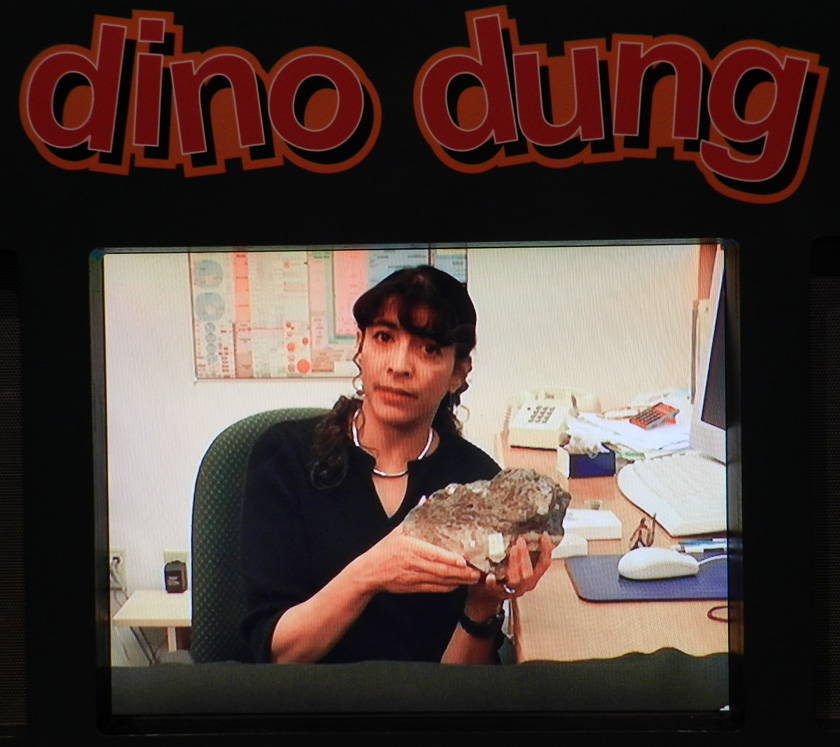

I’m also sensitive to the gender gap in perceptions of paleontologists, or the expectation that all paleontologists will be male, even as the demographics in our profession start to approach equity (though admittedly, we still have a long ways to go). So I made sure, after showing them the photo I had taken of a dinosaur coprolite from Montana and discussing how feces get fossilized, to tell them that the paleontologist who actually studied those coprolites was Dr. Karen Chin. Plus, I pointed toward the nearby Scoop on Poop exhibit and said they should go in there and watch Dr. Chin speak about her research on coprolites in several videos there. (Karen, if you’re reading this, thanks for your virtual help in being a cool role model!)

Dr. Karen Chin, the acknowledged world expert on dinosaur coprolites, who also doesn’t look like me (and that’s a good thing for both of us.) Here she is holding up one of her research subjects, which fortunately is sufficiently fossilized for her to gesture without getting any of it on her or the person behind the camera. Oh, and sorry if my photo taken from a video in The Scoop on Poop exhibit violates some sort of copyright, but I did it for the children. So there.

Dr. Karen Chin, the acknowledged world expert on dinosaur coprolites, who also doesn’t look like me (and that’s a good thing for both of us.) Here she is holding up one of her research subjects, which fortunately is sufficiently fossilized for her to gesture without getting any of it on her or the person behind the camera. Oh, and sorry if my photo taken from a video in The Scoop on Poop exhibit violates some sort of copyright, but I did it for the children. So there.

So it was with great joy and satisfaction that I’ll note my mere two hours of public outreach filled me with hope for the future. Many kids, accompanied by proud parents, stopped by to meet a “real paleontologist” and chat about, well, paleontology. Although I should have taken data, tabulated results, and analyzed them for significance, of the kids who said, “I want to be a paleontologist,” I recall the gender ratios were about 50:50. Probably my favorite brother-sister pair consisted of the brother who wants to be a paleontologist and the sister wants to be a marine biologist. (Making it even better, their dad was very pleased with the prospect of having two scientists in the family.)

I was also occasionally astonished at how knowledgeable some of the kids were. For example, one 10-year-old girl asked me whether one of the dinosaur bones I had brought was from a hadrosaurine or lambeosaurine dinosaur, which we then discussed (based on the extremely scanty evidence, that is). Her mother wore a face-splitting grin as she watched this exchange between her daughter and me, and other kids stood by in awe: looking at the girl, not me. Now that’s peer teaching!

Her (left): “What? You really think the phylogenetic distinction between the hadrosaur clades is based on THAT plesiomorphy?” Her sister (right): “Yeah, who taught you cladistics anyway?” Me: “Um, uh, OK. Say, have either of you ever watched Dinosaur Train?”

Her (left): “What? You really think the phylogenetic distinction between the hadrosaur clades is based on THAT plesiomorphy?” Her sister (right): “Yeah, who taught you cladistics anyway?” Me: “Um, uh, OK. Say, have either of you ever watched Dinosaur Train?”

Will I do this kind of public outreach again? Sure, and Fernbank can certainly count on me doing more such programs with them in the future. From this experience I also learned that “dinosaurs and kids” as a frame for science education, whether at natural history museums or elsewhere, is a fountain that apparently never goes dry. But even better, I can still use my academic research specialty – ichnology – to provide a different perspective on dinosaurs specifically and science in general, for children and parents alike.

Public outreach in paleontology with kids can be fun and rewarding, given the right setting, preparation, and attitude. Meanwhile, just behind me, Gigantosaurus is apparently chasing Argentinosaurus, giving a whole new twist to the term “ankle biter.” (Photograph by Ruth Schowalter, taken at Fernbank Museum in Atlanta, Georgia.)

Public outreach in paleontology with kids can be fun and rewarding, given the right setting, preparation, and attitude. Meanwhile, just behind me, Gigantosaurus is apparently chasing Argentinosaurus, giving a whole new twist to the term “ankle biter.” (Photograph by Ruth Schowalter, taken at Fernbank Museum in Atlanta, Georgia.)

Further Reading

None for now. Go outside instead.