How might the traces of animal behavior influence and lead to changes in the behavior of other animals, or even help other animals? The sands and the muds of the Georgia barrier islands answer this, offering lessons in how seemingly inert tracks, trails, burrows, and other traces can sway decisions, impinging on individual lives and entire ecosystems, and encourage seemingly unlikely partnerships in those ecosystems. Along those lines, we will learn about how the traces made by laughing gulls (Larus altricilla) and knobbed whelks (Busycon carica) aided sanderlings (Calidris alba) in their search for food in the sandy beaches of Jekyll Island.

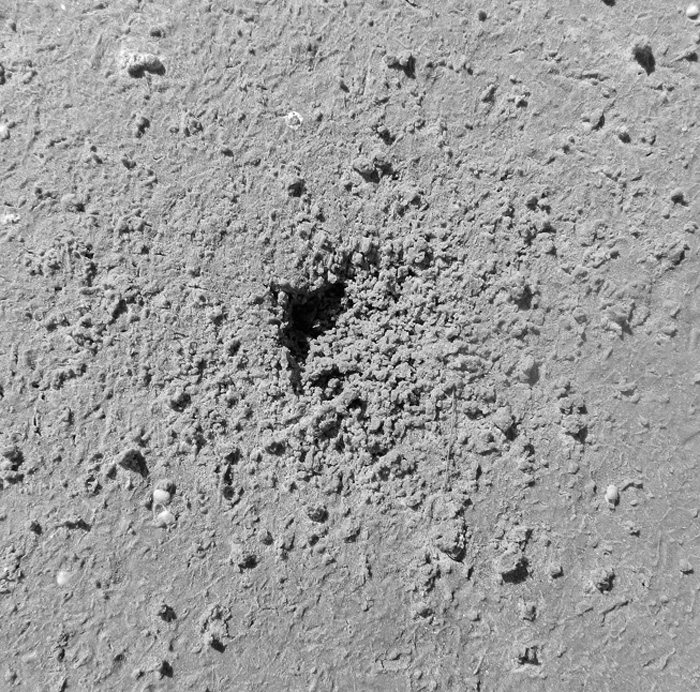

A roughly triangular depression in a beach sand on Jekyll Island, Georgia, blurred by hundreds of tracks and beak-probe marks of many small shorebirds, all of which were sanderlings (Calidris alba). What is the depression, how was it made, and how did it attract the attention of the sanderlings? Scale = size 8 ½ (men’s), which is about 15 cm (6 in) wide. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

A roughly triangular depression in a beach sand on Jekyll Island, Georgia, blurred by hundreds of tracks and beak-probe marks of many small shorebirds, all of which were sanderlings (Calidris alba). What is the depression, how was it made, and how did it attract the attention of the sanderlings? Scale = size 8 ½ (men’s), which is about 15 cm (6 in) wide. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Last week, we learned how knobbed whelks (Busycon carica), merely through their making trails and burrows in the sandy beaches of Jekyll Island, unwittingly led to the deaths of dwarf surf clams (Mulinia lateralis), the latter eaten by voracious sanderlings. Just to summarize, the dwarf surf clams preferentially burrowed around areas where whelks had disturbed the beach sand because the burrowing was easier. Yet instead of avoiding sanderling predation, the clustering of these clams around the whelks made it easier for these shorebirds to eat more of them in one sitting. Even better, this scenario, which was pieced together through tracks, burrows, and trails, was later verified by: catching whelks in the act of burying themselves; seeing clams burrow into the wakes of whelk trails; and watching sanderlings stop to mine these whelk-created motherlodes of molluscan goodness.

Before and after photos, showing how the burrowing of a knobbed whelk caused dwarf surf clams to burrow in the same small area (top), which in turn provided a feast for sanderlings (bottom); the latter is evident from the numerous tracks, peak-probe marks, and clam-shaped holes marking where these hapless bivalves formerly resided. (Both photographs by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

Before and after photos, showing how the burrowing of a knobbed whelk caused dwarf surf clams to burrow in the same small area (top), which in turn provided a feast for sanderlings (bottom); the latter is evident from the numerous tracks, peak-probe marks, and clam-shaped holes marking where these hapless bivalves formerly resided. (Both photographs by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

Was this the only trace-enhanced form of predation taking place on that beach? By no means, and it wasn’t even the only one involving whelks and their traces, as well as sanderlings getting a good meal from someone else’s traces. This is where a new character – the laughing gull (Larus altricilla) – and a cast of thousands represented by the small crustaceans – mostly amphipods – enter the picture. How these all come together through the life habits and traces these animals leave behind is yet another example of how the Georgia coast offers lessons in how the products of behavior are just as important as the behavior itself.

Considering that knobbed whelks are among the largest marine gastropods in the eastern U.S., it only makes sense that some larger animal would want to eat one whenever it washes up onto a beach. For example, seagulls, which don’t need much encouragement to eat anything, have knobbed whelks on their lengthy menus.

So when a gull flying over a beach sees a whelk doing a poor job of playing “hide-and-seek” during low tide, it will land, walk up to the whelk, and pull it out of its resting spot. From there, the gull will either consume the whelk on the spot, fly away with it to eat elsewhere (“take-out”), or reject it, leaving it high and dry next to its resting trace. An additional trace caused by gull predation might be formed when gulls carry the whelk through the air, drop them onto hard surfaces – such as a firmly packed beach sand – which effectively cracks open their shells and reveals their yummy interiors.

Paired gull tracks in front of a knobbed whelk resting trace, with the whelk tracemaker at the bottom of the photo. Based on size and form, these tracks were made by laughing gulls (Larus altricilla). The one on the left is likely the one that plucked the whelk from its resting trace, as its feet were perfectly positioned to pick up the narrow end of the whelk with its beak. The second gull might have seen what the first was doing and arrived on the scene soon afterwards, hoping to steal this potential meal for itself. For some reason, though, neither one ate it; instead, they discarded their object of desire there on the sandflat. For those of you who wondered if I then just walked away after taking the photo, I assure you that I threw the whelk back into water. At the same time, though, I acknowledged that the same sort of predation and rejection might happen again to that whelk with the next tidal cycle. Other shorebird tracks in the photo are from willets and sanderlings. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island.)

Paired gull tracks in front of a knobbed whelk resting trace, with the whelk tracemaker at the bottom of the photo. Based on size and form, these tracks were made by laughing gulls (Larus altricilla). The one on the left is likely the one that plucked the whelk from its resting trace, as its feet were perfectly positioned to pick up the narrow end of the whelk with its beak. The second gull might have seen what the first was doing and arrived on the scene soon afterwards, hoping to steal this potential meal for itself. For some reason, though, neither one ate it; instead, they discarded their object of desire there on the sandflat. For those of you who wondered if I then just walked away after taking the photo, I assure you that I threw the whelk back into water. At the same time, though, I acknowledged that the same sort of predation and rejection might happen again to that whelk with the next tidal cycle. Other shorebird tracks in the photo are from willets and sanderlings. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island.)

Sure enough, on the same Jekyll Island beach where we saw the whelk-surf clam-sanderling interactions mentioned last week, and on the same day, my wife Ruth Schowalter and I noticed impressions where whelks had incompletely buried themselves at low tide, only to be pried out by laughing gulls. Although we did not actually witness gulls doing performing, we knew it had happened because their paired tracks were in front of triangular depressions, followed by more tracks with an occasional discarded (but still live) whelk bearing the same dimensions as the impression.

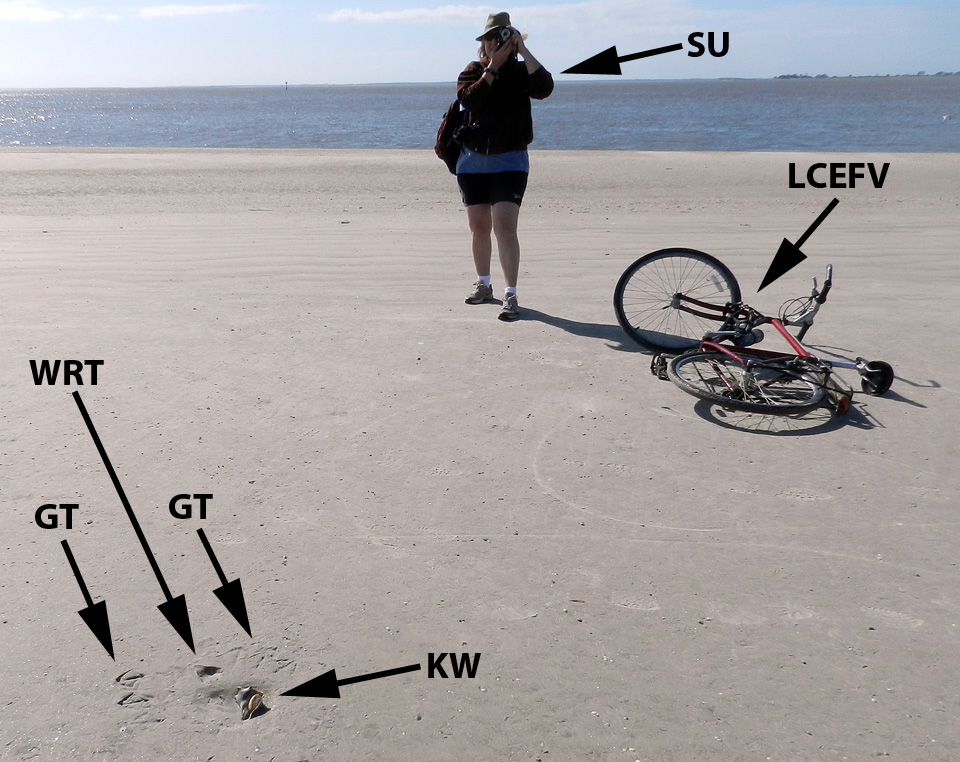

My wife Ruth aptly demonstrates how to document seagull and whelk traces (foreground) while on bicycle, no easy feat for anyone, but a cinch for her. Labels are: GT = gull tracks; WRT = whelk resting trace; KW = knobbed whelk; SU = spousal unit; and LCEFV = low-carbon-emission field vehicle. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

My wife Ruth aptly demonstrates how to document seagull and whelk traces (foreground) while on bicycle, no easy feat for anyone, but a cinch for her. Labels are: GT = gull tracks; WRT = whelk resting trace; KW = knobbed whelk; SU = spousal unit; and LCEFV = low-carbon-emission field vehicle. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island, Georgia.)

With this search image of a whelk resting trace in mind, we then figured out what had happened in a few places when we saw much more vaguely defined triangular impressions. These were also whelk resting traces, but they were nearly obliterated by sanderling tracks and beak marks; there was no sign of gulls having been there, nor any whelk bodies. Hence these must have been instances of where the gulls flew away with their successfully acquired whelks to drop them and eat them somewhere else. But why did the sanderlings follow the gulls with the shorebird equivalent of having a big party in a small place?

Yeah, I did it: so what? A laughing gull, looking utterly guiltless, stands casually on a Jekyll Island beach, unaware of how its going after knobbed whelks also might be helping its little sanderling cousins find amphipods. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Yeah, I did it: so what? A laughing gull, looking utterly guiltless, stands casually on a Jekyll Island beach, unaware of how its going after knobbed whelks also might be helping its little sanderling cousins find amphipods. (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Although many people may not know this, when they walk hand-in-hand along a sandy Georgia beach, a shorebird smorgasbord lies under their feet in the form of small bivalves and crustaceans. The latter are mostly amphipods (“sand fleas”), which through sheer number of individuals can compose nearly 95% of the animals living in Georgia beach sands. Amphipods normally spend their time burrowing through beach sands and eating algae between sand grains or on their surfaces.

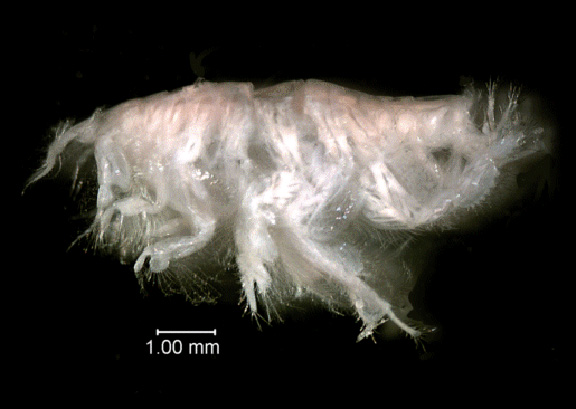

Close-up view of the amphipod Acanthohaustorius millsi, one of about six species of amphipods and billions of individuals living in the beach sands of the Georgia barrier islands, all of which are practically begging small shorebirds to eat them. Photo from here, borrowed from NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – a very good use of U.S. taxpayer money, thank you very much) and linked to a site about Gray’s Reef National Marine Sanctuary, which is about 30 km (18 mi) east of Sapelo Island, Georgia.

Close-up view of the amphipod Acanthohaustorius millsi, one of about six species of amphipods and billions of individuals living in the beach sands of the Georgia barrier islands, all of which are practically begging small shorebirds to eat them. Photo from here, borrowed from NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – a very good use of U.S. taxpayer money, thank you very much) and linked to a site about Gray’s Reef National Marine Sanctuary, which is about 30 km (18 mi) east of Sapelo Island, Georgia.

Because amphipods are exceedingly abundant and just below the beach surface, they represent a rich source of protein for small shorebirds. But if you really want to make it easier for these shorebirds to get at this food, just kick your feet as you walk down the beach. This will expose these crustaceans to see the light of day, and the shorebirds will snap them up as these little arthropods desperately try to burrow back into the sand. This, I think, is also what happened with the gulls pulling whelks off the beach surface. Through the seemingly simple, one-on-one predator-prey act of a gull picking up a whelk, it exposed enough amphipods to attract sanderlings, which then set off a predator-prey interaction between the sanderlings and amphipods, all centered on the resting trace of the whelk.

Two whelks near one another resulted in two resting traces, and now both are missing, which likely means they were taken by laughing gulls. Notice how all of the sanderling trampling and beak marks have erased any evidence of the gulls having been there. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island.)

Two whelks near one another resulted in two resting traces, and now both are missing, which likely means they were taken by laughing gulls. Notice how all of the sanderling trampling and beak marks have erased any evidence of the gulls having been there. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on Jekyll Island.)

So as a paleontologist, I always ask myself, how would this look if I found something similar in the fossil record, and how would I interpret it? What I might see would be a dense accumulation of small, overlapping three-toed tracks – with only a few clearly defined – and an otherwise irregular surface riddled by shallow holes. The triangular depression marking the former position by a large snail, obscured by hundreds of tracks and beak marks, might stay unnoticed, or if seen, could be disregarded as an errant scour mark. The large gull tracks would be gone, overprinted by the many tracks and beak marks of the smaller birds.

Take a look again at the scene shown in the first photograph, and imagine it fossilized. Could you piece together the entire story of what happened, even with what you now know from the modern examples? I’m sure that I couldn’t. Scale bar = 15 cm (6 in). (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Take a look again at the scene shown in the first photograph, and imagine it fossilized. Could you piece together the entire story of what happened, even with what you now know from the modern examples? I’m sure that I couldn’t. Scale bar = 15 cm (6 in). (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Hence the role of the instigator for this chain of events, the gull or its paleontological doppelganger, as well as its large prey item, would remain both unknown and unknowable. It’s a humbling thought, and exemplary of how geologist or paleontologist should stop to wonder how much they are missing when they recreate ancient worlds from what evidence is there.

Cast (reproduction) of a dense accumulation of small shorebird-like tracks from Late Triassic-Early Jurassic rocks (about 210 million years old) of Patagonia, Argentina. These tracks are probably not from birds, but from small bird-like dinosaurs, and they were formed along a lake shoreline, rather than a seashore. Nonetheless, the tracemaker behaviors may have been similar to those of modern shorebirds. Why were these animals there, and what were they eating? Can we ever know for sure about what other animals preceded them on this small patch of land, what these predecessors eating, and how their traces might have influenced the behavior of the trackmakers? (Photograph by Anthony Martin; cast on display at Museo de Paleontológica, Trelew, Argentina.)

Cast (reproduction) of a dense accumulation of small shorebird-like tracks from Late Triassic-Early Jurassic rocks (about 210 million years old) of Patagonia, Argentina. These tracks are probably not from birds, but from small bird-like dinosaurs, and they were formed along a lake shoreline, rather than a seashore. Nonetheless, the tracemaker behaviors may have been similar to those of modern shorebirds. Why were these animals there, and what were they eating? Can we ever know for sure about what other animals preceded them on this small patch of land, what these predecessors eating, and how their traces might have influenced the behavior of the trackmakers? (Photograph by Anthony Martin; cast on display at Museo de Paleontológica, Trelew, Argentina.)

Another parting lesson that came out of these bits of ichnological musings is that all of the observations and ideas in this week’s and last week’s posts blossomed from one morning’s bicycle ride on a Georgia-coast beach. Even more noteworthy, these interpretations of natural history were made on an island that some scientists might write off as “too developed” to study, its biota and their ecological relationships somehow sullied or tainted by a constantly abundant and nearby human presence. So whenever you are on a Georgia barrier island, just take a look at the life traces around you, whether you are the only person on that island or one of thousands, and prepare to be awed.

Further Reading

Croker, R.A. 1968. Distribution and abundance of some intertidal sand beach amphipods accompanying the passage of two hurricanes. Chesapeake Science, 9: 157-162.

Elbroch, M., and Marks, E. 2001. Bird Tracks and Sign of North America. Stackpole Books. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: 456 p.

Grant, J. 1981. A bioenergetic model of shorebird predation on infaunal amphipods. Oikos, 37: 53-62.

Melchor, R. N., S. de Valais, and J. F. Genise. 2002. The oldest bird-like fossil footprints. Nature, 417:936–938.

Wilson, J. 2011. Common Birds of Coastal Georgia. University of Georgia Press, Athens, Georgia: 219 p.