Writing about a place, its environments, and the plants and animals of those environments is challenging enough in itself. Yet to write about that place and what lives there, but without actually being there, seems almost like a type of fraud. Sure, given a specific place, I could read everything ever published about it, watch documentaries or other videos about it, carefully study 3-D computer-rendered images of its landscapes, interview people who have spent much time there, and otherwise gather information vicariously, all without experiencing it directly. But then is my writing just about the shadows on the wall of the cave?

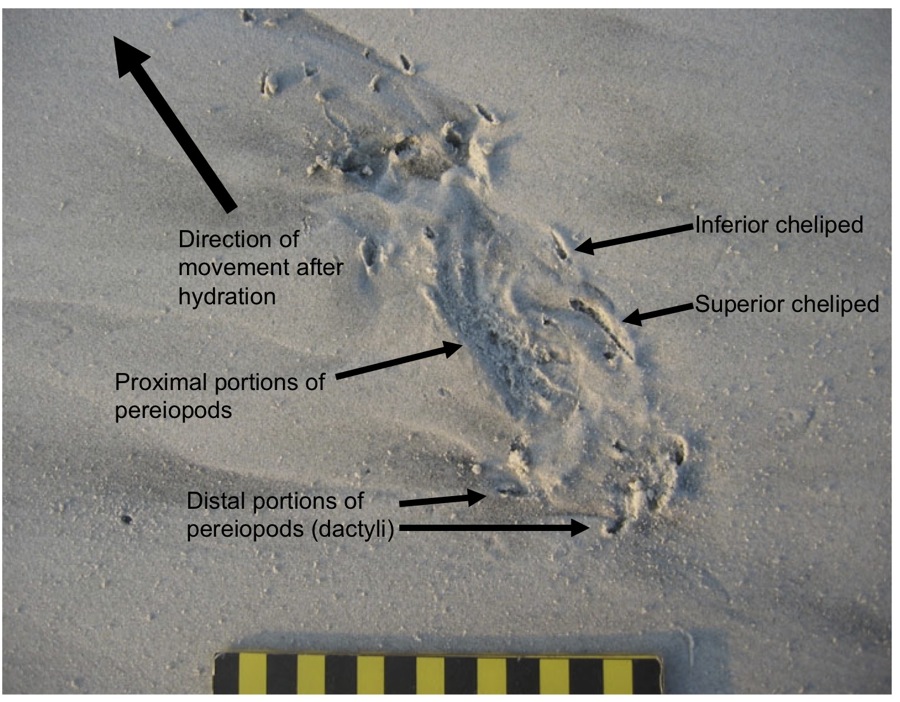

What do you see in this photo? I see fine quartz and heavy-mineral sand, originally parts of much larger rocks and forming parts of the Appalachian Mountains. I see the sand blowing down a long beach, but pausing to form ripples. I see a river otter galloping alongside the surf, slowing to a lope, then a trot, then back to a lope and a gallop. I see a brief rain shower, only about two hours after the otter has left the beach. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

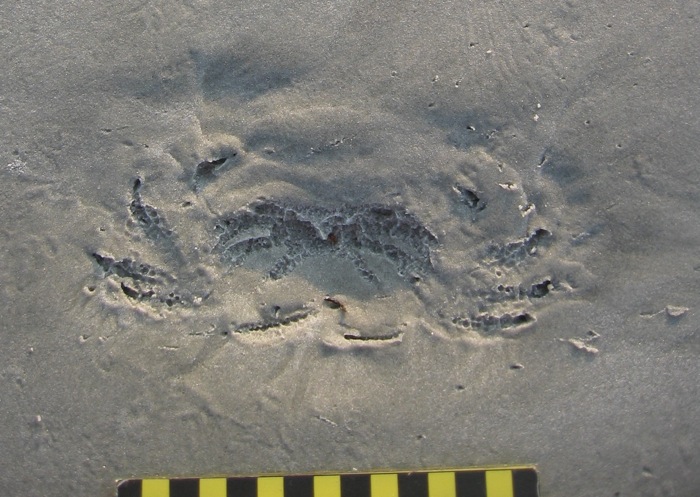

What do you see in this photo? I see fine quartz and heavy-mineral sand, originally parts of much larger rocks and forming parts of the Appalachian Mountains. I see the sand blowing down a long beach, but pausing to form ripples. I see a river otter galloping alongside the surf, slowing to a lope, then a trot, then back to a lope and a gallop. I see a brief rain shower, only about two hours after the otter has left the beach. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

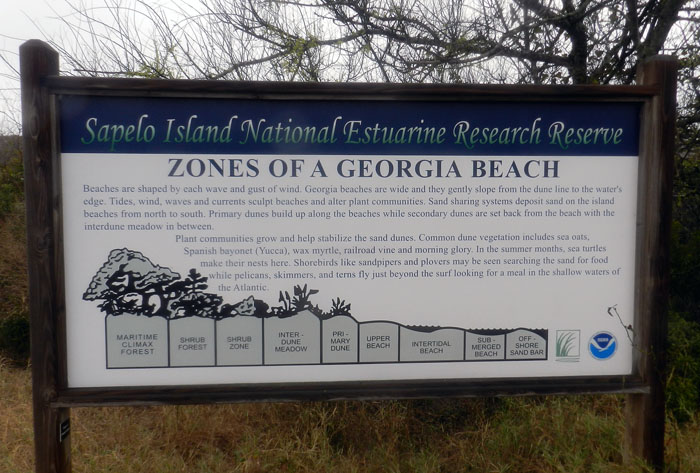

This pondering, of course, brings us to river otters. Yesterday, while on the third of a four-day writing retreat to Sapelo Island on the Georgia coast, my wife Ruth and I spent nearly an hour tracking a river otter along a long stretch of beach there. Had I read about river otters and their tracks before then? Yes. Had I watched video footage of river otters? Yes. Had I written about river otters and their tracks before then? Yes. Had I seen and identified their tracks before then? Yes. Had I seen river otters in the wild for myself? Yes, yes, and yes.

But still, this was different. When I first spotted the tracks on the south end of a long stretch of Cabretta Beach on Sapelo, I thought they would be ordinary. Granted, finding otter tracks is always a joy, especially when I’ve seen them on stream banks in the middle of Atlanta, Georgia. (Seriously, folks: river otters live in the middle of Atlanta. How cool is that?) And because Sapelo only has a few humans and is relatively undeveloped, your chances of coming across otter tracks on one of the beaches there isn’t like winning a lottery. But still.

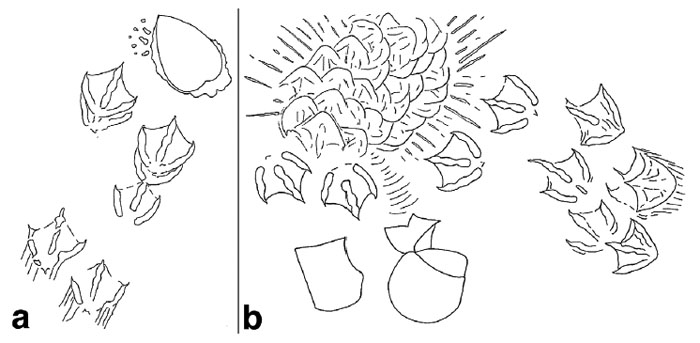

River otter (Lutra canadenis) tracks in what I (and some other trackers) call a “1-2-1” pattern. For gait, that translates into a “lope,” which is typical for an otter. In this pattern, one of the rear feet exceeds the front foot on one side, but the other rear foot ends up beside that same front foot; one front foot is behind. If that second rear foot lags behind the front foot, then it’s a “trot,” but if it exceeds the front foot (both rear feet ahead of both front feet), then that’s a “gallop.” Also, check out the wind ripples beneath the tracks, and raindrop impressions on top of them. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia; photo scale in centimeters, with the long bar = 10 cm (4 inches))

River otter (Lutra canadenis) tracks in what I (and some other trackers) call a “1-2-1” pattern. For gait, that translates into a “lope,” which is typical for an otter. In this pattern, one of the rear feet exceeds the front foot on one side, but the other rear foot ends up beside that same front foot; one front foot is behind. If that second rear foot lags behind the front foot, then it’s a “trot,” but if it exceeds the front foot (both rear feet ahead of both front feet), then that’s a “gallop.” Also, check out the wind ripples beneath the tracks, and raindrop impressions on top of them. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia; photo scale in centimeters, with the long bar = 10 cm (4 inches))

What made these tracks different was that they went on, and on, and on. These otter tracks spoke for the otter, saying in no uncertain terms that walking, trotting, loping, and galloping on a beach was the only thing it had on its schedule that morning. For nearly a kilometer (0.6 miles), we followed its tracks in the sandy strip of land between the high-tide line on the right and low coastal dunes on the left.

Follow the river otter tracks for as far as you can in this photo. Then, when you can’t see them any more, decide where it went. Does that sound like a challenge? It probably would be if you’ve only written about tracking otters, but it can be tough for experienced trackers, too. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

The tracks were only a few meters away from high tide, but sometimes turned that way, vanished, then reappeared further down the beach. This told us the otter was out close to peak tide that morning (between 6-8 a.m.) and was mixing up its exercise regime by occasionally dipping into the surf. Raindrop impressions on top of the tracks confirmed this, as the tracks looked crisp and fresh except for having been pitted by rain. For us, rain started inland and south of there on the island around 10 a.m., but reached the tracks sooner than that. We were there about three hours after then, so the otter was likely long gone, on to another adventure. Nonetheless, we made sure to look up and ahead frequently, just in case the trackmaker decided to come back to the scene of his or her handiwork.

For those of you who are intrigued by animal tracks (and why would you not be?), I suggest you try following those made by one animal, and follow it for as long as you can. That way you can learn much more about it as an individual animal, rather than just its species name. In my experience, after tracking an animal for a long time, nuances of its behavior, decisions, and even its personality emerge.

For example, this otter was mostly loping (its normal gait), but once in a while slowed to a walk or trot, or sped up, when it galloped. In short, the tracks showed enough variations to say that the otter was likely reacting to stimuli in its surroundings, and in many different ways. What gave it a reason to slow down? What impelled it to move faster? Why did it jump into the surf when it did, and why did it come out? Or, do otters just want to have fun?

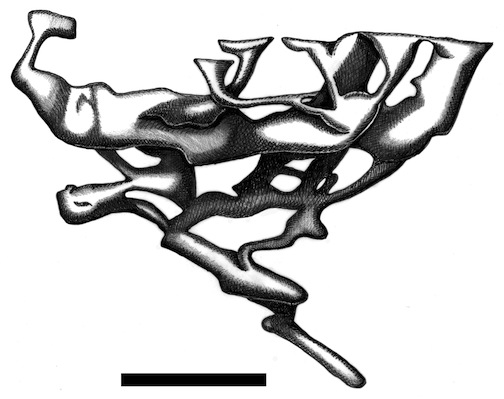

Gallop pattern for a river otter, in which both of its rear feet exceeded the front feet, making a group of four tracks. In this instance, the group defines a “Z” pattern when drawing a line from one track to another, but gallops sometimes also produce “C” patterns. Notice also how the groupings are separated by a space with no tracks. This is also diagnostic of a gallop pattern: the longer the space, the longer the “air time” for the animal, when it was suspended above the ground between when its feet touched the ground. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

Gallop pattern for a river otter, in which both of its rear feet exceeded the front feet, making a group of four tracks. In this instance, the group defines a “Z” pattern when drawing a line from one track to another, but gallops sometimes also produce “C” patterns. Notice also how the groupings are separated by a space with no tracks. This is also diagnostic of a gallop pattern: the longer the space, the longer the “air time” for the animal, when it was suspended above the ground between when its feet touched the ground. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

Now I realize that discerning a “personality” and “moods” of a non-human animal based on a series of its tracks might sound like a little too “woo-woo” and “New Agey” for my skeptical scientist friends to accept, followed by jokes about my becoming a pet psychic. As a fellow skeptical scientist, I’m totally OK with that. In fact, I will join them in making fun of people who try to tell us that, say, they know what a Sasquatch was thinking as it strolled through a forest while successfully avoiding all cameras and other means of physical detection.

But here’s what happens when you’ve tracked a lot (which I have) and made lots of mistakes while tracking, but later corrected them (ditto). Intuition kicks in, and it usually works. For instance, at one point in following this otter, I lost its tracks on a patch of hard-packed sand. (Granted, I should have gotten down on my hands and knees to look closer, but was being lazy. Hey, come on, I was on a writer’s retreat.) So I then asked myself, “Where would I (the otter) have gone?” and looked about 10 meters (30+ feet) ahead in what felt like the right place. There they were. This happened three more times, results that led me to conclude this was almost like some repeatable, testable, falsifiable science-like thing happening. So there.

OK, remember when I asked you to follow the river otter tracks for as far as you could in this photo, and when you couldn’t see them any more, decide where it went? If not, go back and re-read it and look at the photo again. If you have, then look at the red arrow, backtrack to the footprints in the foreground of the photo, then go forward. Do you see how the tracks are staying in the subtly lower area, just left of the slightly higher sand piled on the plant debris? Keep picking out those low areas, and you’ll end up where the arrow is pointing. After all, if I were an otter, that’s where I would go. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

OK, remember when I asked you to follow the river otter tracks for as far as you could in this photo, and when you couldn’t see them any more, decide where it went? If not, go back and re-read it and look at the photo again. If you have, then look at the red arrow, backtrack to the footprints in the foreground of the photo, then go forward. Do you see how the tracks are staying in the subtly lower area, just left of the slightly higher sand piled on the plant debris? Keep picking out those low areas, and you’ll end up where the arrow is pointing. After all, if I were an otter, that’s where I would go. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

Oh yeah, regarding my main topic sentence: What’s all this have to do with writing about a place? Well, because of that otter and its tracks, I now understand at least one otter much better than before, and feel like I can write with a little more authority about otters in general. You know, like what you just read.

Do you understand this river otter and its place a little better now, thanks to it leaving so many tracks while it enjoyed a morning at the beach, and because I tracked it for such a long time, and then wrote about that experience in that same place? Please say “yes,” as I want to keep writing about stuff like this. P.S. Thanks to Sapelo Island, this river otter, and my wife Ruth for teaching me so much yesterday. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)

Do you understand this river otter and its place a little better now, thanks to it leaving so many tracks while it enjoyed a morning at the beach, and because I tracked it for such a long time, and then wrote about that experience in that same place? Please say “yes,” as I want to keep writing about stuff like this. P.S. Thanks to Sapelo Island, this river otter, and my wife Ruth for teaching me so much yesterday. (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on Sapelo Island, Georgia.)