Life can certainly imitate art, as can life traces. I was reminded of this last week while doing field work on St. Catherines Island (Georgia), and after encountering traces made by two very different animals, alligators and fiddler crabs. What was unexpected about these traces, though, was how they intersected one another in a way that, for me, evoked scenes from the recent blockbuster summer movie, Pacific Rim.

Could these be the tracks of a kaiju, making landfall on the shores of Georgia? Sorry to disappoint you, but they’re just the right-side and very large tracks of an American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), accompanied by its tail drag-mark, left on a sandy area next to a salt marsh. Note the scale impressions in its rear-foot track, a symbol of the awesome reptilian awesomeness of its tracemaker. But wait: what nefarious nonsense is happening to the tail drag-mark, which is being covered by tiny balls of sand? Who made that hole next to the drag-mark? And what the heck was a raccoon (Procyon lotor) doing in the neighborhood, leaving its track on the tail drag-mark? With such a monster on the loose, shouldn’t that raccoon be hiding in the forest? (Photo by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island; scale in centimeters.)

For anyone who has not seen Pacific Rim, you can read what I wrote about its distinctive fictional ichnology here. But what came to my mind while I was doing field work was one of the themes expressed early on in the film: how quickly humanity returned to normalcy following a lull in attacks by gigantic monsters (kaiju) that emerged from the ocean, destroyed major cities, and killed millions of people. It reminded me of how horrific hurricanes can strike a coast, such as the 1893 Sea Islands Hurricane that hit Georgia, but because no hurricane like it has happened there since, coastal developers think it’s hunky-dory to start building on salt marshes.

But enough about malevolent evil as exemplified by kaiju and coastal developers: let’s get back to traces. Last week, I was on St. Catherines Island for a few days with my wife (Ruth) and an undergraduate student (Meredith) to do some field reconnaissance of my student’s proposed study area. The area was covered by storm-washover fans; these are wide, flat, lobe-shaped sandy deposits made by storm waves, which span from the shoreline to more inland on barrier islands. We were trying to find out what traces had been left on these fans – tracks, burrows, scrapings, feces, and so on – which would tell us more about the distribution and behaviors of animals living in and around the washover fans.

Part of a storm washover fan on St. Catherines Island (Georgia), with the sea to the left and salt marsh (with a patch of forest) in the background. Say, I wonder what made those tracks coming out of the tidal creek and toward the viewer? (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

Part of a storm washover fan on St. Catherines Island (Georgia), with the sea to the left and salt marsh (with a patch of forest) in the background. Say, I wonder what made those tracks coming out of the tidal creek and toward the viewer? (Photograph by Anthony Martin.)

It didn’t take long for us to get surprised. Within our first half hour of walking on a washover fan and looking at its traces, we found a trackway left by a huge alligator, split in half by a wavy tail-drag mark. I recognized this alligator from its tracks, as I had seen them in almost exactly the same place more than a year before. Besides their size, though, what was remarkable about these tracks was their closeness to a salt marsh behind the washover fan. When we looked closer, we could see long-established trails cutting through the salt-marsh vegetation, which were the width of a large adult alligator.

That ain’t no skink: the distinctive tracks and tail drag-mark of a large alligator, strolling through a storm-washover fan and next to a salt marsh. You think these animals are “freshwater only”? Traces disagree. Scale = 10 cm (4 in). (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

That ain’t no skink: the distinctive tracks and tail drag-mark of a large alligator, strolling through a storm-washover fan and next to a salt marsh. You think these animals are “freshwater only”? Traces disagree. Scale = 10 cm (4 in). (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Alligator trail cutting through a salt marsh. Trail width was about 45-50 cm (18-20 in), which is about twice as wide as a raccoon trail. And it wasn’t made by deer or feral hogs either, because, you know, alligators. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Alligator trail cutting through a salt marsh. Trail width was about 45-50 cm (18-20 in), which is about twice as wide as a raccoon trail. And it wasn’t made by deer or feral hogs either, because, you know, alligators. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

So although the conventional wisdom about alligators is that these are “freshwater-only” animals, their traces keep contradicting this assumption. Sure enough, in the next few days, we saw more alligator tracks of varying sizes going into and out of tidal creeks, salt marshes, and beaches.

Based on a few traits of these big tracks, such as their crisp outlines (including scale impressions), the alligator had probably walked through this place just after the tide had dropped, only a couple of hours before we got there. But when we looked closer at some of the tracks along the trackway, we were astonished to see that something other than the tides had started to erase them, causing these big footprints to get fuzzy and almost unrecognizable.

The culprits were sand fiddler crabs (Uca pugilator), which are exceedingly abundant at the edge of the storm-washover fans closest to the salt marshes. These crabs are industrious burrowers, making J-shaped burrows with circular outlines corresponding to their body widths. They also scrape the sandy surfaces outside of their burrows to eat algae in the sand, then roll up that sand into little balls, which they deposit on the surface.

In this instance, after this massive alligator had stomped through their neighborhood, they immediately got back to work: digging burrows, scraping the surface, and making sand balls. Within just a few hours, parts of the alligator trackway was obscured. If these parts had been seen in isolation, not connected to the clear tracks and tail drag mark, I doubt we would have identified these slight depressions as large archosaur tracks.

Hey, what’s going on here? Who would dare to erase and fill in giant alligator tracks? Don’t they know who they’re dealing with? (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Hey, what’s going on here? Who would dare to erase and fill in giant alligator tracks? Don’t they know who they’re dealing with? (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Going, going, gone: alligator tracks nearly obliterated by burrowing, surface scraping, and sand balls caused by feeding of sand fiddler crabs (Uca pugilator). (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia; scale in centimeters.)

Going, going, gone: alligator tracks nearly obliterated by burrowing, surface scraping, and sand balls caused by feeding of sand fiddler crabs (Uca pugilator). (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia; scale in centimeters.)

What was even neater, though, was how some of the fiddler crabs took advantage of homes newly created by this alligator. In at least a few tracks, we could see where fiddler crabs had taken over the holes caused by alligator claw marks. In other words, fiddler crabs saw these, said, “Hey, free hole!”, and moved in, not caring what made them.

Don’t believe me about fiddler crabs moving into alligator claw marks? OK, then what’s that I see poking out of that alligator claw mark (red square)? (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia; scale in centimeters.)

Don’t believe me about fiddler crabs moving into alligator claw marks? OK, then what’s that I see poking out of that alligator claw mark (red square)? (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia; scale in centimeters.)

Why, it’s a small sand fiddler crab! Does it care that its new home is an alligator claw mark? Nope. Does ichnology rule? Yup. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

Why, it’s a small sand fiddler crab! Does it care that its new home is an alligator claw mark? Nope. Does ichnology rule? Yup. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia.)

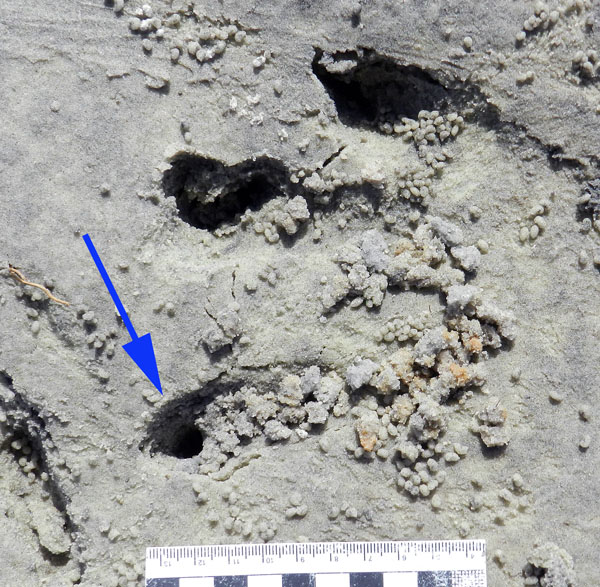

Need a free burrow? Then why start digging a new one when alligator claw marks (arrow) gives you a nice “starter burrow”? Notice the sculpted, round outline, showing the claw mark was modified by a crab. Also check out the sand balls left outside of the other claw marks, meaning these have probably been occupied and mined for food by fiddler crabs, too. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia; scale in centimeters.)

Need a free burrow? Then why start digging a new one when alligator claw marks (arrow) gives you a nice “starter burrow”? Notice the sculpted, round outline, showing the claw mark was modified by a crab. Also check out the sand balls left outside of the other claw marks, meaning these have probably been occupied and mined for food by fiddler crabs, too. (Photograph by Anthony Martin, taken on St. Catherines Island, Georgia; scale in centimeters.)

As a paleontologist, the main lesson learned from this modern example that can be applied to fossil tracks, is this: any tracks made in the same places as small, burrowing invertebrates – especially in intertidal areas – might have been destroyed or otherwise modified immediately by the burrowing and feeding activities of those much smaller animals. The secondary lesson is on how large vertebrate tracks can influence the behaviors of smaller invertebrates, resulting in their traces interacting and blending with one another.

More symbolically, though, these alligator tracks and their erasure by fiddler crabs also conjured thoughts of fictional and real analogues: Pacific Rim and coastal development, respectively. With regard to the latter, it felt too much like how, as soon as a hurricane (a meteorological “monster”) passes through a coastal area, we begin to talk about rebuilding in a way that, on the surface, wipes out all evidence that a hurricane ever happened.

Yet unlike fiddler crabs, we have memories, we have records – including the plotted “tracks” of hurricanes – and thanks to science, we can predict the arrival of future “monsters.” So the preceding little ichnological story also felt like a cautionary tale: pay attention to the tracks while they are still fresh, and be wary of those that vanish too quickly.